#1 CANADIAN NATIONAL BESTSELLER • WINNER OF THE BAILLIE GIFFORD PRIZE FOR NONFICTION • SHORTLISTED FOR THE HILARY WESTON WRITERS’ TRUST PRIZE FOR NONFICTION • FINALIST FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK AWARD IN NONFICTION • ONE OF THE NEW YORK TIMES’ TOP TEN BOOKS OF THE YEAR

A stunning account of a colossal wildfire, and a panoramic exploration of the rapidly changing relationship between fire and humankind from the award-winning, best-selling author of The Tiger and The Golden Spruce.

In May 2016, Fort McMurray, the hub of Canada’s petroleum industry and America’s biggest foreign supplier, was overrun by wildfire. The multi-billion-dollar disaster melted vehicles, turned entire neighborhoods into firebombs, and drove 88,000 people from their homes in a single afternoon. Through the lens of this apocalyptic conflagration — the wildfire equivalent of Hurricane Katrina — John Vaillant warns that this was not a unique event but a shocking preview of what we must prepare for in a hotter, more flammable world.

Below are two reviews of Vaillant’s book, from two well-qualified writers, one in Canada and one in the U.S., written from two divergent perspectives yet reaching similar conclusions and opinions about the book.

How Fort McMurray’s wildfire became the devil of our own creation

By

ALBERTA, CANADA: Fort McMurray helped fuel its own demise and serves as a heavy-handed lesson in irony. Kind, surreally hard-working Albertans never dreamed of such payback.

The best book of the year is easily Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast, and not just because the planet spent most of 2023 in flames. Canadian author John Vaillant’s story, which begins with the 2016 fire that destroyed most of Alberta’s Fort McMurray, presents modern fire as a force of nature so implacable, so malevolent, that it might as well be the devil himself.

Like babies who can’t consciously recall trauma, Canadians seem to have forgotten that terrible summer, an odd form of self-defense. Vaillant’s magic is describing this new kind of fire, the unstoppable kind. He uses the word “infandous,” meaning a thing too horrible to be named or uttered. Recall for future use.

Infandous fire will haunt us until we change course on using fossil fuels. As we are seeing with COP28, it’s too late now.

Canada contains 10 percent of the world’s forests. It was once charming to sigh about Canada being an inveterate hewer of wood and hauler of water. But as global heating advances and fires pop up worldwide, the presence of wood endangers humans (and vice versa) and water becomes merely unhelpful.

The only thing that could be done when a distant wee fire got noticed by somebody on May 1 2016 at 4 p.m. was to watch aghast as the thing blew up in hot weather, worsened by drought and high winds. Spraying, soaking, or even waterbombing the blaze was pointless.

Like so many built places, Fort McMurray was in crossover territory, on the border between city and forest — and that’s where trouble lives. Much of it contains black spruce, a tree firefighters refer to as “gas on a stick.” Fire spreads almost instantly with embers shooting into the air like a cloud of kamikazes or a swarm of drones.

Vaillant’s story is plot-driven. Humans found fossil fuel and, hungry for the last dollar-drop, they found a use for Alberta’s tar. It’s not even “bitumen,” Vaillant points out, it’s “bituminous sand. It is to a barrel of oil what a sandbox soaked in molasses is to a bottle of rum.”

When fire arrives, “houses stop being houses. They become, instead, petroleum vapor chambers.” I will underuse the phrase “what made things worse” but technology made the horror more visible.

Sensors, nanny cams, CCTV, and central control mechanisms captured the sight of steel-beamed, 45-tonne homes vanishing. “Fully there, totally normal, to fully gone was five minutes,” one firefighter said. Wait until Vaillant introduces “fire tornadoes,” fires so huge they have their own weather systems.

“Fire Weather” is beautifully handled, full of that rare and valuable quality in non-fiction, context. A New York Times reviewer didn’t like this, bemoaning Vaillant’s unnecessary history, fancy philosophical wanderings, and “climate science, activism, and denialism.” This is exactly the kind of narrow American thinking that created climate change — that there are only individual narrowly defined stories rather than collective ones.

Climate change in the Petrocene Age is the most collective story ever told, Vaillant says, and certainly the biggest story since the Permian-Triassic Extinction Event 250 million years ago, which scientists call “the worst thing that’s ever happened.” And we did it to ourselves. What a species.

Reprinted with permission.

Twitter: @HeatherMallick

Heather Mallick is a staff columnist with the Toronto Star whose subjects range widely. She has published two non-fiction books — a diary and an essay collection — and has worked for CBC.ca, the Globe and Mail and other media. With a BA Hons and MA in English Literature from U of T plus a Ryerson journalism degree, she writes with courage and candour, and is an accomplished public speaker.

AMAZON CANADA

AMAZON CANADA

AMAZON U.S.

AMAZON MEXICO

Burnout

By Brian Ballou, Retired PIO

FIRE WEATHER: A true story from a hotter world

John Vaillant, copyright © 2023

Published by Alfred A. Knopf, New York

Fire Weather is the story of the Fort McMurray Fire and several other wildfires that attained heroic size in the past 30 years. But it is mostly about climate conditions that have created the perfectly cured fuels which are enabling wildfires to burn uncontrollably and attain immense sizes. It’s a very well-written book and is likely of interest to anyone in the fire service, wildland or municipal, regardless of country. The scope is huge, the story is sad, and the ending isn’t very nice.

The author, John Vaillant, was born in the U.S. but lives in British Columbia. Fire Weather is his fourth book and last month it received the Baillie Gifford Prize for Nonfiction. He has also written articles for The New Yorker, The Atlantic, National Geographic, and Outside magazines.

He clearly went all out in researching what has been written about wildfire and climate change, and interviewed many people who were intimately affected by the fires he writes about in this book. The result is impressive in scope, provocative, and disturbing. This is not bedtime reading.

Fire Weather launches right into the heart of the Fort McMurray Fire, writing “Choices that day were stark and few: there was Now, and there was Never.”

This sums up what firefighters and residents faced in early May 2016, when a wildfire overran the city of Fort McMurray, located in the boreal forest of northeast Alberta. It was unremarkable in this era of megafires — marked by wildfires with stunningly rapid growth, and which have become virtually unstoppable despite relentless suppression efforts from air and ground. However, 100,000 people lived in Fort McMurray, and on May 3 everyone was ordered to leave.

A significant problem was the options for escape. There were two. The road north ended in 30 miles at Fort McKay. The other was the highway that headed south, AB-63S, which, after four hours of driving, led one to the city of Edmonton. There were other small towns to the south but the problem was the fire. The Fort McMurray Fire originated southeast of the city of Fort McMurray and the wind was blowing toward the northwest. The highway going south was blocked, so residents were advised to go north.

This was a decision made by firefighters and emergency management officials after it became clear that efforts to contain the fire on any flank were unsuccessful. “Even if your equipment and manpower are inadequate to the task at hand, even if your adversary is disintegrating entire houses like a Martian death ray, your duty is to somehow stand between it and the citizenry and infrastructure you’re charged with protecting,” writes Vaillant, following his conversation with firefighter Lucas Welsh.

“It was chaotic and it was personal,” Welsh said. “I love this city. It’s my home and that was my neighborhood; my kids and my wife were five hundred yards away from me and evacuating.”

Firefighters were seeing homes go from ignition to complete destruction in five minutes’ time. Crews didn’t know which way to turn. There wasn’t any anchor point. “A lieutenant named Damian Asher compared these frantic efforts to cats chasing a laser pointer.”

While the firefighters chased the conflagration from neighborhood to neighborhood, fire and emergency managers faced the fact that the core problem was the weather. The forecast called for temperatures in the high 80s. “This wasn’t just a little bit warmer than normal — it was almost 30 degrees hotter than the average high for that time of year. Meanwhile, the forecast for relative humidity — 15 percent — was also record-breaking for that date; 15 percent humidity is not typical of the boreal forest in May; it is typical of Death Valley in July.”

“Given the long-term forecast,” writes Vaillant, “this fire could burn as long as the fuel held out, and in these conditions, the boreal forest was nothing but fuel.”

The forest in this part of Alberta is composed of aspen, poplar, and black spruce. Fort McMurray is a city within the wildland/urban interface where just a few steps beyond a home on the edge of town was a “virtually limitless expanse of dog-hair forest and muskeg — moose and beaver country that favors the amphibious and well insulated, and discourages casual exploration. Once beyond the tenuous membrane of suburbia, you were bushwhacking — all the way to Buffalo Head Prairie, two hundred miles to the northwest.”

It probably isn’t coincidence that Vaillant chose the Fort McMurray Fire as the keystone incident in Fire Weather — the city exists because of the oil sands mine and the bitumen extraction plant located right next to Fort McMurray.

Vaillant wastes little time underscoring the irony behind an unstoppable wildfire consuming a city that was built to serve the bitumen extraction industry. Bitumen “is a kind of degenerate cousin to crude oil, more commonly known as tar or asphalt. Surrounding Fort McMurray, just below the forest floor, is a bitumen deposit the size of New York State.” Extracting bitumen is one part of the international petrochemical industry that, decades earlier, authored definitive research papers that precisely predicted the continued warming of the planet largely due to the burning of fossil fuels.

The people mining the fossils and creating the fuels clearly chose to ignore their own research and continued making fuel for internal combustion engines and other products, such as the stuff plastic is made from.

Wildfires in the boreal forest were not unusual for much of Canada’s history, wildfire being a natural agent of change. But really, really big ones were a late-20th-century-to-early-21st-century phenomenon. And it wasn’t unique to North America. Huge fires in boreal forests had blackened millions of acres in Siberia — and Alaska. Elsewhere on the globe, in non-boreal landscapes, vast wildfires burned across Australia, South Africa, Portugal, France, Greece, and Italy. And the United States, mostly in the arid West.

Clearly, something new and different and very dangerous had overtaken much of the world. Call it Global Warming or climate change, and the age in which this is occurring will be called the Petrocene or the Pyrocene. “One among many ways to quantify these changes is through fire behavior: now, virtually every year, on every continent where anything grows, records are being broken for ambient temperature as well as for acres burned and homes destroyed,” writes Vaillant.

To solidify his argument about the violence the new fire environment can present, Vaillant turns to the Carr Fire, which burned near Redding, California in 2018. This part of Fire Weather reads like something from the Old Testament.

“In the rising light of dawn was revealed the aftermath of an atmospheric tantrum so violent it looked as if the Hulk and Godzilla had done battle there,” writes Vaillant of the aftermath of a fire tornado. “A pair of hundred-foot-tall steel transmission towers were torn from their concrete moorings and hurled to the ground. … Trees were torn limb from limb. In the branches of those that survived, where plastic bags might flutter, 10-foot pieces of sheet metal roofing were twisted like silk scarves. A camshaft, a flywheel, a kitchen sink, an oven door, and countless other objects were scattered through the charred forest. There was no glass anywhere. Grass, bark, and topsoil were gone.”

“Nothing, no matter how sturdy or how small, was left intact. Even the stones were broken.”

This is not breaking news for people intimately involved with fire management in the 21st century. But some may have need for further understanding about how this new and dangerous environment was created. Fire Weather does this and merits a look by those seeking answers. But don’t expect a happy ending.

Brian Ballou retired after 20 years with the Oregon Department of Forestry. He was a PIO and fire prevention specialist, and was stationed for 8 years at ODF’s headquarters in Salem and 12 years at the Southwest Oregon District headquarters in Central Point. For 7 of those years, Ballou was a lead information officer on one of ODF’s incident management teams. In 2015 he received a Bronze Smokey award for his service to wildland fire prevention in southwest Oregon.

Prior to joining ODF, Ballou was a seasonal firefighter with the U.S. Forest Service, working on the Willamette, Siuslaw, Winema, and Rogue River national forests. He was also the founding editor of Wildland Firefighter Magazine.

This animation is showing the fire spreading in Fort McMurray, Alberta from May 1st to 20, 2016. Credit: @NRCan. pic.twitter.com/cLea70sSOQ

— Canadian Space Agency (@csa_asc) May 27, 2016

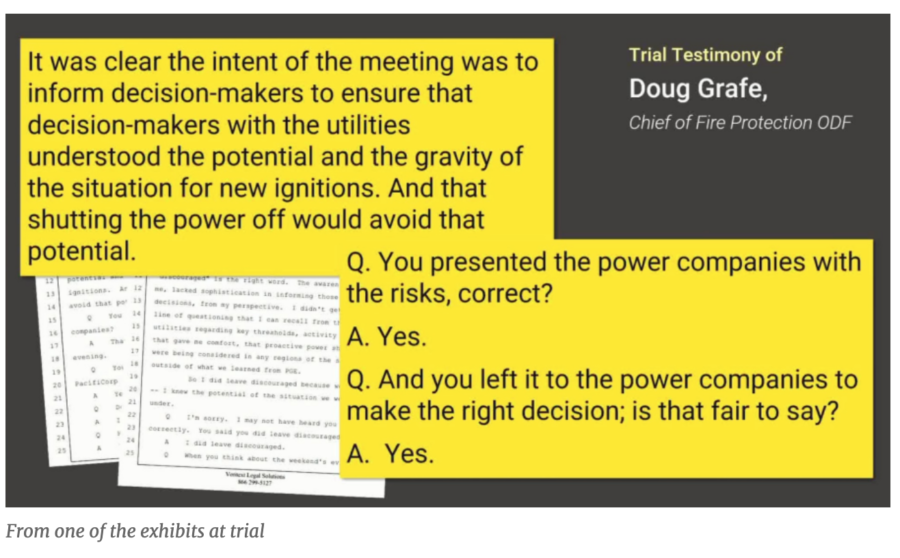

She said some Maui agencies have cooperated with investigators, but that subpoenas were issued to the Maui

She said some Maui agencies have cooperated with investigators, but that subpoenas were issued to the Maui