The map shows lightning detections during the 48-hour period ending at 10 a.m. MDT July 9, 2020. The red dots are the oldest.

Category: Uncategorized

COVID takes us back to our fire suppression roots, for now anyway

The precautions wildland firefighters have to take to reduce or prevent spreading the dangerous COVID-19 virus has affected the suppression of wildfires. The new procedures include keeping crews together and as isolated as possible, transporting fewer firefighters in each vehicle, avoiding fire camps when possible, sanitizing everything, physical distancing, reducing travel, and limiting contacts and interactions. These policies may reduce the efficiency and output of crews.

Another effect of the pandemic is the re-adopted strategy from 110 years ago of putting out almost all new fires as quickly as possible. Managing a fire for “resource benefits”, formerly called “let burn”, can result in huge fires that burn for months, tying up hundreds of firefighters. They produce smoke that can be especially harmful to those with lung damage caused by COVID.

Below is an excerpt from an article by Jeanne Dorin McDowell published July 7, 2020 in Smithsonian Magazine.

With COVID, firefighting is hearkening back to the more-antiquated style. For example, firefighters will respond quickly to suppress small fires quickly rather than letting them burn, using local resources instead of bringing in firefighters from other areas. Controlled burns, fires set intentionally to eliminate dead growth and pave the way for new healthy growth, will be reduced if not canceled for the 2020 fire season because the accompanying smoke can seep into surrounding communities and harm individuals who have acquired the COVID-19 virus.

“We need to go back to the original Smokey Bear model, for this year anyway,” says California state forester and fire chief Thom Porter, director of CAL FIRE (California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection). “While we are in the COVID pandemic, we have to reduce smoke impacts to communities from long burning wildfires, even in exposure to our firefighters. We have to keep fires small. Yes, it’s a throwback and not what I want in the future. But it’s something we need to do this year.”

Towards that end, aerial firefighting will be beefed up and helicopters added to fleets to douse fires with flame retardant or water in advance of firefighters trekking into locations to fight wildfires. Says the Forest Service’s Hahnenberg: “We will mount aerial attacks, even in remote areas where fires might have been allowed to burn in the past, to reduce risks to ground crews and the public from smoke that could make them more vulnerable to severe COVID-19 illness.”

This is the first time I have seen a quote from a high-ranking person in the U.S. Forest Service saying out loud, so to speak, that they were beefing up the number of fire aviation resources due to the pandemic.

Wildland firefighters’ invisible injuries can be life-threatening

A real-life example after the line of duty death of a fellow firefighter

During his 14 years working for the Bureau of Land Management as a wildland firefighter, a fire that Danny Brown responded to on July 30, 2015 changed his life in ways that most of us cannot fathom. Mr. Brown was one of the first to find the burned body of his friend David Ruhl who was entrapped and killed during the initial attack of the Frog Fire in northern California.

An excellent article by Mark Betancourt in High Country News describes the upheaval that occurred in Mr. Brown’s life, how he tried to deal with it, and how the government’s system for treating on the job injuries failed.

Here is a brief excerpt:

The trauma Brown sustained that day could happen to any wildland firefighter. It drove him out of the career he loved and the community that came with it, and to his agony it limited his ability to support his wife and their three children. He was eventually diagnosed with chronic PTSD — post-traumatic stress disorder — and in his most desperate moments, he thought about taking his life. Adding to his suffering was the feeling that he had been abandoned by the government that put him in harm’s way.

A number of people bent over backwards trying to help Mr. Brown receive the professional help he badly needed, including a friend, a supervisor, the Wildland Firefighter Foundation, and Nelda St. Clair, a consultant who coordinates fire-specific crisis intervention and mental fitness for federal and state agencies.

Federal agencies that employe wildland firefighters (but call them technicians) hire them to perform a hazardous job. A percentage of them in the course of their career will be involved directly or indirectly with a very traumatic event. Many of them will power through it with no serious effects, at least outwardly. But others will suffer unseen injuries after having performed their duties.

These federal agencies do not have an effective system or procedure for helping their employees heal from chronic PTSD — post-traumatic stress disorder — incurred while on the job. Untreated, chronic PTSD can lead to suicide.

Ms. St Clair tries to keep track of how many wildland firefighters take their own lives each year. Her unofficial tally suggests as many die by suicide as in the line of duty.

I can’t help but think that if the job title of these “technicians” was instead, “firefighter”, it might be easier for the hierarchy to understand, and get them the professional support some of them so desperately need. Range Technicians have different job stresses than wildland firefighters. In some cases chronic PTSD is an issue of life and death, not something we can keep ignoring.

If you are a firefighter of part of his or her family, you need to read the article in High Country News. If family members recognize the symptoms it could be helpful.

If you are in an influential position in the federal land management agencies you need to read the article. Look at the firefighters in the photo above who were attending the memorial service for Mr. Ruhl. Do what you can to ensure that no other employees are forced to suffer like Mr. Brown and no doubt others, have.

If you are a federal Senator or Representative, you need to read the article. Then introduce and pass legislation so that other “technicians” do not have to suffer like Mr. Brown.

Help is available for those feeling really depressed or suicidal.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255. Online Chat.

- Anonymous assistance from the Wildland Firefighter Foundation: 208-336-2996.

- National Wildland Fire and Aviation Critical Incident Stress Management Website.

- Code Green Campaign, a first responder oriented mental health advocacy organization.

- Would you rather communicate with a counselor by text? If you are feeling really depressed or suicidal, a crisis counselor will TEXT with you. The Crisis Text Line runs a free service. Just text: 741-741

Rain followed the fireworks at Mount Rushmore

Almost one-fifth inch fell shortly after the fireworks ended

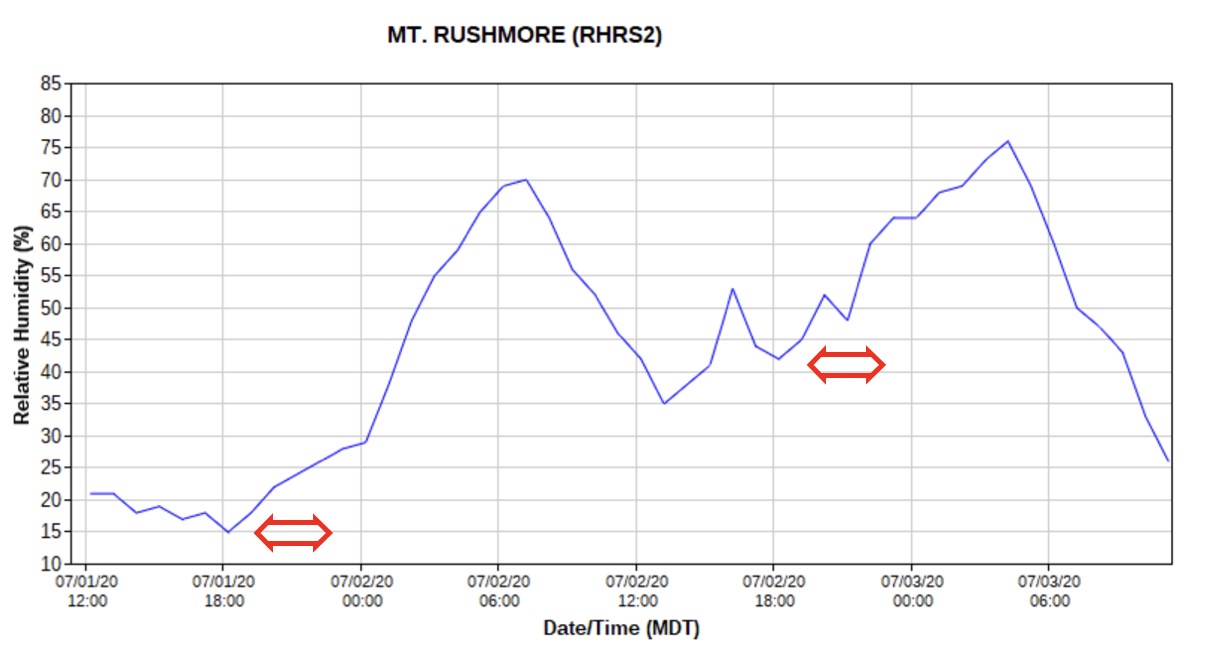

Rain fell shortly after the July 3 fireworks show at Mount Rushmore. The official Remote Area Weather Station at the Memorial recorded 0.17 inch between 10 p.m. and 12 p.m MDT. In less than an hour the relative humidity went from 44% to 86%. The rain was followed 24 hours later with another 0.03 inch at 11 p.m. MDT July 4.

“We had crews monitoring on the mountain last night and they are still working today,” a spokesperson for the Incident Management Team mobilized for the event, Erin Hilligoss-Volkmann, said Saturday afternoon July 4. “There have been no reports of fires as of yet. We are continuing to monitor and will have more information soon. As you’re likely aware, there was a pretty significant rain event following the fireworks event.”

If any fires were started by burning embers from the explosions they likely would have grown very slowly in the sparse fuels remaining two months after the Memorial was treated with a prescribed fire. The rain falling within minutes after the program ended accompanied by very high humidity would have made it difficult for a new fire to grow or avoid extinction.

In addition to the 27 fires started at Mount Rushmore by previous uses of fireworks from 1998 to 2009, many of those concerned about the environment have additional concerns:

- Putting even more carcinogens in the water. Studies from 2011 to 2015 by the USGS found 270 times more perchlorate in the water at Mount Rushmore than in the surrounding area and determined that it likely came from fireworks. The Centers for Disease Control says high levels of perchlorate can affect the thyroid gland, which in turn can alter the function of many organs in the body. The fetus and young children can be especially susceptible.

- The trash can never be completely picked up. Left on the sculpture and in the forest are unexploded shells, wadding, ash, pieces of the devices, and paper; stuff that can never be totally removed in the very steep, rocky, rugged terrain.

Fire behavior analyst calculates the probability of embers from Mount Rushmore fireworks igniting wildfires

Fireworks are scheduled for Mount Rushmore after 9 p.m. MDT July 3.

With a large fireworks show slated to be carried out this evening over the Mount Rushmore sculpture and the surrounding pine forest, I solicited a fire expert, a Fire Behavior Analyst, to develop a forecast to predict the danger presented by the burning embers that fall to the ground.

One of the primary reasons the fireworks at Mount Rushmore have not been displayed since 2009 is that during the 11 years they were used, between 20 and 27 fires were ignited. In 2000 one of the fires that started that night burned into the next day, grew to several acres, and required a 20-person crew and a helicopter to bring it under control. There were two injuries; one person had to take time off from work to recover.

During the early years of the events as the National Park Service Fire Management Officer for Mount Rushmore, I helped develop a Go/No-Go checklist of criteria that had to be acceptable to allow the shows to occur. It included items such as obtaining a Spot Weather Forecast from the National Weather Service, wind speed, qualifications of firefighting personnel, and the Probability of Ignition (PI or PIG). The PIG is the chance that a burning ember or firebrand will cause an ignition when it lands on receptive fuels. The beautiful fiery streaks you see after every explosion of fireworks contain hot embers, some of which after landing on the ground can start a fire.

I still have in my files a letter the NPS Midwest Regional Office sent to the staff at Mount Rushmore after the 17 fires in 2000. It directed that in the future the maximum allowable PI be reduced from 30 percent to “less than 10 percent.”

The NPS will not release this year’s Go/No-Go checklist or confirm if the PIG will be a evaluated, citing “security and safety concerns.”

Mike Beasely, a former wildland firefighter with the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service, is a trained and qualified Fire Behavior analyst. He is able to predict the spread of fires and is skilled in the science that influences how a fire burns.

Mike studied the weather conditions in the Mount Rushmore area and the weather recorded at a fire weather station at Mount Rushmore. Using algorithms and computer models, he predicts that if the fireworks begin at 9:15 to 9:30 as scheduled tonight, at that time the PIG will be 50 percent. In other words, about half the still burning embers created by the fireworks that hit the ground could ignite vegetation. Mike said that after 9:30 the PIG will drop throughout the night and would likely be 10 percent by 4 a.m. MDT on July 4.

One of the important factors to consider is the first ever broadcast prescribed fire that the NPS conducted at Mount Rushmore on April 29. The project reduced the amount of burnable vegetation on the forest floor, which decreased the amount of “receptive fuels” that could ignite if contacted by a burning ember. But depending on how deep the organic layer was before the prescribed fire, its moisture content, the residence time of the fire, needle cast in the last two months from the pine trees, and the fire’s intensity, it could be possible for fires to be ignited from the falling embers from the fireworks. If the burning embers fall in the footprint of the prescribed fire and ignite the remaining fuel, the resulting fire would likely burn slowly and at low intensity. In 2000 fires were ignited 1,200 to 1,300 feet north of the fireworks launch site.

Another caveat addressed by Mike: if prior to the fireworks a wetting rain occurs on Friday afternoon or evening, the one-hour time-lag fuel moisture resets to 30 percent and the fuel drying algorithm starts over, effectively making the PIG zero percent.

Below are excerpts from Mike’s eight-page analysis. You can download the entire document HERE.

Assumptions

- Uses weather record from Mt. Rushmore Remote Automated Weather Station (RAWS) #392603

- Uses day time fuel moisture reference tables (Appendix B), rather than night time tables (Appendix A), per NWCG guidance, despite fireworks being slated for 9:15-9:30 MDT

- Rain Caveat: If at any point prior to the fireworks, a wetting rain occurs, the 1-hr. TLFM resets to 30% and the fuel drying algorithm starts over, effectively making your PIG 0% (see Appendix D)

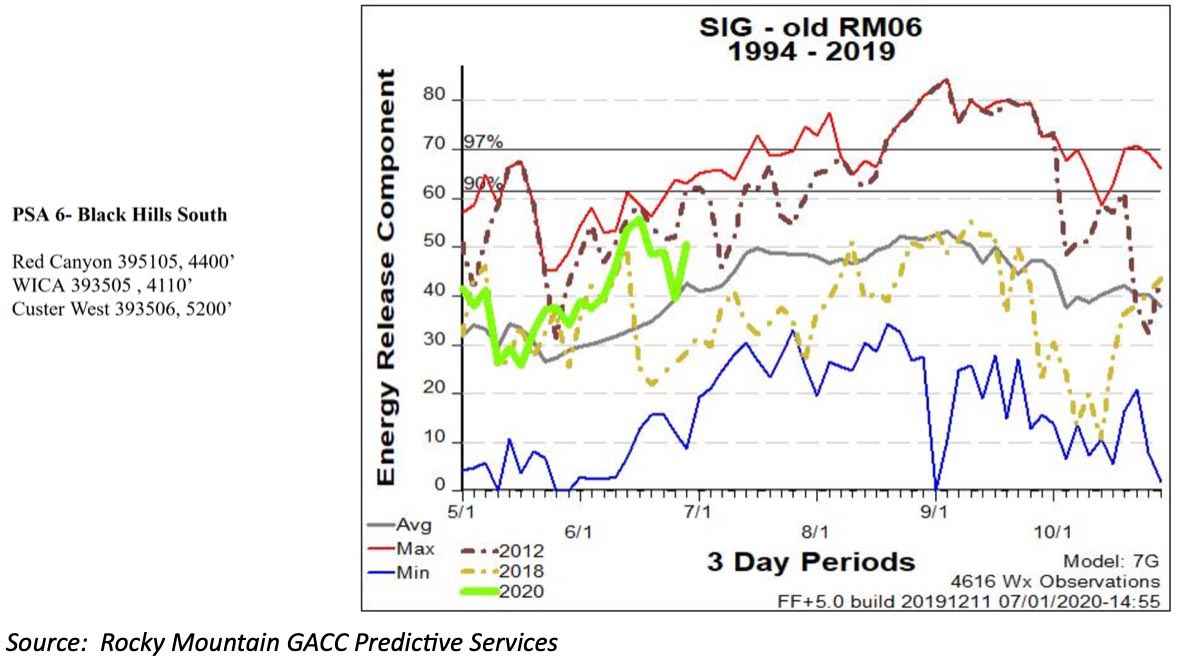

Climatology

The Black Hills and specifically the area around Mt. Rushmore are experiencing an above average fire danger as shown in the following ERC charts for the northern and southern Black Hills. While, well below historic maxima, this is consistent with the Moderate Fire Danger rating for the peak of the burning period forecasted for July 3rd. Wildfire Today has reported on the Moderate Drought level for the region as assessed by the Drought Monitor.

Inputs

The only two inputs for PIG are air temperature and 1-hr. time lag fuel moisture (TLFM). Both are highly variable with the daily diurnal cycle. The Mt. Rushmore RAWS data input daily has yielded the following fuel moistures predicted for mid-afternoon tomorrow immediately before the firework display. While not inputs for the PIG they are given as a general reference.

- 10-hr TLFM: 8%

- 100-hr TLFM: 9%

- 1000-hr TLFM: 12%

Recent Precipitation: The Mt. Rushmore RAWS received nearly eight tenths of an inch between June 28th and July 1st. That rain aided in the control of a nearby fire in Custer State Park, but there has been no subsequent precipitation.

There was precipitation around the Black Hills over the 24-hour period that ended at 10 a.m. MDT July 3, but it missed Mt. Rushmore. The NWS estimate below shows, over the past 24 hours scattered sites near Mt. Rushmore may have received as much as another half to three-quarter inches, but the gap shows over the Monument.

Below are the estimated temperature and relative humidity during the fireworks. Since we don’t have a site-specific weather forecast, we will use the more generalized NWS fire weather forecast and look at persistence over the past two dry evenings, understanding that the region is moving into a hotter, drier period.

The sister of one of the Granite Mountain Hotshots tells her story

In 2013, 19 of the 20 members of the crew were killed on the Yarnell Hill Fire

From Bill: June 30 marked the seventh year since 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshots were killed on the Yarnell Hill Fire south of Prescott, Arizona. Words can’t express how meaningful that event was — and still is — to the firefighting community. Our hearts go out to the friends and family members of the 19 firefighters.

With a different perspective on the impacts, we have an article published on Devon Herrera’s blog Coffee With a Question. Much of it is in the words of Taylor Caldwell, the sister of one of the Hotshots, Robert Caldwell.

06.30.2013

When I got a message from Taylor informing me she was ready to tell her story but needed help telling it, I was excited, then honored, then extremely intimidated, not only because I’d known and loved her brother since elementary school, but because the Yarnell fire that took 19 hotshots will forever be etched into Prescott’s history, and in our hearts.

“I just think it’s time,” she said. “The seven-year anniversary is coming up and I want to honor him.”

That’s right… seven years. I cannot believe it’s been seven years since the tragedy that would ultimately pull our community back together.

I told Taylor we would schedule a time to interview her, but she wanted to do things a little more unconventionally… I always admired her trailblazing spirit.

“So, I’ll probably talk your ear off for hours if we’re on the phone; do you think I can just record myself and send it to you?” she asked.

I’m all about collaborating in new ways, so of course, I didn’t think twice about it; this is Taylor’s story, after all, and I’m just privileged to be a vessel to share it with you.

So, without further ado…

“We called Robert, Buggy or Bug Man; he was born right outside of Pennsylvania on August 7th, 1989 – we were exactly 2.5 years apart and because of this, we always got a kick out of wishing each other a happy half birthday. My brother had the most infectious smile and laugh, which I can still hear to this day,” I watched her smile as she thought of it.

She explained how they would consider themselves best friends before siblings; that they did everything together.

“Robert helped our dad build a cabin out in Colorado when we were super young; he was always so good at putting things together… so active and wild, always living outside the lines. At a certain point, my dad took him bird hunting, then fly fishing just to try and keep him away from trouble. The attempt at sports was short lived… he was absolutely terrible… seriously, my dad tried to get him into everything, but he had about zero coordination.”

Our laughs hummed at the same time before I shared a story about Robert doing flips off the fence at our elementary school; he was always down for a dare. Oh, and yes, if you’re confused about how I’m chiming in now, we’ve incorporated an actual interview into this piece, to make sure we deliver the desired message.

Back to scheduled programming –

“You know something funny?” Taylor offered, “Robert had three dogs throughout his life, and he named each of them Hunter.”

“Easier to remember that way, I suppose. I’m sure more people wish it was that smooth when they transitioned relationships,” she raised her eyebrows as if to say, ‘you’re tellin’ me’ then repositioned her phone on the dining table.

“Something I don’t think a lot of people would know about my brother was his love of books. He was always, always reading. I actually have the book he was reading before he died… let me go grab it,” she got up and walked to her kitchen, coming back to show me a copy of ‘Scar Tissue’ by Anthony Kiedis – the lead singer of the Red Hot Chili Peppers. She told me he was a big fan of Ernest Hemingway, too; so much so that a lady in Maryland sent over an original copy of one of his books after he passed. It was called Farewell To Arms.”

“Maryland?” I asked…

“Yeah, my dad had a boat in Salisbury, Maryland and Robert would go live on it during the off season; he’d drive around town in my dad’s Porsche. I’m actually pretty surprised he didn’t total it, like this truck he and his friends flipped when they were 14. But again, as crazy as he was, and as much trouble as he caused, he cared so much about people. Oh, and he loved a theme party… any chance to dress up, he was in. It’s why we have our annual Bob-A-Palooza now… celebrating him just as he would want it.”

I smiled, recalling the time he helped me get ready at his house… I actually don’t even think we were going to a theme party, but he wanted me to dress up with him, so I did, and he even helped with my hair.

“As you could’ve guessed, Robert absolutely hated school. He had a mechanical mind so he wanted to be more hands on; he could fix just about anything which came in handy when the check engine light went off. So, I wasn’t surprised when he said he wanted to be a hotshot; he explained to me that he wanted to help people. He always wanted to help people… he had so much empathy. I remember when I came out as gay, Robert was my biggest advocate. He cried because he knew what a burden it must’ve been on me; he showered me with every bit of love, making sure I knew how much he supported me,” she fondly remembered while briefly looking down.

“Robert would always send me crazy pictures while he was out with his crew; pictures that didn’t even seem real, like the slurry bombers. He’d send me videos of him with the boys; they’d always play pranks and I could tell how deeply each of them loved each other. I also remember the picture he sent me of his burnt boots; it was the fire right before Yarnell. ‘T, look… I got so close, my boots melted,’ he wrote, and he truly wasn’t scared; he was more annoyed with the inconvenience of having to get new boots,” we both laughed again.

Continue reading “The sister of one of the Granite Mountain Hotshots tells her story”