A facilitated learning analysis (FLA) with dozens of valuable lessons learned was just released about an incident where six firefighters were entrapped on a wildfire and had to run to safety through unburned vegetation. The incident within an incident occurred August 19, 2018 on the Mendocino Complex of Fires east of Ukiah, California. Six firefighters received burns and other injuries when the fire crossed a dozer line in multiple locations during burnout operations and cut them off from their planned egress. Some of the firefighters refused treatment, while others were transported to hospitals where they were treated and released.

You can download the entire report here: (large 7MB file).

One thing to keep in mind when you read the lessons learned is that the organizational structure on the fire, which ultimately burned more than 459,000 acres, was very unusual. Two complete Type 1 incident management teams were ordered for the fire due to its enormous size. Normally when there are two teams on a very large fire they divide it into two geographical zones, with each team assuming responsibility for one. Logistically, in this case, there were not enough logistical resources available to support two large incident command posts, so everyone worked out of one base. The two teams were merged into one, which produced duplicates in some overhead positions.

The report was very skillfully designed and written and could be a valuable resource for wildland firefighters.

Below we have a very brief summary from the report of the entrapment, and following that, all of the lessons learned attributed to the personnel who were on the fire, in their own words. We did not include another section from the report that contains analysis from the FLA team.

BRIEF SUMMARY FROM THE REPORT

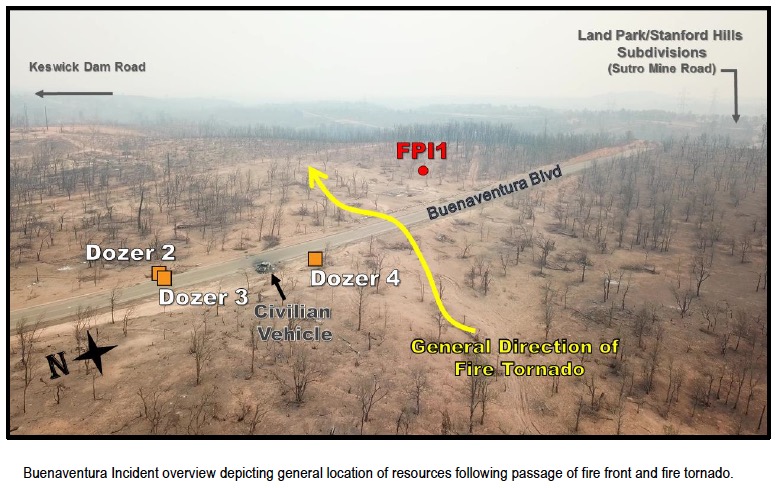

During burnout operations, a sudden wind shift and explosive fire growth happened and personnel were cut off from their escape routes. Most of the firefighters were able to move back to their vehicles to exit the area. However, six individuals farther down the dozer line were forced to run in front of the advancing flame front, through unburned fuels to a nearby dirt road for approximately one mile before they were picked up and transported for treatment. Five Los Angeles Fire Department firefighters and one CAL FIRE firefighter were injured. Two unoccupied CAL FIRE emergency crew transports parked in the vicinity sustained damage from the fire when it jumped containment lines.

LESSONS LEARNED BY THE PARTICIPANTS

Interviews were conducted with key personnel involved in the entrapment on the Ranch Fire. At the conclusion of each interview, each person was asked what they learned for themselves from this event and what they believe the greater wildland fire community could learn. The following are the subsequent lessons the participants shared with the FLA Team that they believe could benefit others. When possible, these lessons were written in the words of those interviewed, though a few places lesson were edited for clarity. These lessons were broken into four categories: Aviation, Inter- Crew, Fireline, and Overhead.

AVIATION

- I’m not sure what lessons I learned could apply to the ground. It is not my job to second guess what folks are doing on the ground. My job is to support them and give them our perspective to help them to succeed. They use our input as another tool.

- Let incoming aircraft know what type of response they are being requested. This is what it would sound like, “Declare an IWI and have them report to Mendo IP (initial point – aviation) for an IWI.”

- We had an awareness of not taking risks that would incur potential damage or injuries or add more complexity. There is a balance when you are dealing with a life threatening situation that we didn’t make things worse, i.e. compromise ourselves in poor visibility. We ordered additional support to maintain span of control. We immediately ordered up additional support and didn’t try to tackle it ourselves. Didn’t want to be a liability.

- Declare an IWI when injuries are discovered and follow IWI protocols so communication is clearer. Not declaring this an IWI created a lot of confusion because others did not understand the extent of the injuries or people involved.

- I knew the voice on the ground so I did not provide decision points or trigger points. I just gave him the facts based upon what he was seeing. If it was someone else, I might have said no to the operation (in reference to when Dep. Branch II was asking about location of the fire for the burnout operation).

INTER-CREW

- Everybody has a responsibility to run a risk management profile and use Crew Resource Management.

- Ask questions when something does not make sense to you.

- Ensure you and your resources are briefed thoroughly and information is flowing. People need to understand the assignment and have buy in.

- Maintain transparent communication between resources and within your crew.

- Speak your mind if something does not feel right. Make sure your voice is heard and understood when doing so. Validate subordinates concerns by passing them up the chain of command. If you are asked a question and don’t have an answer, re-evaluate.

- Trust but verify. You will receive intel from other resources, but validate that information for yourself. Gather your situational awareness.

- Rely on your experienced personnel within the group, no matter what position they hold.

- Do not let urgency influence your actions.

FIRELINE

- Remain vigilant and consider the worst-case scenario. Play the “What if?” in your mind.

- Take the time to assess the situation and determine if it fits an IWI circumstance. ”I was mad at myself for not following the IWI in the 206.”

- Good communications are critical. Validate the information you are given. Take time to scout the line. The best thing to do is ask questions for the things that are unknown and communicate with your people frequently.

- Have the courage to turn down an assignment.

- Vulnerability and approachability are key traits of a strong leader.

- There was a perception that refusing an assignment could get you less desirable jobs or reassigned on the fire.

- Rank adds to the confusion and tension around speaking up.

- I think the dysfunction and disconnect between commanders intent and what was happening in division and branches was a contributing factor to the very rushed firing operation.

- The CAL FIRE/Fed rivalry was evident on this fire and I believe it was a detriment to the operational tempo and production.

- Help your supervisors and use humble inquiry to have a discussion about tactics. Do things make sense? What is the end state?

- There was no good vantage point for the lookout. Our perception is that a lookout can see the fire but is maybe in a less than desirable location.

- If you don’t get a good briefing, ask for it. Make sure to receive a thorough briefing from supervisors.

- I think we need to encourage a culture of voicing concerns in a professional manner. Leadership needs to be approachable. I’ve been a metro firefighter for more than 30 years.

- I’ve only been in wildland for 6 years, and I’m like born again after doing some structure protection just a few weeks before on another fire (burning out around six homes, we saved five of them). I really believe in that – this highly influenced my decision to accept the assignment. Huge mistake.

- PPE. We have it for a reason. Wear it all appropriately, in particular shrouds and gloves.

OVERHEAD

- Who can call for a “Roll Call” to ensure everyone is accounted for? Should it be done at the division or with the Team?

- Command channel was never cleared. Weather was read over Command during the incident.

- It was a difficult unified command. We typically go unified with an IC and maybe OPS, but not unified with two whole teams.

- Trying to meld two Type 1 teams is not advantageous. There are too many voices and it muddies the water. That was happening on this incident. Having Deputy Branches was a side effect of blending two teams together. We had different operational mindsets and they weren’t communicating clearly enough. If we ever have two Type 1 teams again we need to address this more clearly.

- Don’t get down into the weeds. This is very difficult when there is a Branch and a Deputy Branch. They need to stay up and out of weeds.

- Don’t use deputy branches. I will fight tooth and nail not to have a Deputy Branch again. Next time I can isolate branches, make them smaller or broken apart.

- Regardless of how good the plan is, timing is a critical element of the development of the plan. Sometimes we get wrapped up in the plan and fail to reassess the plan. When conditions changed, we needed to reevaluate.

- I should have spoken up sooner. When I drove up, I should have voiced more that this was not a viable plan.

- Put too much time in trying to salvage a line that was already lost.

- I need to ask more questions to get a clearer picture.

- Make sure everyone has a clear plan. The basics. LCES. Where are we going? Who is in charge? Leaders Intent, even if briefing has to be hasty.

- Drop points are not safety zones. TRAs are not safety zones or deployment zones.

- When you have two teams there can be difficulties like one team pushing for one thing and the other team pushing for another. You have to be more vocal. If we make deputy branches, they have to ride in the same vehicle. They cannot divide and conquer tasks because there is confusion about who is in charge.

- We created a hybrid of the ICS system. The two ICs got along great. Below OPS is where it got muddled. Both teams had some failures when it came to how we were organized and communicated below us. Once we got feedback from the field, we cleaned up and it went better. There are definitely ways to make it work better.

- I should have come up on Command and at least notified the medical unit there was an IWI. I should have forced myself to help Branch check those boxes. I’ve been thinking how I could have helped. “At all costs you have to address what you feel isn’t safe.”

- I’m not blaming CAL FIRE or the Forest Service, I’m blaming human nature. We have to let go of what’s on your shoulder [referring to the organization/agency patches].

- Talk to each other. We have qualifications for a reason. At the end of the day, we have to work together and realize there are good people out there in all agencies. Talk with people to determine their experience levels and comfort in different fuel types, conditions, etc. If someone is a qualified division, they are qualified. Base actions on the complexity of what the fire is going to do instead of I don’t know this guy or trust him so I’m going to just take this on myself.

- It took too long for the FLA team to get here. Quite honestly, we were talking to you seven days later. Guys were barely at the hospital when I requested a team. Bring someone in to look at this objectively. I’m a little frustrated that it took a while to get here.

- When we decided to meld the teams, we asked for Agency Administrators and Incident Commanders to get together and have a frank discussion behind closed doors. I believe that should happen more.

- Letter of delegation is not real. You need closed-door discussions and talk about it. This settled things down a bit. It might be a best practice.

- I believe that CAL FIRE and Forest Service are going to work together in the future. Anytime we are going to do that we need to work out HOW beforehand. Every time we have worked out something it’s been during a fire and that’s not the time to do that. We need to look at how both sides operate and drill down how it works and whose going to do what, before the fire bell rings. On the dirt, we fight fire, and it shouldn’t be that different on the teams.

- For me personally, as Operations when I am in the field I try not to be overly involved in tactics so I don’t know all the details of what has already being looked at. If you get too involved you can get things messed up. I should have spoken up sooner. When I drove up I should have voiced more that this was not a viable plan. Looking back, we should have just fired out to protect people. I took for granted that was what was going on.

- Branch was calm when the separation happened. He handled it well. It was textbook on how to help folks that are cut off and running. He asked for resources and kept his voice calm. Once the message was passed to all resources that we would shelter in place in the saddle we realized it was not the best place for a safety zone. People stayed calm, folks understood what they needed to do, and it allowed Branch to deal with separated folks.

- Peer support is important. Having CISM there was awesome. They had a couple of therapy dogs. We now want to have a permanent CISM and dog on our team.

- OPS leadership out there at the time helped people. They had their heads down on the mission and OPS being there may have helped them survive.

- We recognized radiant burns can be misdiagnosed or dismissed as minor or superficial. Blisters and swelling can occur many hours later. The burns need to be looked at by a specialist and we had to convince the doctor to get referral to a specialist. We also had firefighters refusing treatment. One firefighter that went in had red ears the night before and the next day they looked like cauliflower. We need a universal protocol.