News and opinion about wildland fire

The fire is 6 miles south of Big Bear Lake in southern California

The El Dorado Fire slowly burned down slope towards the Angelus Oaks community Monday night allowing fire resources the opportunity to secure indirect and direct firelines in preparation for active fire Tuesday. Firefighters are prepared to conduct firing operations around Angeles Oaks if needed using hand crews and fire engine crews.

The portion of the fire north of Oak Glen has not spread much in recent days but it was very active Monday and Tuesday south and east of Angelus Oaks where it ran over the ridge and is working its way down to Highway 38 east of the community.

The fire is northeast of Yucaipa, California just west of the Apple Fire that burned 33,000 acres 5 weeks ago, and it is 6 miles south of Big Bear Lake.

Tuesday there was an 8 to 10 mph wind gusting to 20 mph above the 6,000 foot elevation. The weather remains hot and dry. Officials said the fire could align with topography and burn actively upslope towards the San Bernardino Peak (northeast) towards the Lake Fire scar. The threat has increased for the mountain communities north of Highway 38.

The incident management team is having difficulty obtaining the firefighting resources they need.

This blaze which has blackened 17,532 acres and destroyed 4 homes was started by a pyrotechnic device used at a gender reveal party September 5, 2020.

According to the National Situation Report, resources assigned to the fire include 19 hand crews, 205 fire engines, and 11 helicopters for a total of 1,319 personnel.

I asked a fire scientist

September 15, 2020 | 7:45 a.m. PDT

Yesterday President Trump flew in to Sacramento McClellan Airport to receive a briefing on the wildfires ravaging the state. Before he met with the Governor and fire officials he stepped before microphones and provided his opinion about what led to the numerous fires in Oregon and California.

“There has to be good, strong, forest management,” he said, “which I’ve been talking about for three years with the state so hopefully they’ll start doing that.”

(The federal government owns nearly 58 percent of California’s 33 million acres of forestlands, while the state owns 3 percent.)

Then the President talked about exploding trees:

“But with regard to the forest, when trees fall down after a short period of time, about 18 months, they become very dry, they become really like a match stick and they get up you know there’s no more water pouring through and they become very, very they just explode. They can explode.”

The myth of exploding trees may have originated with a classic film about wildfires, “Red Skies of Montana” which showed firefighters being harassed by exploding trees, thanks to movie magic. Then the book “Young Men and Fire” mentioned “the occasional explosion of a dead tree”.

In my 33 years of fighting wildland fires I never saw or heard a tree explode, and I don’t know a reputable firefighter that has.

In 2016 after the late Senator John McCain talked about the Chedeski and Wallow fires in Arizona and “trees literally exploding as the fuels that have accumulated around the bases of the trees burns up,” I reached out to the firefighter community asking if anyone had ever seen a tree explode. No one said they had.

When lightning strikes a tree it can explode when the moisture inside is converted to steam in a millisecond. And maple trees can explode in below freezing temperatures when the sap freezes. There are unconfirmed reports that eucalyptus trees in Australia can explode in a fire but I’m not convinced this is true. I understand that heated gasses or sap can shoot out of a crack in a eucalyptus tree and can be ignited during a fire.

Frank Carroll, in a comment on yesterday’s article about the President’s remarks, said he possessed a video shot with a wildlife camera of a tree exploding in a fire. He also said, “Rothermel theorized that the moisture in the tree is superheated and caused the rapid expansion of gasses that go boom.”

(UPDATE: Mr. Carroll sent me the video, with permission to post it on YouTube. You can judge for yourself if it shows an explosion.)

Since his name had been invoked, I reached out to Richard Rothermel, who is a retired fire scientist. In 1972 he and others developed the Forest Service’s first quantitative, systematic tool for predicting the spread and intensity of forest fires, which introduced a new era in fire management. And surprisingly, it is still the main tool being used today. Many researchers have produced alternative models, but none have made it into the hands of firefighters on a widespread basis.

When Mr. Rothermel began researching the behavior of wildland fires, he had just been downsized from a shuttered Department of Defense program that had been working to develop a nuclear-powered airplane.

I told Mr. Rothermel what was said about him, and asked for his response. He replied within a few hours:

“I have been out of the fire business for a long time and I don’t recall discussing exploding trees. Thats not to say I didn’t, but theorizing the problem now, here is what I think. There may be different concepts of what it means for a tree to explode. One could be that the foliage suddenly bursts into flames due to a massive amount of heat engulfing the tree. That I believe could happen.

“The other which your question prompts me to believe is what is meant by an exploding tree is for the trunk to become super heated sufficiently to cause the moisture in the tree to suddenly become steam with resulting expansion which would shatter the tree. In my years at the fire laboratory I never heard anyone report seeing this or finding evidence of it.

“The problem is the timing, a tree at the fire front could be engulfed in both convective and radiant heat which would transfer heat to the tree’s surface very fast, but the heat would then have to be transported by conduction to the moisture in the cambium layer. Conduction is a very slow method of heat transfer in woody material. In the situation under discussion the fire would be spreading extremely fast and the fire front would have moved on before the heat could have time to boil the water in the cambium layer and cause a steam explosion at the fire front. What could happen after the front has passed and the fire continues to burn if fuels are available is anybody guess.”

UPDATE, September 18, 2020 | 1:32 p.m. PDT:

I first wrote about the myth of trees exploding in 2016 when a senator talked about “trees literally exploding”. I noted then that at least one book and a movie also propagated the myth, and I wanted to dispel it.

When Mr. Trump said trees can explode, I decided to write a followup to the 2016 article, hoping to clear up any confusion, since trees do not explode.

Some of the readers of Wildfire Today were offended by what they saw as criticism, and bent over backwards to make what he said seem reasonable. A person might wonder if they would have put up as strong a defense if the same words had been spoken by a different President.

Bill Gabbert

Wildfire Today

Wildfire News & Opinion, since 2008

Lives lost

The tally of the number of lives lost in the California and Oregon blazes will undoubtedly climb as teams search through the footprints of residences. It took weeks in 2018 to document every fatality at the Camp Fire at Paradise, California. Here are the numbers collected so far by the San Francisco Chronicle:

Structures destroyed

It is difficult to get good consistent numbers about structures that have burned. CAL FIRE usually includes damaged buildings as well as those that have been destroyed. The Incident Status Summary, ICS-209, that incident management teams on a fire submit every day asks for the number that were destroyed. And it is likely that many teams on fires have not had the time to count all of the affected structures.

Here are the numbers of destroyed structures from the September 14, 2020 National Incident Management Situation Report compiled at the National Interagency Coordination Center, broken down by Geographic Areas. It uses data from the ICS-209:

Acres burned

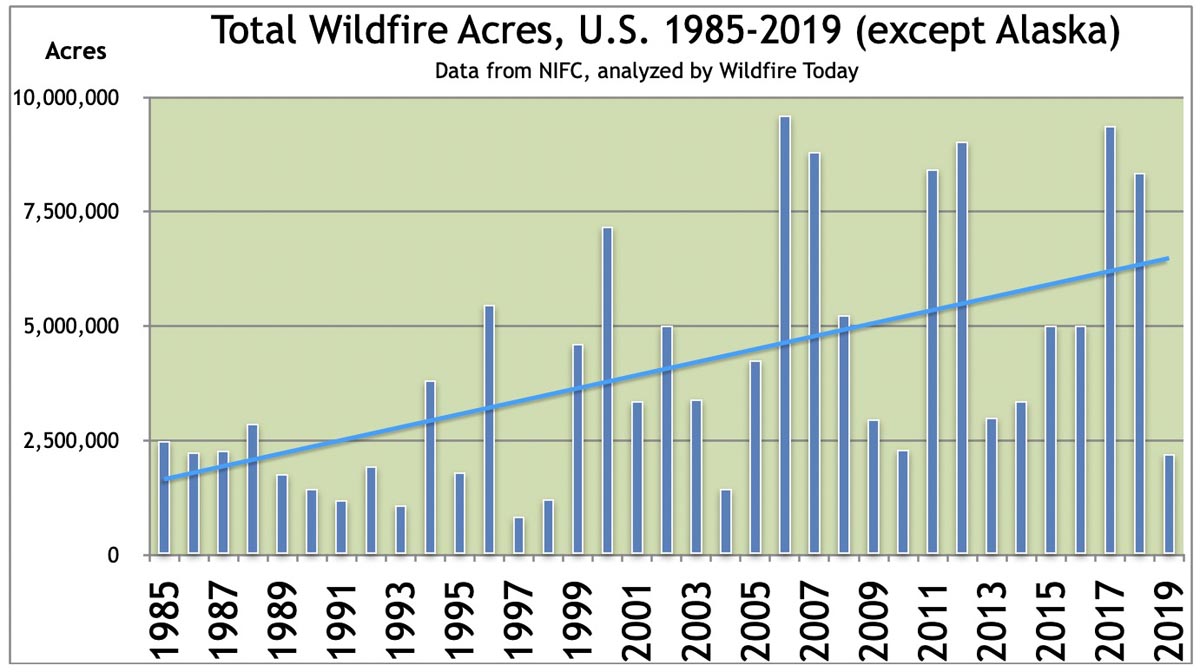

The fire season is not over in all areas, but the number of acres burned to date has exceeded the 10-year average number burned in a year. But the figure varies greatly from year to year. 2019 had the least number since 2004, when considering only the states outside of Alaska.

5,887,136 — The total number of acres burned to date in the U.S., not counting Alaska

5,608,376 — 10-year annual average number of acres burned in the U.S., not counting Alaska

There have been many large fires in the last one to two months in Arizona, California, Oregon, Colorado, and Washington, but it has been quieter than usual in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

After landing at Sacramento McClellan Airport September 14, 2020 to meet with Governor Gavin Newsom about the California fires, the president stopped to talk to reporters. With a P-3 air tanker in the background, he recognized the assistance the federal government is providing. He also talked about how dry trees explode and a subject he has brought up many times, forest management. (Truth check: trees do not explode, whether from being dry, or during a fire. Except — it can happen when struck by lightning.)

McClellan is a very busy air tanker base these days reloading large and very large air tankers. Sometimes airports are completely shut down when the President is on the ground anywhere nearby, so I asked @SocalAirOps if it was closed during the visit and the answer was no, T-944 (the 747) took off while the President was on the ground. And @JudyMichelson1 chimed in to say T-107 (an MD-87) also took off.

The transcript below of the Presidents’s remarks begins a few seconds after he stepped in front of the reporters. He also spoke to reporters at least one other time while at Sacramento.

President: …Washington state and Oregon and I think they’ll go very well. I think they are doing an incredible job. This is one of the biggest burns we’ve ever seen and we have to do a lot about forest management. Obviously forest management in California is very important and now it extends to Washington and extends also to Oregon. There has to be good, strong, forest management which I’ve been talking about for three years with the state so hopefully they’ll start doing that. In the meantime we’re helping them up, out in a very big way. We have the best people in the world doing this. We have all of our people from FEMA, we have law enforcement here. We have the Army Corps of Engineers. We have basically some other military and military operatives that do this. And I’m going to meet with the Governor right now Gavin Newsom. We’ve worked very well together. I’ve approved the emergency declaration as you know. And I think we’ll have a very good meeting.

[…]

Reporter: What would you like to see specifically done on the issue of forest management, and is it possible that it’s also forest management and climate change, it’s both things at the same time.

President: I think something’s possible. I think a lot of things are possible. But with regard to the forest, when trees fall down after a short period of time, about 18 months, they become very dry, they become really like a match stick and they get up you know there’s no more water pouring through and they become very, very they just explode. They can explode. Also leaves. When you have years of leaves, dried leaves on the ground it just sets it up. It’s really a fuel for a fire. So they have to do something about it.

They also have to do cuts, I mean people don’t like to do cuts but they have to do cuts in between, so if you do have a fire and it gets away you’ll have a 50-yard cut in between, so it won’t be able to catch to the other side, they don’t do that.

If you go to other countries, you go to Austria, you go to Finland, you go to many different countries and they don’t have fires. I was talking to the head of a major country and he said, “We’re a forest nation. We consider ourselves a forest nation.” This was in Europe. I said that’s a beautiful term. He said, “We have trees that are far more explosive.” He meant explosive in terms of fire. But we have trees that are far more explosive than they have in California, and we don’t have any problem, because we manage our forests.” So we have to do that in California too.

(end of transcript)

Before you leave a comment, keep in mind that we do not cover politics at Wildfire Today except how it may directly affect wildland fire or firefighters. Feel free to discuss your thoughts or the President’s words about fire suppression and forest management, but please stay away from political parties, candidates, personal attacks, or recommendations about for whom to vote. If this becomes a political free-for-all, I’ll close the article for comments.

September 14, 2020 | 10:35 a.m. PDT

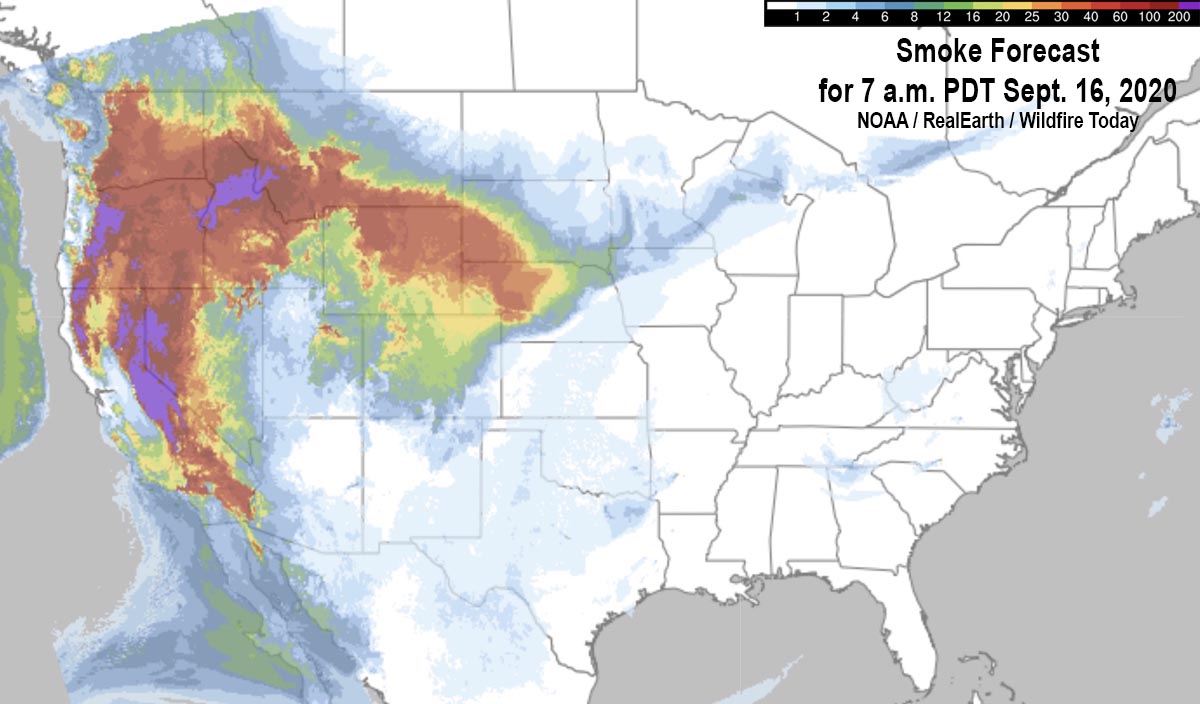

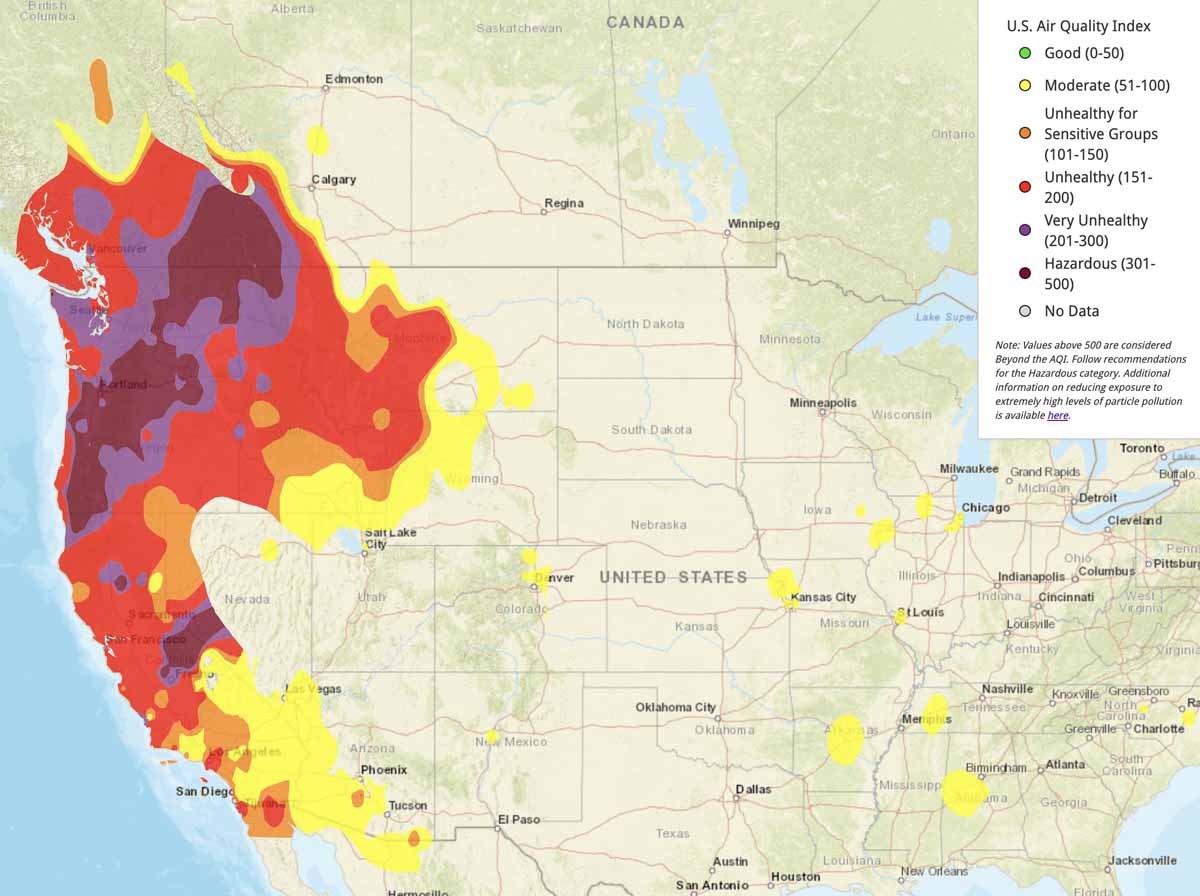

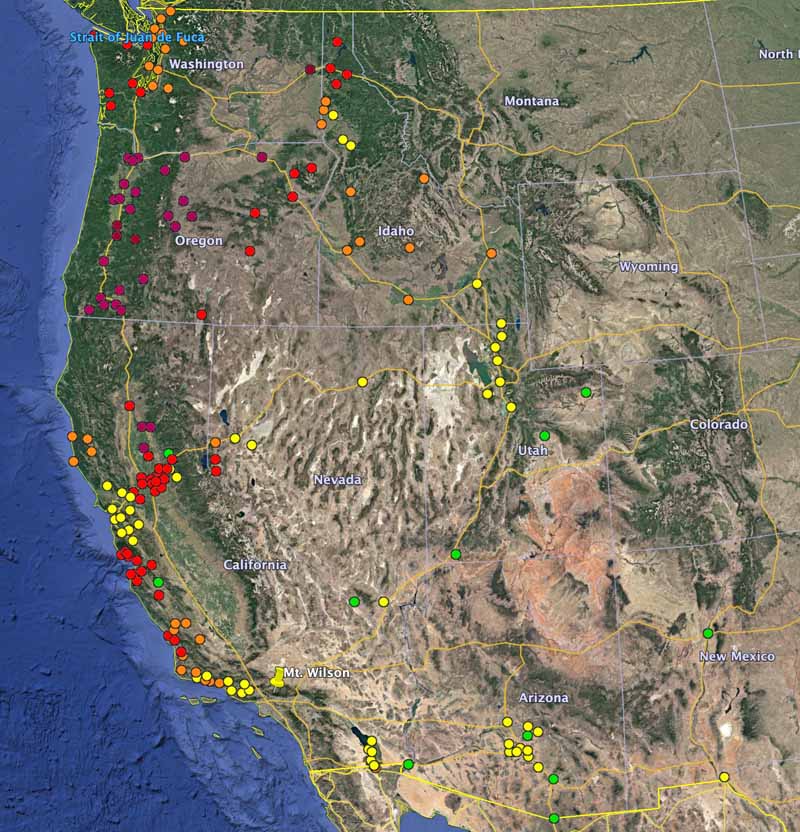

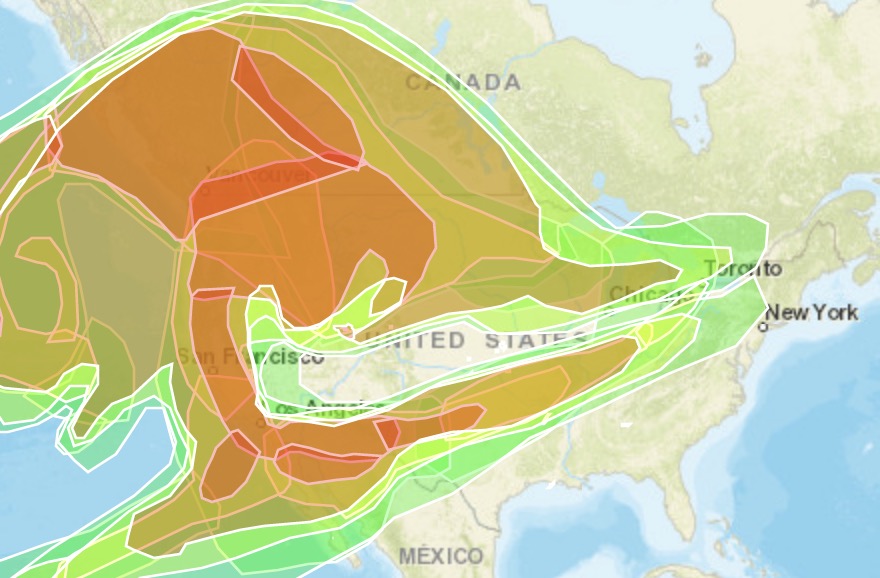

The fires in Oregon, Washington, and California continue to produce large quantities of smoke affecting air quality in those states and portions of Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, Nevada, and Arizona.

The forecast for Tuesday, below, shows improvement in the San Francisco and Los Angeles areas.

(Information on Wildfire Today about how to reduce your exposure to smoke.)

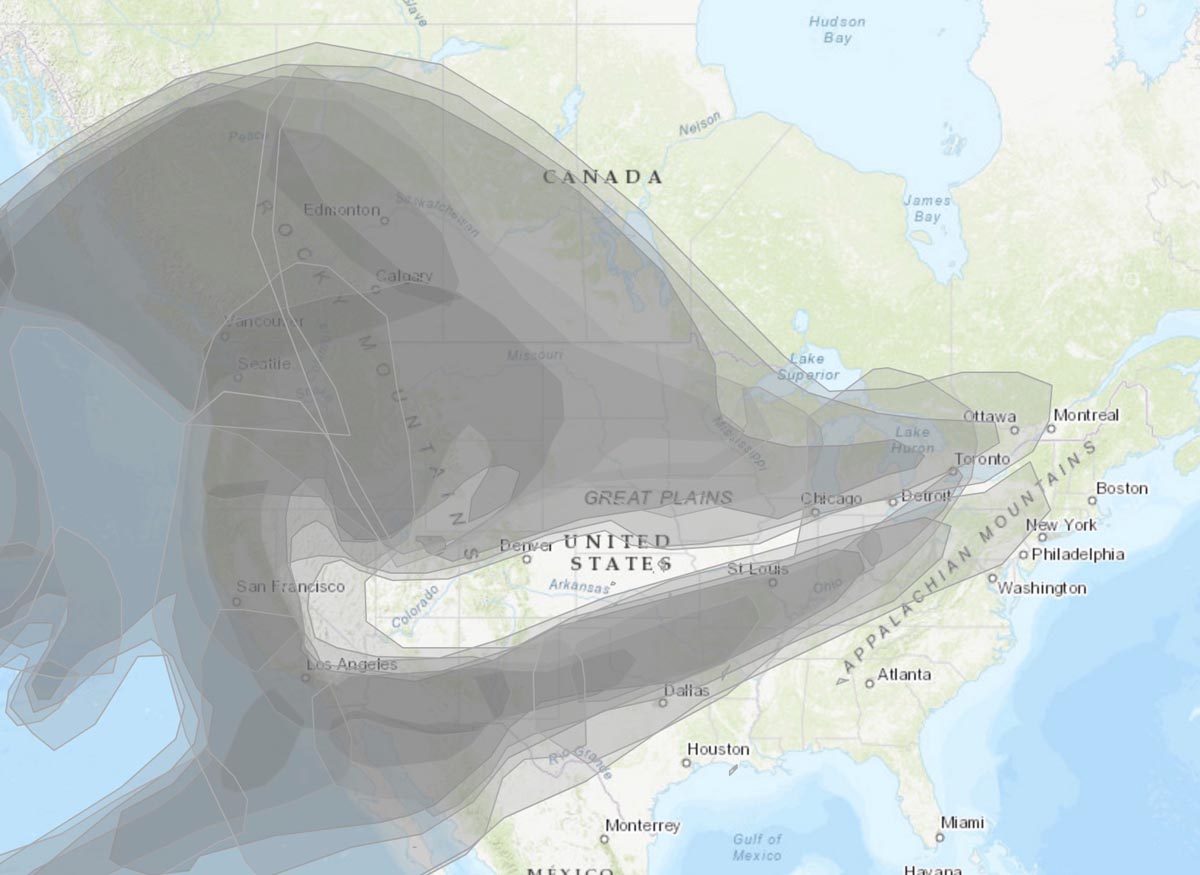

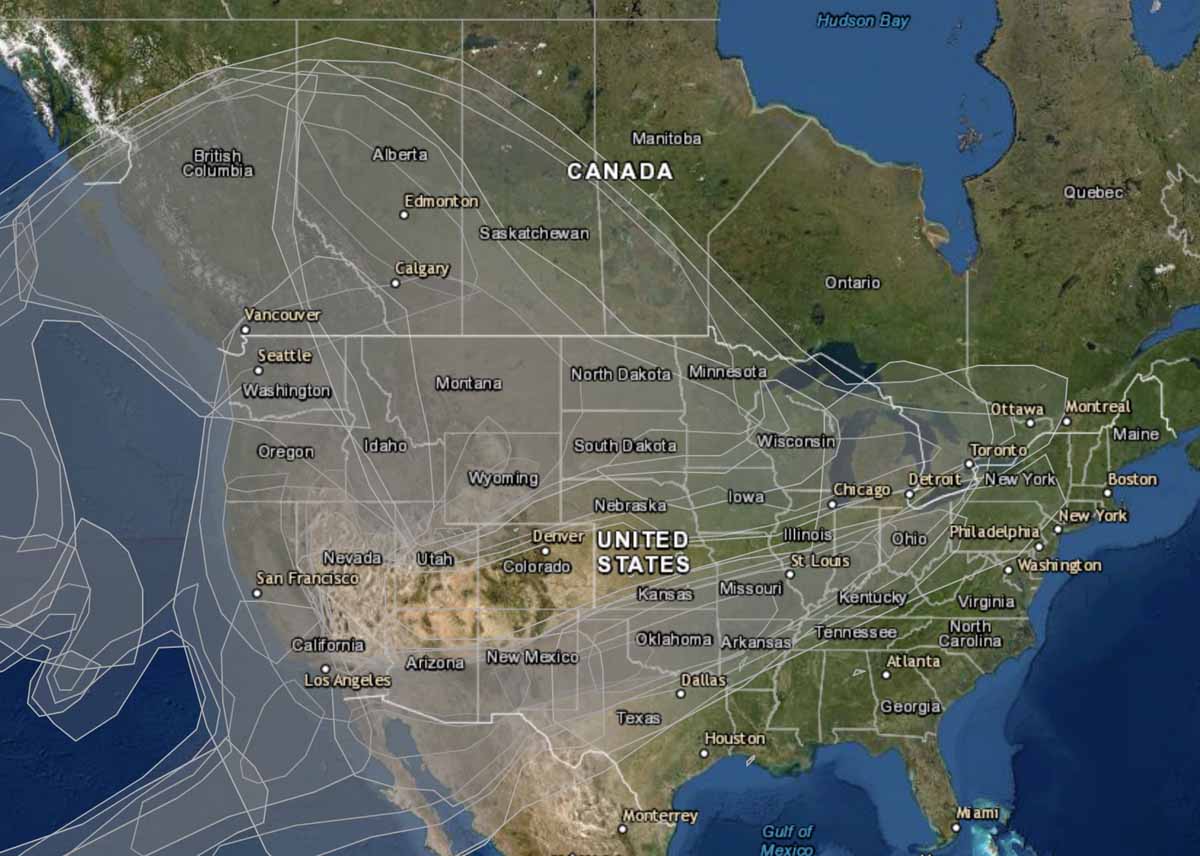

Below is current information about smoke dispersion across the U.S. and Canada. It is tough to find good, easy to read maps that show concentrations of wildfire smoke across the United States. The backgrounds in some cases obliterate the smoke information or the state boundaries.

If you find a good smoke map, let us know in the comments.

The NOAA webpage with the map below sometimes has smoke data, and sometimes it doesn’t. It also has this, seen today September 14, 2020: “Please note that this web page that you are currently on will be permanently retired on September 7, 2020.” There is a link to a different page, but I was unable to quickly find a substitute map.

The next two maps from AirNow have the same smoke data, but there is a choice of two background maps, terrain or aerial.