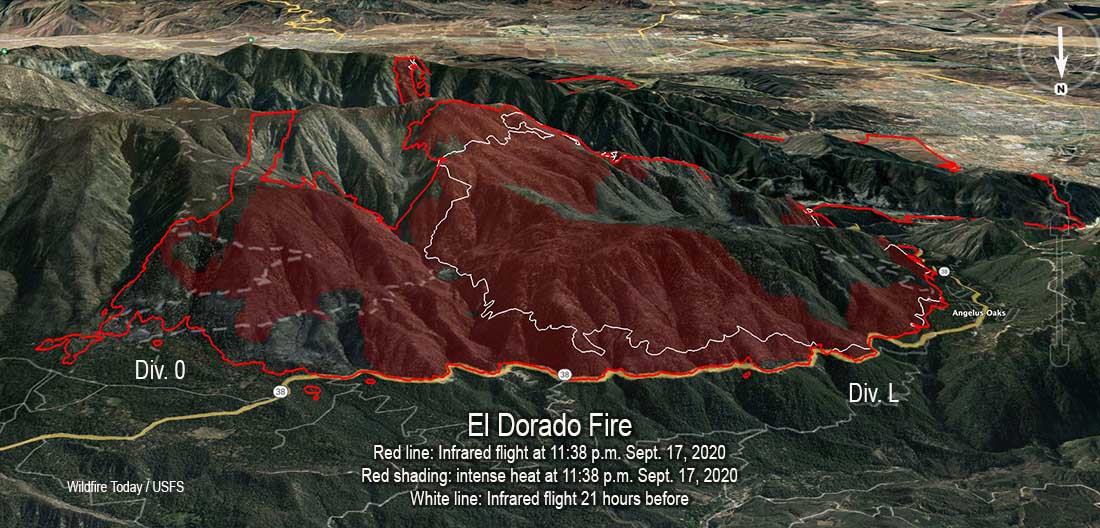

About 15 months after Charles ‘Charlie’ Morton was fatally burned on the El Dorado Fire on the San Bernardino National Forest in Southern California, the US Forest Service released a series of reports about the incident.

According to one of the documents, titled Narrative, Charlie, a squad leader on the Big Bear Interagency Hotshot Crew was scouting the fire alone around 7 p.m. September 17, 2020 when it overran his location. Crews had just stopped igniting a burnout. As the fire intensity increased, one of the crew captains asked him on the radio if he was going to be able to get out of the area. Charlie’s response was, “We’ll see.” Following that, the Captain called him several times with no response. He then heard Charlie call in desperation, “I’m in a corner.” It was the last time he transmitted on the radio.

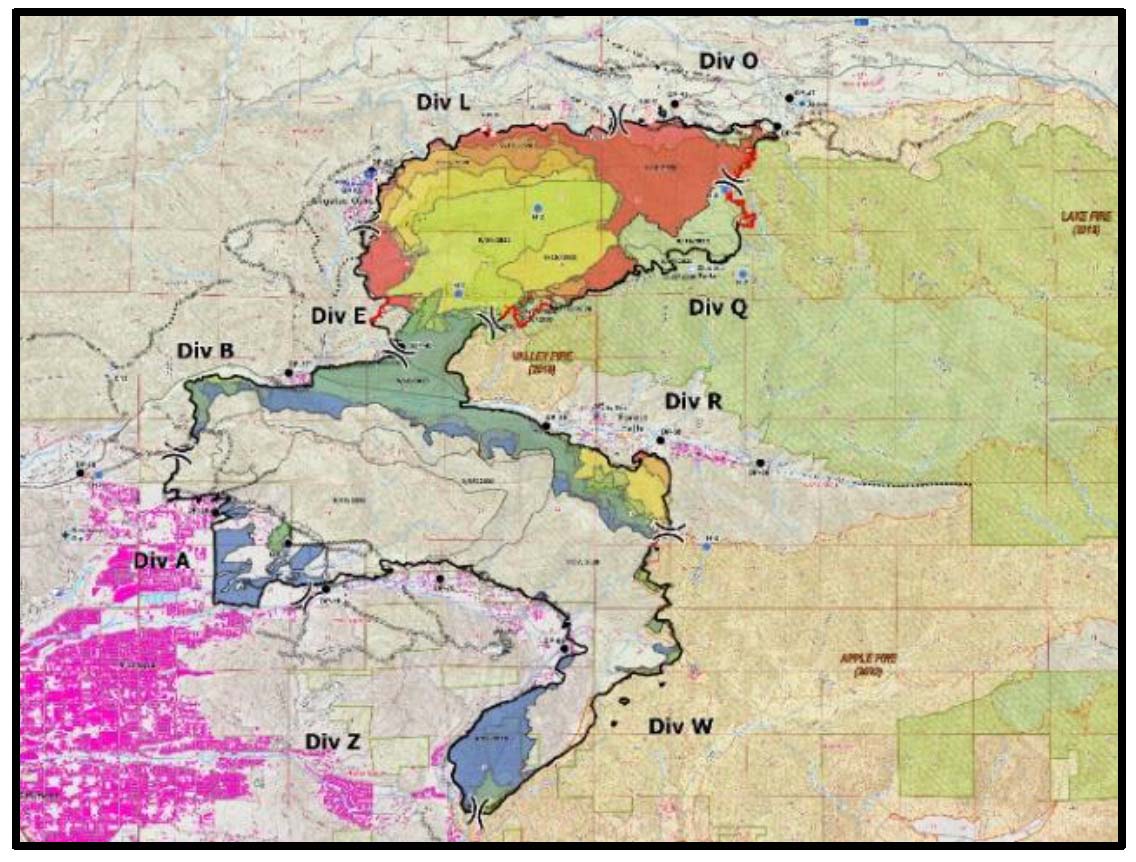

Due to extreme fire behavior, including counter-rotating vortex pairs that formed at his exact location as a result of the burnout operation underway, it was hours before anyone could access Charlie’s location. During that time he was assumed to be missing and the Operations Section Chief assigned the Contingency Branch Director as the Incident-Within-an-Incident Commander to lead the search.

For nearly two hours a sheriff’s helicopter utilized their loudspeaker to call out “If you are a lost hotshot firefighter, give us a signal. If you are a lost hotshot firefighter, give us a signal.” At that time firefighters were very busy attempting to suppress numerous spot fires. Some of them were not aware of the missing firefighter when they heard the announcement from the helicopter.

From the Learning Review Narrative, about the beginning of the search:

BR 5 [Branch Director 5] tried to gain access to the bulldozer line from the Camp Round Meadow area and was accompanied by Division L Medic. Although the medic had limited wildland fire experience, it was apparent that the situation was dangerous. He noted falling snags, extreme temperatures, and that fire flanking below them could cut off their egress back to Camp Round Meadow. He thought he was going to die in there and sent a pin of his location to the Division O Medic so that someone could locate Division L Medic if something bad happened.

Meanwhile, SBC Type 2 Initial Attack Crew tied in with Branch and was allowed to fly a small [CAL FIRE] drone equipped with an infrared camera down the bulldozer line to assist with the search. Drone footage showed significant heat along the line which rendered the infrared camera useless. They switched camera modes and flew a few more missions searching various areas.

The conditions were so dangerous that the Safety Officer decided to call off the ground search.

The time of day or night was not mentioned very often in the report, but some time later:

Big Bear captain 1B (who was filling the role of DIVS L trainee) arrived and announced that he was going to search at the bottom of the bulldozer line. BC#1 [Battalion Chief] didn’t want him to go into the area alone, so he decided to join. Big Bear Captain 1B searched the right side of the bulldozer line and BC#1 searched the left. Even with their big flashlights, it was difficult to see through the darkness, smoke, and flames. A quick reflection of light from an accordioned and undeployed fire shelter caught BC#1’s eye on the edge of the bulldozer line near a bend. They stopped 25 feet away and were able to determine that Charlie had not survived.

The area was still very hot and smoky, and the captain and BC#1 returned to the road below. A medic suggested that she could go to the scene to pronounce Charlie’s time of death, but the decision was made that it was too dangerous. The Safety Officer inserted guards at the bottom of the bulldozer line to keep people from going to view the scene and to prevent another fatality.

At the bottom of the bulldozer line, BR V blew past the guards and went up to the site to be with Charlie and stayed there with him. Some people said to just let him go, but after a period time people began to assume that BR V was fatally lost as well. A second search was organized for BR V. Searchers were unable to access the site due to the heat and falling trees. For approximately a two-hour period, nobody was able to reach BR V because his radio and his cell phone were left in the pickup. Division O Medic returned to stage at DP 45, now waiting to render aid if needed. About 0145, BR V returned down the hill and notifications were passed that he was safe. BR V came down the hill as soon as he realized he’d left his communication devices in his truck.

Charlie is survived by his fiancée, a daughter, parents, and two brothers.

The fire began at 10:23 a.m. September 5, 2020 in the El Dorado Ranch Park in Yucaipa. It was caused by the use of a smoke generating pyrotechnic device. The intent was to produce pink or blue smoke to inform bystanders about the gender of a fetus. A couple was charged with involuntary manslaughter and 29 other crimes.

Other reports

The information above came from the Narrative, a 29-page document that unlike recent facilitated learning analysis (FLA) documents, only covers the very, very detailed chronological facts of what happened on September 17 on the north side of the El Dorado Fire. It does not address, like the FLA for the Cameron Peak Fire for example, 250 Lessons Learned broken down into 14 types of resources (e.g. Finance Unit, Contractors) and 7 categories (e.g. COVID mitigations and testing/contact tracing).

But two other documents were also released about the fatality:

- Report on the personal protective equipment

- Organizational Learning Report

The latter, the Organization Learning Report, breaks with recent established practices, as the Narrative did.

It does not drill down into minutia of what occurred on the El Dorado Fire. It looks at it from 30,000 feet and extrapolates the significance on a much broader scale about the current state of wildland fire management.

It was led by Bill Avey who was appointed to the position of acting director for Fire and Aviation Management in Washington for five months in 2021. He retired December 31, 2021 as the Forest Supervisor of the Helena-Lewis and Clark National Forest in Montana.

Below are excerpts from the seven-page Organization Learning Report. It appears that much of the information came from interviews — not all of the topics are covered in the Narrative. For example, it suggests that perhaps firefighters (or forestry technicians) should be called “fire responders” so they don’t “view fire as an enemy.” Other than that many of their conclusions are very reasonable, even though most of them have been previously identified in various forms. But having so many of them listed in one fatality report is unique, and could be useful. Unless it just disappears into files like so many others.

In his September 24, 2020 testimony before Congress, John Phipps, the Forest Service’s Deputy Chief of State and Private Forestry, stated “the system is not designed for this,” to illustrate the misalignment between the design of the wildland fire system and the reality that wildland fire responders routinely experience.

…

The El Dorado Fire burned as an area ignition resulting from high accumulations of long-burning fuel materials present in the unhealthy forest conditions at the time of the fire. This type of fire behavior was once rarely seen among our wildland fire responders but is becoming increasingly more common because of the current condition of our forests and the influences of climate change. Our current paradigm of treating fire as an enemy that must be defeated contributed to the condition of the forest at the time of the fire. Until we figure out a way to form a new, sustainable relationship with fire, we can expect forest conditions to continue to deteriorate. This deterioration will continue to make situations like this fatality event more probable into the future. We need to see fire’s role on the landscape differently.

…

Viewing fire as the enemy also may have had an influence on local resources “trying to protect their home turf” against that enemy. We are trapped in the paradigm laid out by the philosopher William James’s “Fire is the moral equivalent of War” essays of the early 20th century. Calling our fire employees “firefighters” only contributes to the metaphor of declaring war on an enemy. Perhaps a shift in language (to say…fire responders) may prove beneficial.

…

We continue to ask our wildland fire responders to save communities that are becoming increasingly unsavable. At what point do we declare communities without any semblance of defensible space not worth the risk of trying to save under extreme fire behavior conditions?

…

Two common refrains were heard: “Why am I risking my life and losing time with my family for such futility?” and “The things we did ten years ago are no longer working.” Wildland fire responders feel increasingly isolated and misunderstood, with the expectations from the agency and society to “save the unsavable” while “managing risk.” This coupled with the pay, work-life balance, and hiring issues is eroding the trust and the implicit social contract among wildland fire responders, the Forest Service, and American society. This is another other factor that is quickly resulting in a lack of qualified (or any) applicants and the growing vacancies in fire response crews. On the El Dorado fire, due to a lack of resources, there were four Interagency Hotshot Crews on an incident that would normally have ten.

…

The wildland fire culture has developed in such a way as to defer to the expertise of IHC crews above most other resources on a fire. If the hotshots like the plan, then it must be a good plan…or so the thinking goes. While this heuristic has treated the fire service well in the past; it becomes more problematic if deference is given mistakenly to a resource without the level of expertise that is assumed. Over the course of the last several years, the experience levels of hotshot crews have become diluted. Long-tenured Interagency Hotshot Crew Superintendents seem to be becoming a thing of the past. The Big Bear Interagency Hotshot Crew (IHC), due to a lack of available experienced personnel and coupled by issues with the temporary hiring process, were staffed by a significant number of Administratively Determined (AD) hires, formerly unheard of for an Interagency Hotshot Crew.

…

As federal Interagency Hotshot Crews continue to train and then lose the next generation of leaders, the question must be asked: “At what point will our hotshot crews’ experience levels thin out too much to fill the role we have traditionally asked of them?” And once that occurs, how should we fill that void?

…

The same concerns exist for Incident Management Teams (IMT). With the reduction of 39 percent of the Forest Service’s non-fire workforce since 2000, the “militia” available to assist in IMT duties is rapidly being reduced to a mythical entity, often spoken of but rarely seen. The 2020 fire year was simply the latest in a long string of years where we did not have enough IMTs, let alone general resources, to address suppressing fire in our current paradigm. On the El Dorado Fire, Region 5 took a creative approach to ensure Type 1 oversight by grafting a Type 1 incident commander onto a Type 2 team, when no Type 1 teams were available. While this met the need and policy requirements, one cannot help but wonder what the difference really is between a Type 1 and Type 2 team. Why not just create one national team typing system, and why not ensure that it is staffed to a holistic fire management response (see Theme 2) and not just a direct perimeter control response.

…

Scouting fire lines has proven to be a dangerous task. What barriers prevent federal crews from being able to deploy drones to do the preliminary scouting, rather than having a person do it? How do we overcome those barriers? Note: CAL FIRE crews owned and operated drones on the very same piece of line during the search and rescue operation undertaken to find Charlie.

…

We have the technology to comply with the Dingell Act, shouldn’t the Forest Service mandate, just like we do eight-inch-high leather boots or Nomex, that wildland fire personnel have on a personal tracking device while on the fire line?

…

What is the protocol to determine that a wildland fire responder is missing? What is the protocol to find a missing wildland fire responder? Should there be a national standard to follow to reduce confusion?

…

What is the protocol to obtain notification information for our employees? What is the protocol for notifying fallen employees’ next of kin? Should there be a national standard to follow to minimize confusion and disorganization?

…

CAL FIRE and many other organizations have standard and required emergency notification forms that are available electronically to select individuals.

All articles on Wildfire Today tagged wildfiretoday.com/tag/el-dorado-fire/