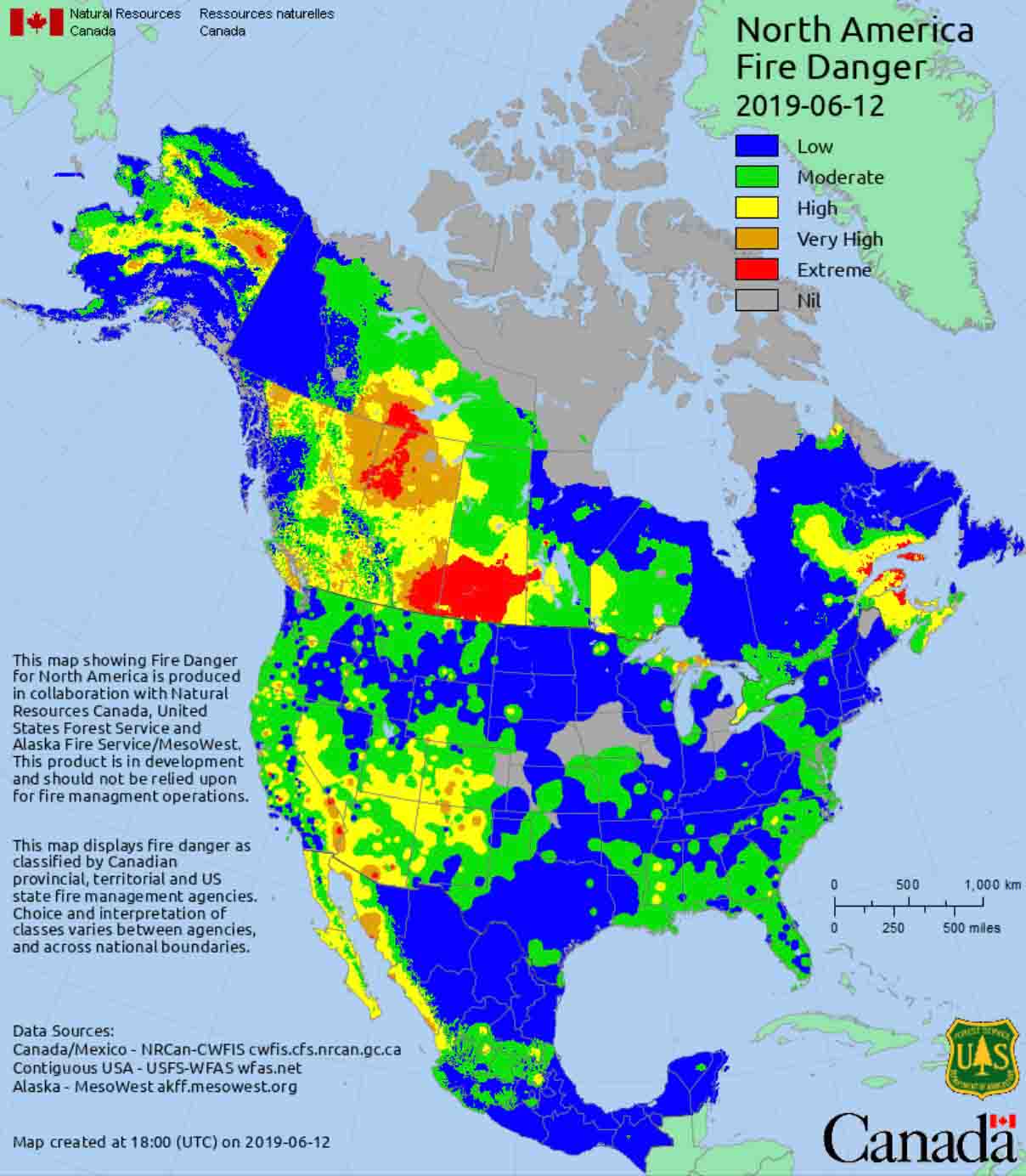

The forests and brush lands of many areas of California are ready to burn. The effects of precipitation received in the winter and spring have been negated by relentless warm, dry, and occasionally very windy weather. The recent Kincade and Maria Fires were examples of wildfire potential during strong winds.

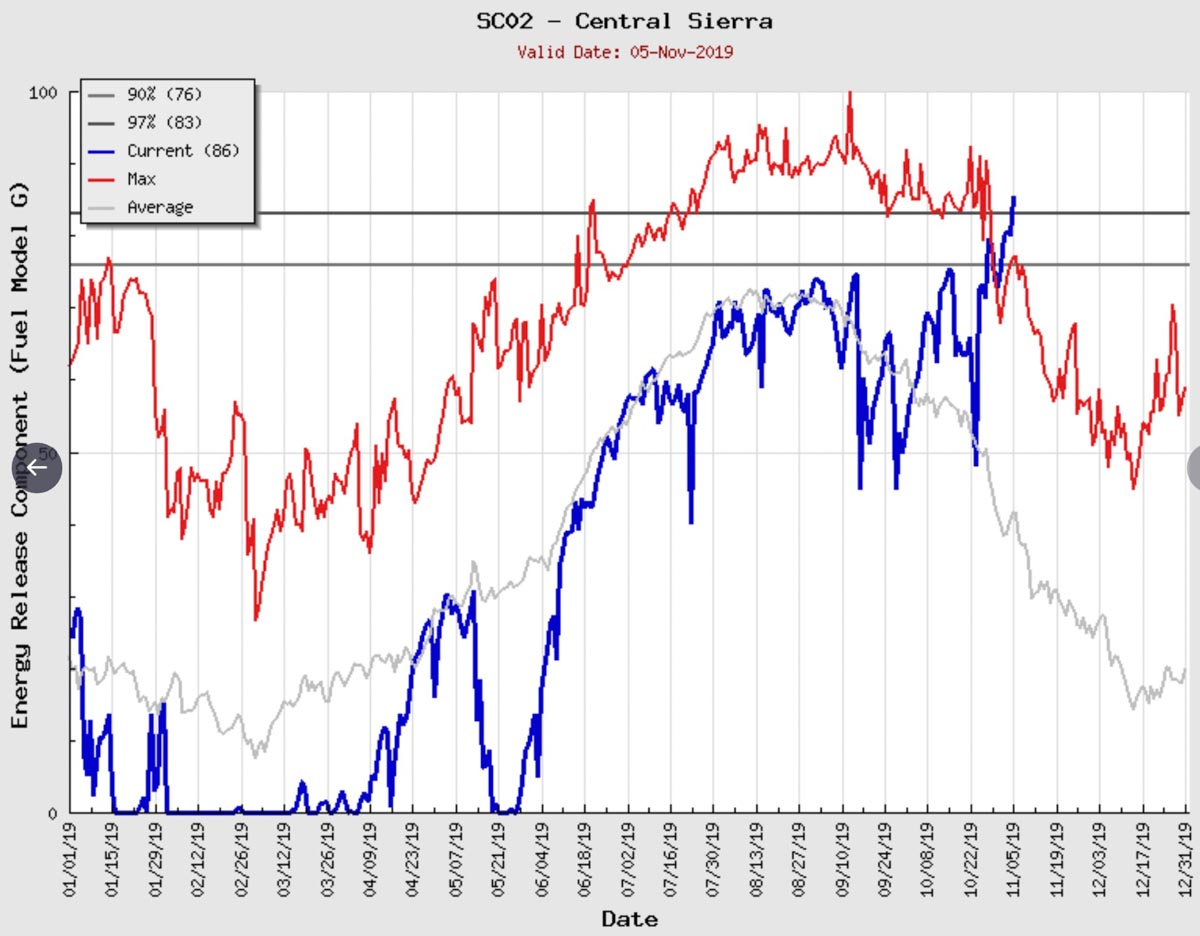

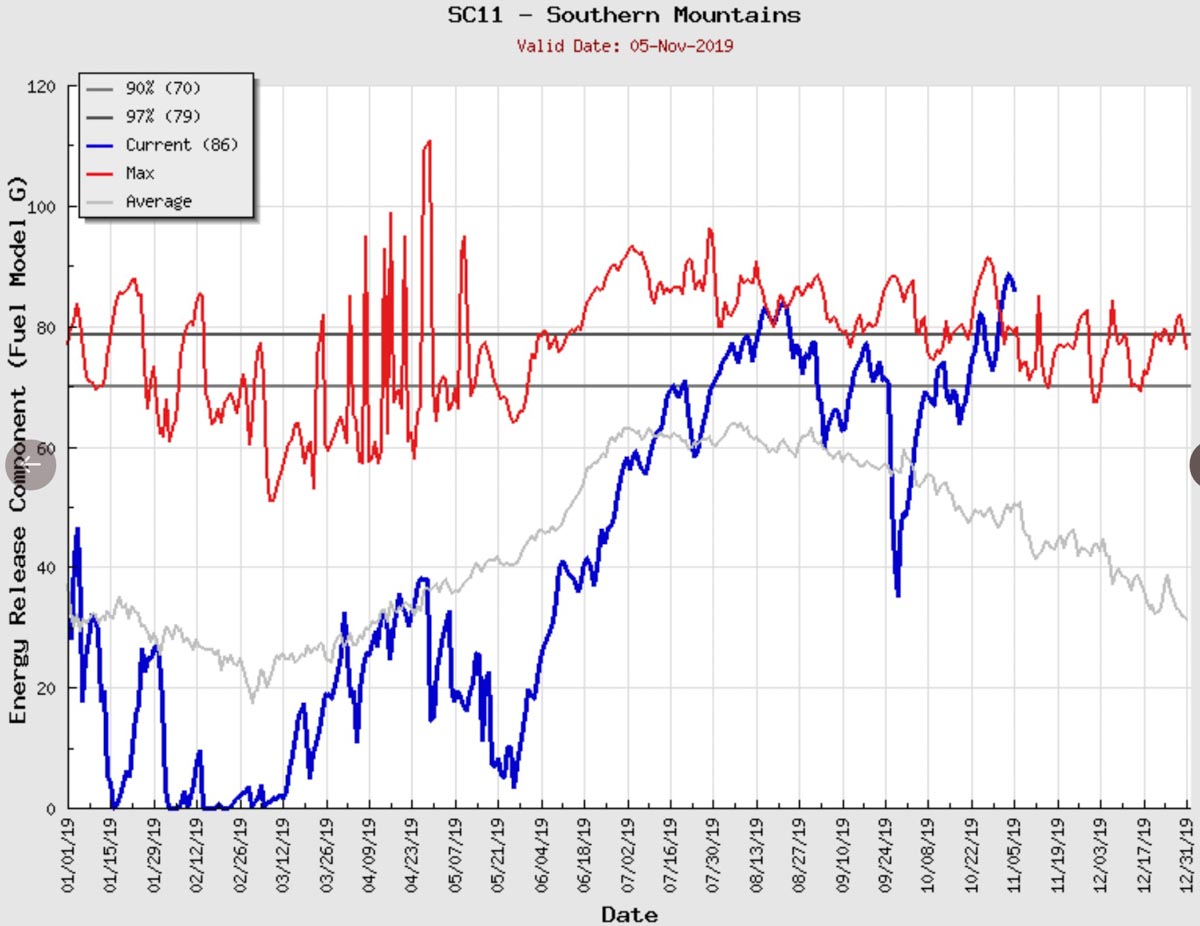

The Energy Release Component (ERC) is a measure of the heat produced within the flaming front of a vegetation fire and is largely influenced by the moisture in the live and dead fuels. In other words, it reflects the flammability of the vegetation. The weather in the last few months in California has resulted in many areas having record or nearly record high ERCs in recent days, including the Southern Mountains, Bay Marine, Central Coast, South Coast, Central Sierra, and Santa Cruz Mountains.

The data in these ERC charts shows the most current levels being above the 97th percentile for any date and close to or above the maximum ever recorded on November 5. (Charts for more areas in California)

One thing that is striking about this information is the ERC in the Central Sierra, an area where the wildfire danger usually drops quickly after September. The conditions we are seeing now are similar to or perhaps more extreme than in 2017 and 2018 before the Camp, Woolsey, Thomas, and North Bay Fires that combined destroyed over 29,000 structures in October, November, and December.

This is not normal. The fire seasons are longer than they were a couple of decades ago.

The fuel is ready now. The only things lacking are very strong winds and an ignition source.

There are no forecasts for very strong winds within the seven days in California, but wind is difficult to forecast and can sneak up on you. There is a possibility for an off-shore flow around November 15.

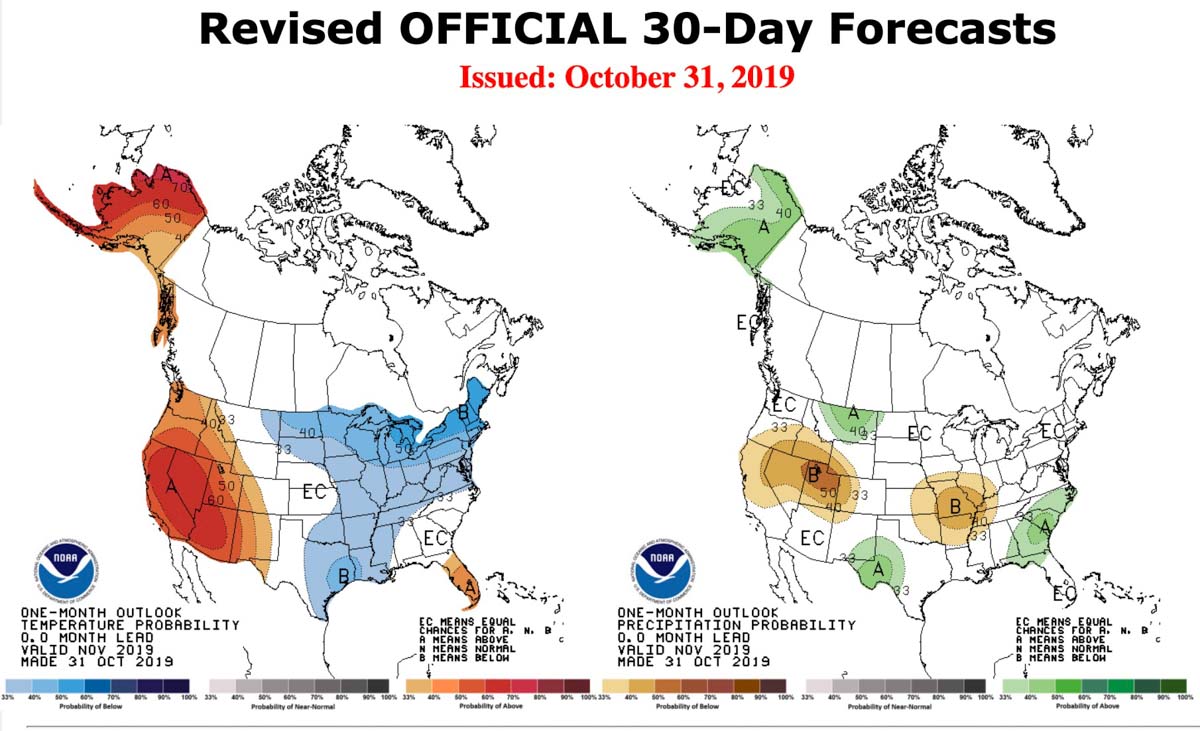

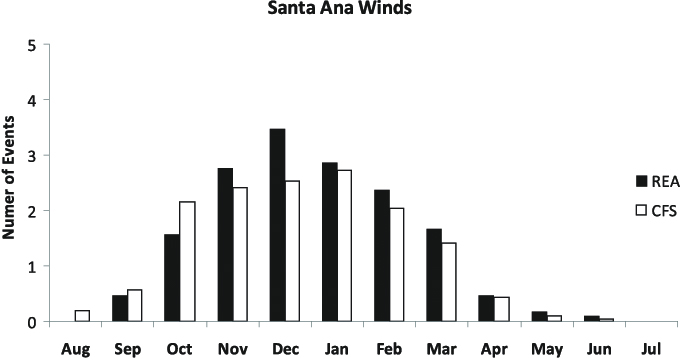

The three months with historically the most Santa Ana wind events are November, December, and January. The forecast for California in November is for higher than average temperatures and precipitation that is at or below average.