Additional research finds evidence of a “fireproofing” effect on host trees from defoliation due to western spruce budworm outbreaks.

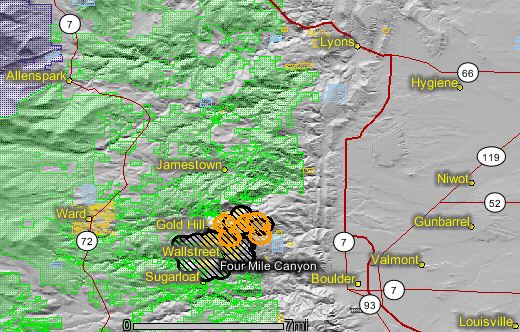

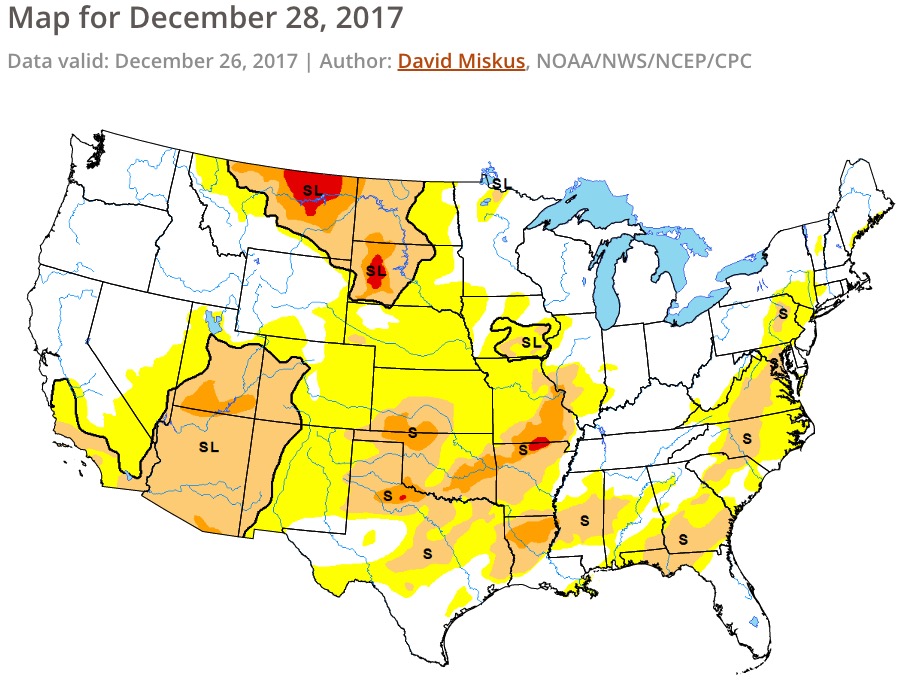

Above: Grand fir in Oregon defoliated by western spruce budworms. William M. Ciesla.

There is no dispute that severe outbreaks of western spruce budworm (WSB) and mountain pine beetle (MPB) in a forest have huge visual impacts. Many land managers have worried about more, larger wildfires and politicians have used it as an excuse for more logging.

But the commonly held belief that the effects will lead to higher intensity, more rapidly spreading wildfires has been disproven many times in the last eight years by scientists.

We first wrote about this issue in 2010 (Firefighters should calm down about beetle-killed forests) when some early research started to bring the facts to light.

The WSB and MPB attack trees very differently. The WSB defoliates the tree, consuming the needles and removing fuel from the canopy relatively quickly. The MPB kills the tree from the inside, leaving the dying “red” needles on the tree until they fall off in one to two years. The possibility of crown fires may increase during that red needle period, but it makes sense that fewer fine fuels in the canopy would reduce the fire intensity and make it less prone to transition from a ground fire to a crown fire. Both types of attacks eventually produce more course fuel on the forest floor as the branches break off and the trees eventually fall over.

Research conducted by Daniel G. Gavin, Aquila Flower, Greg M. Cohn, Russell A. Parsons, and Emily K. Heyerdahl found evidence of a “fire proofing effect” for outbreaks of WSB. It does not address the MPB.

Below is an excerpt from their work:

“Extrapolating Results: Reduced Tree Mortality

“Taken together, the tree-ring and modeling studies suggest a lack of synergism between WSB outbreaks and wildland fires. However, a different kind of synergism may exist: Defoliation might dampen the severity of a subsequent wildfire. To explore this possibility, we used existing empirical equations that show the probability of mortality due to defoliation (fig. 3A) and the probability of mortality due to crown scorch (fig. 3B), combined with the simulated results of canopy consumption at different levels of defoliation (fig. 3C), to extrapolate the summed probability of mortality under a range of surface fire intensities and defoliation levels (fig. 3D). The results suggested a distinct “fireproofing” effect of defoliation: The increased risk of mortality by WSB is more than compensated for by reduced foliage consumption during moderate surface fire intensities. For example, trees with 50-percent defoliation have a distinctly lower probability of mortality when surface fires are less than about 74 kilowatts per square foot (800 kW/m2 ).

“However, we considered only the partial effect of defoliation on fire occurrence; we did not take into account other effects of WSB outbreaks, such as mortality of small trees. Of course, field observations are required to test our prediction. Remotely sensed burn severity maps, in combination with prior surveys of insect effects, could address this issue. One such study of the 2003 B&B Complex Fire in Oregon showed that prior defoliation had a marginal effect on reducing fire severity that was not statistically significant (Crickmore 2011). However, an analysis by Meigs and others (2016) of all post-WSB fires in Washington and Oregon from 1987 to 2011 showed that there is a statistically significant reduction in fire severity that persists for up to 20 years following an outbreak. Thus, the effect of defoliation on crown fire behavior modeled by Cohn and others (2014) appears to be confirmed by the analysis of burn severity data by Meigs and others (2016).

“Fireproofing Effect?

“It may seem reasonable to assume that extensive defoliation, causing sustained low levels of tree mortality in mature trees, should have a measurable effect on wildfire occurrence. However, fire is a highly variable disturbance in itself, and it is highly sensitive to specific climate and winds during the fire event. The scale of fuel changes wrought by WSB may be too small to affect subsequent fire probability in ecosystems where fire is limited by fuel moisture and ignition sources rather than fuel availability. Our data show that these two disturbance types do not share similar histories, despite a common link to drought events.

“Nevertheless, we hypothesize a “fireproofing” effect on host trees from defoliation due to WSB outbreaks. Although such an effect has been detected statistically from recent fire events (Preisler and others 2010; Meigs and others 2016), the inferred processes at play remain to be studied in detail at the site scale.”

UPDATE January 5, 2018: These researchers are not the only ones with similar findings on this subject. If you would like to read more, scroll through the articles on Wildfire Today tagged “beetles”.