October 8, 2020 | 1:04 p.m. MDT

An article at National Public Radio recommends what we should be focusing on when discussing the effects of wildfires instead of simply the number of acres burned.

That general topic can cover not only the dollars spent while knocking down the flames, but the actual cost of damage to infrastructure, community water sources, flooding, mud slides, health effects of smoke on populations, repairing the damage done in the burned areas, rebuilding structures, mental health of residents, and the economic effects of evacuations and reduced tourism.

Here is an excerpt from the NPR article:

Often, the human cost of wildfires has little to do with their size. California’s three most destructive wildfires aren’t among the state’s largest. The 1991 Tunnel fire in the Oakland hills was relatively tiny at 1,600 acres, but destroyed 2,900 structures and killed 25 people. Even the Camp Fire, which burned more than 18,000 structures in Paradise, California, isn’t even in the top 20, ranked by acreage.

“I think we should concentrate more on the human losses,” says Ernesto Alvarado, professor of wildland fire at the University of Washington. “Wildfires in populated areas, it doesn’t matter what size those are.”

Public authorities could also report on a broader human impact: the number of people experiencing harmful air due to smoke. While detailed maps are available with smoke concentrations, showing the air quality index, there are few measures of the scale of that public health impact. Poor air quality due to smoke is linked to a rise in emergency room visits due to asthma, stroke and heart attacks.

The article reminded us of one we published April 18, 2014, titled, “The true cost of wildfire.” For Throwback Thursday, here it is again:

A conference in Glenwood Springs, Colorado on Wednesday and Thursday of this week explored a topic that does not make the news very often. It was titled The True Cost of Wildfire.

Usually the costs we hear associated with wildfires are what firefighters run up during the suppression phase. The National Incident Management Situation Report provides those daily for most ongoing large fires.

But other costs may be many times that of just suppression, and can include structures burned, crops and pastures ruined, economic losses from decreased tourism, medical treatment for the effects of smoke, salaries of law enforcement and highway maintenance personnel, counseling for post-traumatic stress disorder, costs incurred by evacuees, infrastructure shutdowns, rehab of denuded slopes, flood and debris flow prevention, and repairing damage to reservoirs filled with silt.

And of course we can’t put a monetary value on the lives that are lost in wildfires. In Colorado alone, fires since 2000 have killed 8 residents and 12 firefighters.

The total cost of a wildfire can be mitigated by fire-adaptive communities, hazard fuel mitigation, fire prevention campaigns, and prompt and aggressive initial attack of new fires with overwhelming force by ground and air resources. Investments in these areas can save large sums of money. And, it can save lives, something we don’t hear about very often when it comes to wildfire prevention and mitigation; or spending money on adequate fire suppression resources.

Below are some excerpts from a report on the conference that appeared in the Grand Junction Sentinel:

[Fire ecologist Robert] Gray said the 2000 Cerro Grande Fire in New Mexico ended up having a total estimated cost of $906 million, of which suppression accounted for only 3 percent.

Creede Mayor Eric Grossman said the [West Fork Complex] in the vicinity of that town last summer didn’t damage one structure other than a pumphouse. But the damage to its tourism-based economy was immense.

“We’re a three-, four-month (seasonal tourism) economy and once that fire started everybody left, and rightfully so, but the problem was they didn’t come back,” he said.

A lot of the consequences can play out over years or even decades, Gray said.

He cited a damaging wildfire in Slave Lake, in Alberta, Canada, where post-traumatic stress disorder in children didn’t surface until a year afterward. Yet thanks to the damage to homes from the fire there were fewer medical professionals still available in the town to treat them.

“You’re dealing with a grieving process” in the case of landowners who have lost homes, said Carol Ekarius, who as executive director of the Coalition for the Upper South Platte has dealt with watershed and other issues in the wake of the 2002 Hayman Fire and other Front Range fires.

The Hayman Fire was well over 100,000 acres in size and Ekarius has estimated its total costs at more than $2,000 an acre. That’s partly due to denuded slopes that were vulnerable to flooding, led to silt getting in reservoirs and required rehabilitation work.

“With big fires always come big floods and big debris flows,” Ekarius said.

Gray said measures such as mitigating fire danger through more forest thinning can reduce the risks. The 2013 Rim Fire in California caused $1.8 billion in environmental and property damage, or $7,800 an acre, he said.

“We can do an awful lot of treatment at $7,800 an acre and actually save money,” he said.

Bill Hahnenberg, who has served as incident commander on several fires, said many destructive fires are human-caused because humans live in the wildland-urban interface.

“That’s why I think we should maybe pay more attention to fire prevention,” he said.

Just how large the potential consequences of fire can be was demonstrated in Glenwood Springs’ Coal Seam Fire. In that case the incident commander was close to evacuating the entire town, Hahnenberg said.

“How would that play (out)?” he said. “I’m not just picking on Glenwood, it’s a question for many communities. How would you do that?”

He suggested it’s a scenario communities would do well to prepare for in advance.

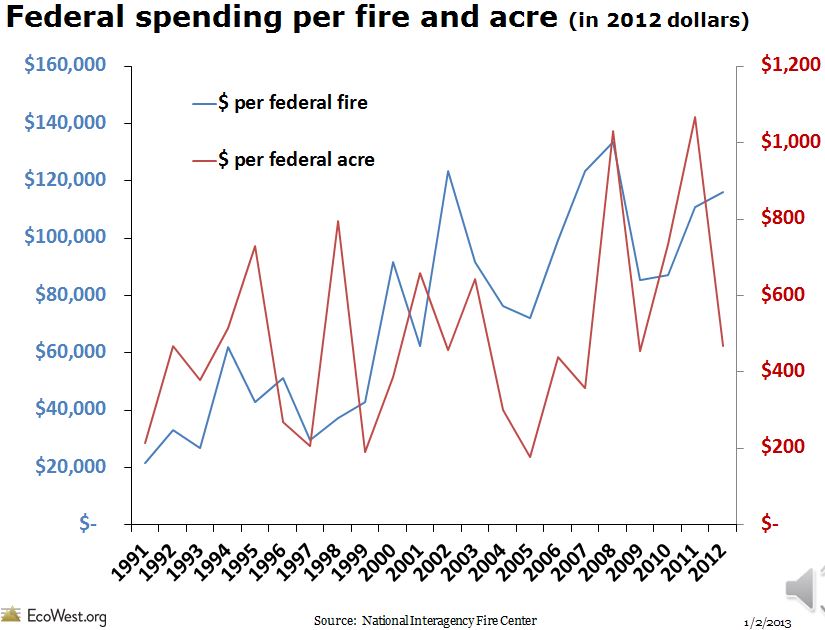

The chart below from EcoWest.org shows that federal spending per wildfire has exceeded $100,000 on an annual basis several times since 2002. Since 2008 the cost per acre has varied between $500 and $1,000. These numbers do not include most of the other associated costs we listed above. (click on the chart to see a larger version)

“We can do an awful lot of treatment at $7,800 an acre and actually save money . . . ”

Thanks for writing this up, Bill. But review the quotations and text carefully and ask, “How much if this has been repeated and repeated, and how much is essentially finger-wagging by authorities?”

Some people simply can’t afford to protect their structures, thinning/defensible space is rarely if ever properly done from a fire behavior/management standpoint and actual consequences, and a lot of suppression expense is futile and costly in terms of lives and equipment losses.

I ain’t no expurt, but it seems to me that if truly effective ($200 bucks might help, but it’s not enough) on-site, independent, automatic/remote-controlled, inside and outside fire suppression systems we financed by government, especially for those who are just getting by, most structure fires could be hit while small enough (firebrands, drifts of same, and of limited progression, professional suppression crews and equipment could largely be confined to the wildlands, especially if strategies were developed to squeeze the fire (especially wind-driven) at its flanks at a point where effective containment and control could be achieved and spot fires dealt with while their size was smaller than the capability rather than larger.

Don’t forget that there is great loss of fauna, we should also respect the animals’ deaths.

Back in the day, we were calling Cerro Grande the first billion dollar fire. Here are the figures I pulled out of a 2001 PowerPoint:

Suppression $ 25 million

Forest Service Rehab $ 35 million (5 yrs.)

Corps of Engineers Projects $ 18 million

NRCS projects $ 1 million

LANL Special Appropriation $260 million

Cerro Grande Claims Act $690 million