We have not heard very much about prescribed fires or fire use fires at Bandelier National Monument since the disastrous Cerro Grande fire of 2000, which began as a prescribed fire then escaped and burned 235 homes in Los Alamos, New Mexico. This interesting article from Fire Engineering describes a fire use fire at Bandelier and has quotes from Dick Bahr and Tom Nichols, who both work for the National Park Service in Boise. Here is an excerpt.

=================================================

By STACI MATLOCK

Last July, people in Los Alamos and Santa Fe looked toward Bandelier National Monument and saw smoke in the air.

Rather than stomp the lightning-caused San Miguel Fire out quickly, Bandelier National Monument let it burn, a counterintuitive move for an agency that only nine years prior had set the blaze destined to became one of the most destructive fires in recent memory. But it was an example of just how much fire management has changed in the last few decades.

Bandelier’s superintendent, Jason Lott, let the San Miguel Fire burn because the weather conditions were right. Fire resources were available if the park’s fire staff needed help, and the fire occurred in an area park staff had already mapped out as needing treatment to reduce flammable forest material. The San Miguel Wildland Fire burned 1,635 acres in the park and Santa Fe National Forest. It left behind patches of burned and unburned vegetation, exactly what forest ecologists like to see. Bandelier’s fire staff only tamped down the fire when it threatened cultural resources or entered risky areas. “Our goal is to allow lightning-ignited fires to burn naturally within fire-adapted ecosystems when we can do so safely, effectively and efficiently,” said Lott at the time.

In centuries past, nature took care of periodically cleaning house in Bandelier and other southwestern forests, sending fire through every 10 to 25 years to kill weak trees and reduce plant debris on the forest floor. Archaeologists and anthropologists have found evidence of ancient native people setting fires to stimulate grass growth.

Then, after the 1871 fire in Peshtigo, Wis., that killed more than 1,000 people, and the Great Fire of 1910 that burned more than 3 million acres in Washington, Montana and Idaho and killed 78 firefighters, wildfire became an enemy to be stopped. From the early to mid-1900s, fire suppression, grazing and logging interrupted the cycle. Western forests became dense and overgrown. “We’ve changed the landscape so that it doesn’t necessarily function as it traditionally did,” said Richard Bahr, lead fire ecologist for the National Park Service in Boise, Idaho.

Bahr said land managers began letting fires burn out naturally again after the 1960s. They were easier to control because the climate was moister and cooler through the 1980s.

Then three factors combined to make forest fires more complicated and more expensive to fight, Bahr said: millions of acres of overgrown forests, more people living in them and a drier, warmer climate.

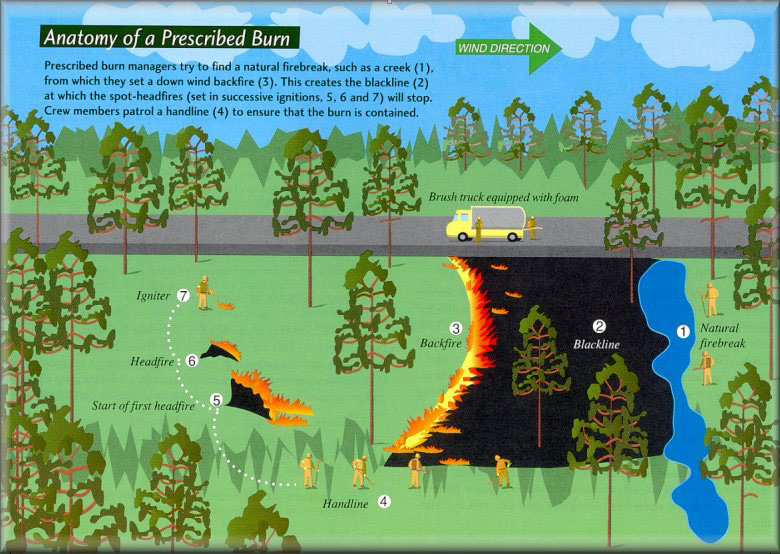

Tom Nichols, chief of fire and aviation for the National Park Service in Boise, said there are three parts to forest fire management — prescribed burns, suppression of fires and letting the fire burn out on its own as in the case of San Miguel.