The research outlined below by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center is further evidence of the importance of smoke management. Land managers, agency administrators, and incident management teams need to constantly consider methods of reducing smoke exposure to firefighters and the downwind population when planning, conducting, or suppressing wildfires and prescribed burns.

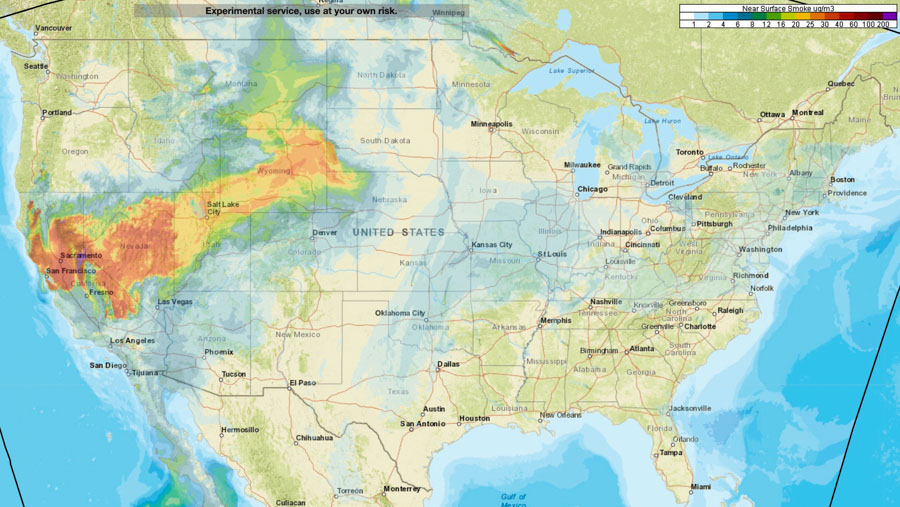

Woodsmoke from massive wildfires burning in California shrouded much of the West last summer, making it harder for people suffering from respiratory illnesses to breathe.

Those respiratory consequences can be dangerous — even life-threatening — but Matthew Campen, PhD, a professor in The University of New Mexico College of Pharmacy, sees another hazard hidden in the smoke.

In research published online this week in the journal Toxicological Sciences, Campen and his colleagues report that inhaled microscopic particles from woodsmoke work their way into the bloodstream and reach the brain, and may put people at risk for neurological problems ranging from premature aging and various forms of dementia to depression and even psychosis.

“These are fires that are coming through small towns and they’re burning up cars and houses,” Campen says. Microplastics and metallic particles of iron, aluminum and magnesium are lofted into the sky, sometimes traveling thousands of miles.

In the research study conducted last year at Laguna Pueblo, 41 miles west of Albuquerque and roughly 600 miles from the source of wildland fires, Campen and his team found that mice exposed to smoke-laden air for nearly three weeks under closely monitored conditions showed age-related changes in their brain tissue.

The findings highlight the hidden dangers of woodsmoke that might not be dense enough to trigger respiratory symptoms, Campen says.

As smoke rises higher in the atmosphere heavier particles fall out, he says. “It’s only these really small ultra-fine particles that travel a thousand miles to where we are. They’re more dangerous because the small particles get deeper into your lung and your lung has a harder time removing them as a result.”

When the particles burrow into lung tissue, it triggers the release of inflammatory immune molecules into the bloodstream, which carries them into the brain, where they start to degrade the blood-brain barrier, Campen says. That causes the brain’s own immune protection to kick in.

“It looks like there’s a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier that’s mild, but it still triggers a response from the protective cells in the brain — astrocytes and microglia — to sheathe it off and protect the rest of the brain from the factors in the blood,” he says.

“Normally the microglia are supposed to be doing other things, like helping with learning and memory,” Campen adds. The researchers found neurons showed metabolic changes suggesting that wildfire smoke exposure may add to the burden of aging-related impairments.

The research team included colleagues from the College of Pharmacy and the UNM Departments of Neurosciences, Geography & Environmental Studies, and Earth and Planetary Sciences, as well as researchers at Arizona State University, Michigan State University and Virginia Commonwealth University.

Story provided by University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center. Original written by Michael Haederle.

Journal Reference:

David Scieszka, Russell Hunter, Jessica Begay, Marsha Bitsui, Yan Lin, Joseph Galewsky, Masako Morishita, Zachary Klaver, James Wagner, Jack R Harkema, Guy Herbert, Selita Lucas, Charlotte McVeigh, Alicia Bolt, Barry Bleske, Christopher G Canal, Ekaterina Mostovenko, Andrew K Ottens, Haiwei Gu, Matthew J Campen, Shahani Noor. Neuroinflammatory and neurometabolomic consequences from inhaled wildfire smoke-derived particulate matter in the Western United States. Toxicological Sciences, 2021; DOI: 10.1093/toxsci/kfab147

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Gerald.