FROM 2018

News and opinion about wildland fire

Speaking of fireworks safety over the Independence Day holiday, James Duff with the City of Orinda, California tipped us off earlier this month to this outstanding little 2021 PSA from Lubbock, Texas. We are entertaining nominations for award-winning fireworks messaging, and there is a prize involved, so please nominate your “July 4th Hot PSA” from a fire agency, government agency, or NGO related to fireworks use and fire safety.

Write at least one sentence about who it is and where it is, add the link, and post it in the comments below.

Meanwhile, enjoy this little gem from Texas.

Fire Chief Buddy Peratt said the fuel load of dry vegetation this year increases the risk of wildland fires, particularly those started by fireworks.

In Apple Valley all fireworks are illegal

“It’s important that people understand that all fireworks, including those classified as ‘safe and sane,’ are illegal in Apple Valley,” Fire Inspector Jennifer Alexy told the Victorville Daily Press.

She said information about illegal fireworks is important for all residents, especially those who’ve recently moved to Apple Valley. “Sometimes people move here from down the hill or other areas, and they don’t realize that fireworks are illegal,” Alexy said. “They start using fireworks, unaware of the potential danger.”

How citations are issued: The Apple Valley Fire Protection District uses a “contactless citation process” in which citations are delivered by district personnel directly to the offender in person or by mail. An administrative citation is $1,000. If a fire official has proof of a renter’s possession or use of fireworks, the district can also cite the property owner.

“We’ll gather the information and send the owner a citation via certified mail,” said Alexy. “We’ll make sure owners are responsible for their tenants.”

QR code to report fireworks: Apple Valley Fire uses a QR code to report the possession, sale, or use of fireworks in town. “If someone calls our office to report fireworks during the weekend,” says Alexy, “we may not get the message until Monday morning. The QR code allows us to get the information right away.”

Fireworks are literally explosively loud, panicking pets and many veterans, and can mean trauma for people with with sensory issues. The debris and chemicals left over from fireworks can harm the environment, pollute the air, and leave behind hazardous waste.

Back in 2000 at least 10 fires were started on and around Mt. Rushmore during fireworks displays. Perchlorate, which is now in the water at the national park after numerous fireworks shows held there, has been linked to fetal and infant brain damage — 11 fireworks shows between 1998 and 2009 contaminated the water at the memorial. The fireworks explosions left perchlorate on the ground, and it worked its way into the water table. In 2016 a USGS report showed that a maximum perchlorate concentration of 54 micrograms per liter was measured in stream samples at Mt. Rushmore between 2011 and 2015 — about 270 times higher than in samples collected from sites outside the memorial.

Wildfires: During those 11 shows at least 20 documented wildfires were ignited by fireworks in the middle of the wildfire season.

Garbage: The trash dropped by the exploding shells onto the National Monument and the forest can never be completely picked up. Left on the ground are unexploded shells, wadding, plastic, ash, pieces of the devices, and paper — that can never be totally removed from the very steep, rocky, rugged terrain.

NOTE: Bill Gabbert, who founded this website and ran it for many years, was the fire management officer at the Mt. Rushmore site during some of that time.

Oklahoma is the testing ground for a new wildfire system that uses local National Weather Service (NWS) forecast offices to quicken alerts sent to nearby communities.

The alert system software, called “Wildfire Analyst,” was created by wildfire technology company Technosylva. Its promising results were backed up at a recent U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology hearing.

Oklahoma State Forester Mark Goeller explained the system to representatives while testifying at the hearing. He said the software, using NWS data and local emergency management warning systems, significantly reduces fire warning times by predicting a wildfire’s potential spread from the ignition point.

“The fire warning was issued in just six minutes on a recent wildfire occurring in a heavily populated wildland/urban interface area in the Oklahoma City metro,” Goeller said. “Oklahoma is the first state in the nation to use this system. Using our legacy process, it often required approximately 90 minutes to issue the fire warning.”

The Wildfire Analyst software has three core applications, according to Technosylva. The software’s “FireSim” application was the main tool Goeller referred to during the hearing. The application generates real-time fire spread predictions and supports wildfire planning through “what if” scenarios. The software’s other two applications, “FireRisk” and “FireSight,” predict wildfire risk days through forecasts and calculate risk reduction, respectively.

The state’s goal to overhaul its wildfire alert system started after its 2005-06 season when numerous fires burned in Texas and Oklahoma, Goeller said during the hearing. The fires resulted from prolonged drought and strong winds and killed 25 people and 5,000 head of cattle — and destroyed hundreds of homes, according to the Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center.

Soon after that catastrophic season, the “Southern Great Plains Wildfire Outbreak Group” came together, including members of the Oklahoma Forestry Services, Texas Forest Service, and National Weather Service forecast offices. The partnership spawned from that group eventually led officials to look specifically at how weather dynamics did and could affect the states’ wildfire response.

“The things that I would emphasize as the lessons learned are for other states’ forestry agencies and local emergency management agencies to get to really working closely with their National Weather Service forecast offices,” Goeller said. “Look at the model we apply in Oklahoma, look at the process we went through … the research that went into what affects our weather systems would absolutely be employable in other places.”

Oklahoma is the testing ground for a new wildfire system that uses local National Weather Service (NWS) forecast offices to quicken alerts sent to nearby communities.

The alert system software, called “Wildfire Analyst,” was created by wildfire technology company Technosylva. Its promising results were backed up at a recent U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space and Technology hearing.

Yet another destination known for its skiing and snowy winters will be forced to contend with growing wildfire severity and frequency.

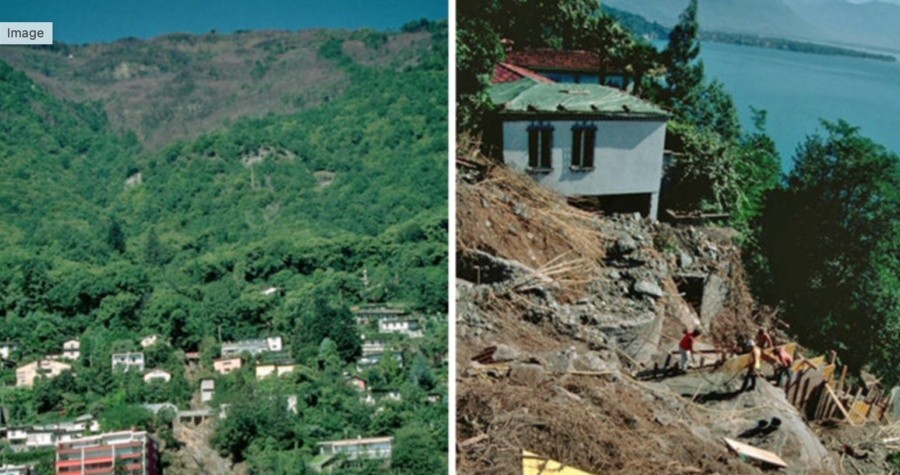

The Alps, Europe’s largest mountain range and a world-renowned skiing destination, and the Alpine Foreland, a deep trough in southern Germany at the edge of the Alps, have both enjoyed minimal wildfire danger thanks to abundant winter snowfall and temperate summer conditions. But that will change by 2040.

A study published in Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences (NHESS) used climate models to forecast fire risk for the two locations and others from 1980 to 2099. Researcher Julia Miller used the Canadian Forest Fire Weather Index (FWI) as a fire danger indicator.

The research forecasted a likely increase in wildfire danger in temperate areas through the 21st century, with fire danger increasing to high even in regions where it is very low today. The results displayed a continual trend of worsening wildfire danger in the Alps and Alpine Foreland, with the climate change trend exceeding natural variability in the late 2040s. The excess would likely have happened earlier if not for the area’s current low wildfire danger.

These areas are expected to see what’s today considered a “100-year” fire event every 30 years by 2050 and every 10 years by the end of the century.

“Alterations in these variables are projected to more than double the frequency of occurrence of extreme fire weather until the end of the 21st century … and increase the duration, severity, and spatial extent of fires,” Miller said. “Due to climate change, fire weather and hence the likelihood of fire events are projected to increase in several regions of the world – including historically less fire-prone areas – in the future.”

A study posted on PreventionWeb indicates that fires in the Alps will increase because of growing intensity of drought periods and heat waves — and the increasing fire hazard resulting from rural abandonment and more recreational activities.

Alpine communities, such as the previously mentioned Canadian community of Whistler, may see this as a hard pill to swallow. The lack of historical fires in the area means local people also lack an established “culture” for living with fires, according to Switzerland’s University of Bern. Researchers there are currently working to identify the wildfire risk awareness of communities throughout the canton of Bern and determine the best approaches for specific groups in the area.

“Based on scientific findings, the project aims to develop optimized and/or new communication strategies and materials for implementation,” the university said. “These can promote behavioral changes regarding forest fire risks, thus helping to prevent such fires.”

A longstanding wildfire safety collaboration between the Tonto National Forest and Arizona’s Gila County officials needs updating. The county began collaborating with the USFS and local fire districts back in 2006 when it installed 14 water tanks, bladders, and storage systems in helicopter-accessible areas on the forest. The intent, according to a recent Gila County Board of Supervisors meeting, was to put fires out as soon as they were detected in the Rim Country area near Payson. The water sites were positioned where helicopter turnaround time would be less than five minutes.

But those water systems are now falling apart. Gila County Emergency Services Coordinator Carl Melford told the Board of Supervisors that the average lifespan of a water bladder is five to seven years, and many of the sites have old bladders with deteriorating water storage tanks.

Melford hopes to use a $609,000 congressionally directed earmark grant through the USFS to fix the deteriorating system. The funds would have to be matched from Gila County for a total of $1.2 million.

“This funding provides the opportunity for the evaluation and purchase of new water tank storage systems to replace the dilapidated tanks and old bladders and to hire a qualified contractor to transport and install 56 tanks of 5000-gallon capacity at the 14 locations,” Melford said in his proposal to the board. “This will increase the capability of fire suppression efforts, which is vital to the protection of Gila County residents’ life and property in areas prone to wildfires.”

Bids for the project are due by May 14, just in time for what used to be the start of Arizona’s wildfire season from late April to the beginning of monsoon in June. That “season,” however, looks to mostly be a thing of the past as wildfires burn 100 days more than they did 50 years ago.

“We really don’t say we have a ‘fire season’ because we can have activity throughout the state year-round,” Arizona Department of Forestry and Fire Management spokesperson Tiffany Davila told the Arizona Republic last year. “We can see fire activity increase during the end of April, beginning of May.”

The Tonto National Forest’s most recent wildfire, the Valentine Fire, started on August 16 last year, nearly caused evacuations, and burned nearly 10,000 acres.