In 2018 Rick Stratton, a USFS fire planning program manager for the R6 Regional Office in Portland and Pyrologix provided a Quantitative Wildland Fire Risk Assessment for communities most at risk in the Pacific Northwest — and he listed the top 25.

Six years later he compared that assessment with what had actually happened, and 18 of the 25 communities had recorded significant/catastrophic wildland fires. His assessment illustrates a rapidly evolving wildland fire environment, in which entire communities are at risk. Below are some of Stratton’s slides.

How do interface disasters occur? Jack Cohen‘s work on wildland/urban interface fires demonstrated that in the beginning, the set-up for a disaster fire includes extreme fire conditions — much of which has been widespread across the West over the last decade or more. Abundant dry fuels, fire-friendly weather such as drought, extreme heat, low humidities, and high winds all contribute to a landscape ready for a fire disaster.

To that setting is added both wildland fire (with rapid spread) and urban fire — which includes multiple simultaneous ignitions and residential areas in which fire spreads from house to house to house, complicated by non-vegetation burning of cars, fences, decks, garages, stacked firewood, and often-hazardous materials typically found on interface industrial properties, workshops and garden sheds, or even gas stations. Frightened residents trying to evacuate on limited access routes, often with uncoordinated communications and plans, simply multiply the crisis.

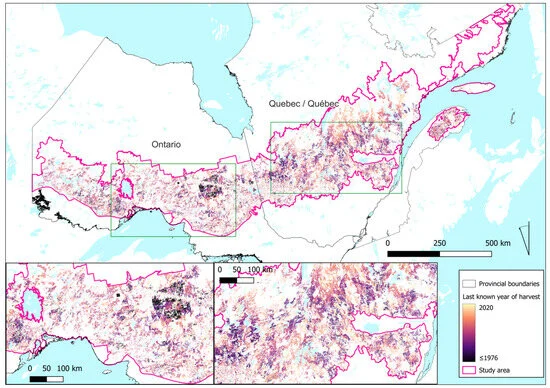

Pacific Northwest risk map: Clearly illustrated here is the band of interface-populated communities that runs down from the northeast corner of Washington to the southwest corner of Oregon — adjacent to and in forested areas.

Unlike the larger metro areas (Seattle, Portland), these communities are surrounded by rural and forested land, and consist mainly of smaller communities with limited suppression resources, and sometimes challenging water supply or prevention resources.

… and … 6 years later:

Only a few of those ranked community exposure locations were NOT burned by a large interface fire. Ellensburg, Washington, suffered multiple fires, as did Spokane, Grants Pass, and Chelan.

A Western Region Co-Chair for the Wildland Fire Cohesive Strategy, Joe Stutler worked 35 years with the U.S. Forest Service. Since retiring, he’s worked for Northtree Fire International and as senior forester with Deschutes County for 8 years. He has worked as a hotshot, smokejumper, district and forest FMO, district ranger, law enforcement officer, and regional fire operations specialist for both R5 and R6. He put in 33 years as Type I and II Incident Commander and 6 years on National Area Command Teams. He has managed all-hazard and law enforcement assignments across the country and currently fills Command and General positions on Type 1 IMTs and Area Command teams.

Here are a few of Joe Stutler’s thoughts on these risk assessments: I am wide-eyed at the accuracy of Rick Stratton’s predictions and the big fires that followed in 2018-2022. Most of these high-ranking landscapes were in Fire Regimes 1 & 2, and those that have been burned by large intense wildfire have now reset to Condition Class 1. But what about those that remain in Condition Class 3, like here in central Oregon and other places in the U.S.?

The wildland fire environment is rapidly changing, and this slide deck shows that to be true. The question is, what can we in the business of helping people understand it actually do about it? The answer lies in collectively and strategically communicating these issues.

From my world, I immediately think about how the Cohesive Strategy has been affirmed by the Wildland Fire Leadership Council (WFLC) AND the President’s Wildfire Mitigation and Management Commission as THE strategic framework that can be applied at and by every level (federal, tribal, state, local, and NGOs) to address wildland fire challenges to make substantial, meaningful progress toward landscape resiliency, community resiliency, and fire adaptation — and a safer, more effective, risk-based wildfire response.

The part that stands out to me (apart from the obvious needs to increase the pace and scale of landscape resiliency treatments and address the different response approaches and needs of the “urban firestorm” probability) is the need for doubling down toward the CS goal of fire-adapted communities. The goal is described as “communities that are as prepared as possible to receive, respond to, and recover from wildland fire.”

This elevates the responsibility for preparedness to more than just our response as land management agencies and organizations, but to us as residents, responders, planners, emergency managers, governments, businesses, news outlets, and other organizations in communities. We each have a responsibility to think about what RECEIVING FIRE, RESPONDING TO FIRE, and RECOVERING FROM FIRE means to each of these community affiliates — and start heading down the path of preparation. These are ripe for defining within communities and providing suggestions for action. The definitions and suggestions will be different in every community, and we can organize and assist with these conversations, suggestions, and actionable solutions.

Many best practices have been applied and are underway across the West by all these entities, but the devastating destruction of entire communities over the last decade tells us that there is still much to do at the community level to prepare for wildland fire. Even today, many communities across the West — and for that matter east of the Mississippi — still do not realize that not only is the wildfire risk high, but there is also high likelihood of loss given the rapidly changing wildland fire environment. A changing climate (hotter, drier, windier conditions) alone is making “urban firestorms” a more prevalent reality, even in the East and South.

It’s clear that we need efforts toward all three goals of the Cohesive Strategy to make a difference and change the outcomes of wildland fire. Our vision is a good place to start — “To safely and effectively extinguish fire, when needed; use fire where allowable; manage our natural resources; and collectively, learn to live with wildland fire.” If we as individuals are truly learning to live with wildland fire, we must consider what that looks like in the face of the research and outcomes that Rick Stratton shares and then apply the Cohesive Strategy for better fire outcomes.

Ignoring our responsibility to learn to live with wildland fire is a choice. And we now know what the outcomes of that are.