The report released Friday about the burnover of three firefighters on the Bridger Foothills Fire is jaw-dropping — and not only because there were three firefighters with only two fire shelters to protect them as the flames swept over. It is a well written and thorough report but lists few lessons to be learned, leaving it up to us to read between the lines.

The incident occurred about three miles northeast of Bozeman, Montana on September 5, 2020 when there were 115 active large wildfires burning in the United States which at that time had consumed 3,000,000 acres. Over 22,550 wildland firefighters and forestry technicians were committed across the nation. The August Complex of fires in Northern California had burned 305,000 acres which would be less than one third of its total size when it finally slowed down in the Fall after blackening over one million acres. In August and September there was a serious shortage of personnel to staff the fires. Few if any areas had an adequate number of firefighting resources to initial attack new fires or contain those that had been growing for weeks.

The initial attack on the Bridger Foothills Fire on September 4 included four smokejumpers, “several engines,” plus helicopters and air tankers. According to statistics on the national Situation Report at the end of the day on September 5, the second day of the fire, there were a total of 99 personnel on the fire. Five structures had been confirmed as destroyed and it was on its way to ultimately burning 28 homes and growing to 8,224 acres.

The 37-page report can’t be fairly summarized in a few paragraphs here. I suggest you check it out yourself, then leave a comment below with your impressions.

But briefly, three members of a Montana state helitack crew attacked the fire on September 4, spent the night on the fire, then during the afternoon of the next day were overrun by the fire in the meadow that served as their helispot. They attempted to set an “escape fire”, as used on the Mann Gulch Fire in 1949, to burn off the grass and sage before the fire reached them, but the grass was too green to easily ignite. As the fire approached them two men deployed their aluminized and insulated fire shelters designed to reflect radiant heat, but the third had failed to replace the shelter in his pack he had removed days earlier to lighten his load while on physical training hikes. Two of the men, both large individuals, crammed into one shelter that was made to accommodate one person. The three of them only suffered fairly minor injuries and walked away to a point where they could be transported to a hospital.

From the report:

The firefighters involved in this deployment came to decisions that made sense to them at the time. To learn from this unintended outcome, it is important that you read this without the assumption that this could never happen to you. Instead, please consider that you read this with the luxury of hindsight bias. Our intent is that you find the lessons that you can apply to your program to hopefully avoid experiencing what these folks went through.

Looking back with 20/20 hindsight, there were many things that contributed to the entrapment. If only one of them had occurred, the three helitack crewmen probably would not have been burned over. But the cumulative effect of numerous issues led to this near-fatal event.

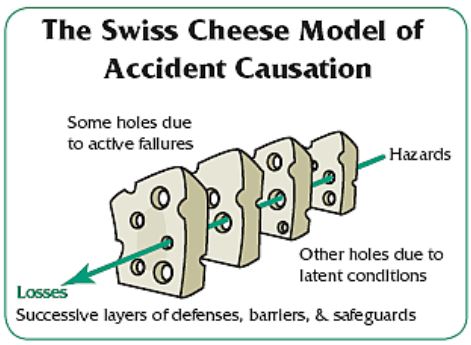

Firefighters are familiar with the Swiss Cheese Model of Accident Causation.

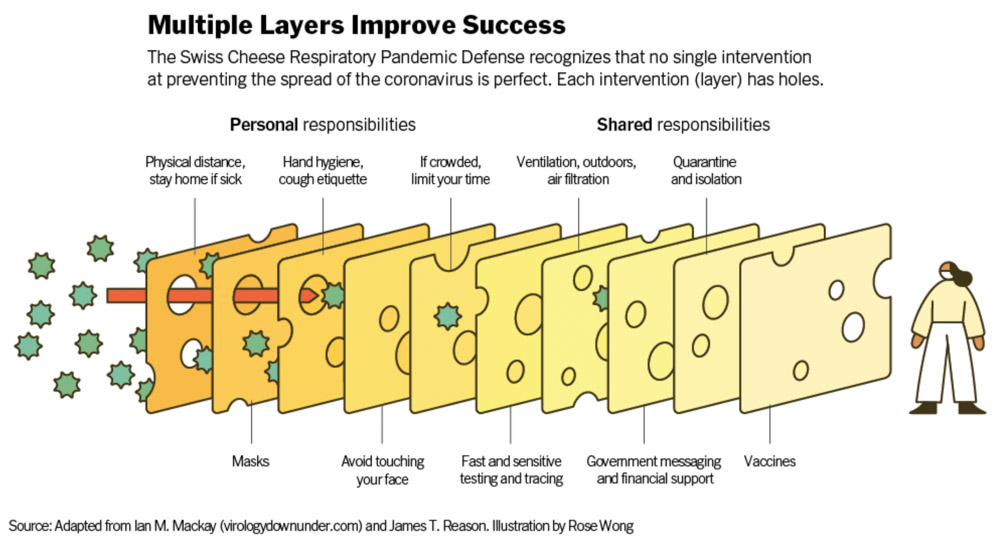

The New York Times published on December 5 a version of the model adapted for the current pandemic:

Many of our readers could study the report and substitute events that happened on the Bridger Foothills Fire for the layers in the Swiss Cheese Model.

Let us know in a comment below what you’re thinking. I’ll get it started with a few:

- Very few firefighting resources initially attacked the fire.

- Communication issues were mentioned many times in the report. Almost every very serious incident within an incident has communication problems.

- Air tankers dropped retardant on the west side of the fire but not the east side that day. A person who was on the fire told Wildfire Today that if retardant had been applied to secure the east side it may have prevented the blowup. With the national fire situation at the time, air tankers may not have been available to continue dropping retardant that afternoon. (Would it have made a difference if the air tanker base 73 air miles away at West Yellowstone had not recently been closed and converted to a call when needed base?)

- At times there was confusion about the location of the three entrapped firefighters. If a safety officer or Division Supervisor had known the exact location of the firefighters and the real time location of the fire, it may have made a difference — there might have been enough time to extract them by helicopter before the smoke and the flaming front made it impossible. THIS RECURRING ISSUE COULD BE SOLVED WITH OFF THE SHELF LOCATION TRACKING SYSTEMS for personnel and the fire! Federal and state wildfire organizations need to make this an urgent priority! This is a life-safety issue and the tools should have been deployed years ago by the federal and state agencies. Funding is not an acceptable excuse. Neither is apathy. Dig deep to find the motivation and the money.

Below is the section of the report that describes the deployment itself, but does not include what led up to it. The names have been changed.

The Deployment

“What do you mean you don’t have your shelter?”

Charlie frantically worked to light off the sage with his fusee. Hands shaking, the sage was lighting better than the grass had before. But it didn’t matter – there was no more time to burn – the fire was coming up fast on him and his crew from both the south and the east.

Charlie turned around to his crewmembers and noticed that one of them, Sam, was already in his shelter. The spot fire that had cut-off their last possible escape route was now well established on the slope below them, and the trees were crowning out with flame lengths of over 100 feet. The wind was blowing so hard that his helmet went flying off his head. Next thing Charlie realized, he was back at the small oval that they had cleared of ground fuels, looking down on his other crewmember Casey, who was laying in the fetal position with his chaps slung over his back and gear bags piled up around him.

“Get in your f**king shelter!” Charlie screamed to Casey.

“I don’t have it – share with me!” Casey shouted back.

“What do you mean you don’t have your shelter?! Did it blow away?!”

It hadn’t blown away, although that would have been easy in the “hurricane-like” winds that were whipping across the hillside in all directions. Casey had taken it out of his pack a few weeks earlier for PT hikes, and never put it back in.

But ultimately, why the shelter wasn’t on the hill did not matter. At this moment, Charlie realized how dire of a situation they were in. Casey was roughly 6’2” and weighed in at around 225 lbs, and Charlie was around 6’ and 190 lbs. And if they were both going to survive this flame front, they would have to squeeze into his one shelter as best as they could.

They could both feel the heat now, and the fire was “cooking.” Charlie ripped out his shelter and struggled to open it. Unlike Sam’s shelter, which Sam later described as “shaking out just like a practice shelter, [or] better,” opening Charlie’s shelter felt like trying to open a ball of tin foil. With Charlie and Casey each pulling at it, they fought to get it open, and valuable moments were lost as they furiously tried to shake it out. The moment they opened the shelter, Casey and Charlie locked eyes, then glanced up at the flames towering above them before they dropped to the ground. The updraft winds at that point were so strong, they had to fight to reach the dirt.

The last-minute nature of their deployment meant that neither Casey nor Charlie were completely in the shelter. Casey had dropped to get his head facing to the north and lined up with the hole he had dug and filled with water, with his legs largely sticking out of the shelter. Charlie was facing nearly the opposite direction, in a crouching position. In this arrangement, neither firefighter could get a seal on the shelter, and embers were blowing in just as fast as Charlie could sweep them out. Casey screamed over the radio that they had deployed, a transmission that was copied by air attack. Charlie then took the radio and remembers transmitting that there were three of them who had deployed, with only two shelters. Air attack, who confirmed that three people had deployed, did not recall hearing that there were only two shelters.

Charlie later described how, in their initial arrangement, “I couldn’t take it anymore, I couldn’t get air, and it felt like I was in a microwave.” In this moment of desperation, Charlie stood up, thinking nothing could be worse than being crammed into the shelter, in the heat, without any way to breathe. Charlie immediately realized how much worse it could get with the fire burning all around and was forced to dive back into the shelter. This time, Charlie was shoulder to shoulder with Casey, which allowed them to get a slightly better seal.

The experience, however, was still far from comfortable. Unable to breathe and battling through the extreme heat, Charlie “was certain we were gonna die. [I thought] every second was our last second.” Casey described the sensation of trying to breathe as like “if anyone has ever been cleaning around you and it’s extremely potent – it’s like that but it’s on fire.” To try to alleviate the heat, he began splashing plastic water bottles on himself and Charlie, squeezing 4-5 bottles out along their backs.

Sam was equally certain that they were not going to survive. “100%, I thought we were dead. No doubt … I couldn’t breathe.” To try to get a breath, he wet down his shirt and started digging a hole into the ground. Although opening the shelter had been easy, Sam struggled in the wind to create a strong seal. For the fifteen or so minutes that Sam remained in the shelter, he was absolutely terrified for his life.

Casey and Charlie emerged from their shared shelter around 8 minutes after they first got in, after the initial flame front had passed. Their surroundings, however, still resembled a hellscape. Casey’s line gear, which he had been unable to throw very far away from the deployment site, was on fire and burning Charlie’s leg, so Charlie kicked it farther away. Outside of the circle, the cans of bug spray and sunscreen in the bag exploded. Combined with the combustion from the remaining fusees, the explosions caused the gear to burn down to nothing.

Even without the flames, the heat, smoke, and winds were still so intense that Charlie and Casey reentered the shelter, where they remained for another eight or so minutes, getting continuously hammered by the wind. Eventually, while getting oxygen was still nearly impossible, it became clear that they were going to be miserable whether they were in the shelter or out. Knowing that everything was nuked around them, and the worst of the heat had passed, they emerged from the shelter again. But the beating afflicted by the fire was still far from over.

Sam’s experience: “I deployed my shelter and within probably a minute or two could hear, feel, and see the fire going over and around us. The inside of my shelter glowed red … there was no place to get a cool clean breath. Embers blew inside my shelter and I would push them out. I tried to dig in the ground to get a clean breath and was unsuccessful. At some point I remember Charlie asking how I was doing. I responded with ‘Not good man, I can’t f**king breathe.’ I thought about my wife and kids and knew with some certainty that I was dead.”