The more knowledge firefighters have about the fluid dynamics of wildfires the better equipped they will be to take on the tasks of igniting prescribed fires and suppressing wildfires.

Below is an article written by Rod Linn, who leads development, implementation, testing, and application of computational models of wildfire behavior in the Earth and environmental sciences division at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico. From Physics Today 72, 11, 70 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.4350

Fluid dynamics of wildfires

Wildland fires are an unavoidable and essential feature of the natural environment. They’re also increasingly dangerous as communities continue to spread away from urban areas. Unfortunately, a century of wildfire exclusion—the strategy of putting out fires as fast as they start—has led to a significant buildup of fuel in the form of overgrown forests. Continuing to keep wildfires at bay is simply not sustainable. In 2018, nearly 60,000 fires scorched parts of the continental US. California wildfires exemplify what can happen when they burn through communities: In November alone that year fires killed more than 90 people and destroyed some 14,000 homes and businesses.

Decision makers are striving to find ways to manage the consequences of those fires and yet still allow them to thin out dense, fuel-heavy forests and reset ecosystems. Among other things, the goal requires that land managers be able to predict the behavior of wildland fires and their sensitivity to ever-changing conditions. Many factors, including the interactions between fire, surrounding winds, vegetation, and terrain, complicate those predictions.

That ambient winds influence fire behavior is well known. Less understood is how fire influences the winds and how the feedback affects the fire’s evolution. As the fire rages, it releases energy and heats the air. The rising air draws in air below it to fill the gap in much the same way as air is drawn into a fireplace and rises up a chimney. The interaction between rising air and ambient winds controls the rate at which surrounding vegetation heats up and whether it ignites. The interaction thus determines how quickly a fire spreads.

FUEL MATTERS

The influence of the fire–atmosphere coupling is much greater in wildland fires than in building fires. Wildland fires are fed by fine fuels—typically grasses, needles, leaves, and twigs; often, tree trunks and large branches do not even burn. Buildings burn thicker fuels, such as boards, furniture, and stacks of books. The difference matters because fine fuels exchange energy more efficiently with surrounding hot air and gases. In those hot, fast-moving gases, the fuels’ temperature rises quickly to the point where they ignite.

But the converse is also true. Because wildland fuels are primarily fine, they are also efficiently cooled when the surrounding ambient air is cooler than they are. That means that the indraft of air caused by a fire may actually impede its spread. A rising plume can draw cool air over foliage and litter near a fire line and prevent those fine fuels from heating. The grasses just outside a campfire ring are a case in point: They are continuously exposed to the fire’s radiant heat, but the cool indraft effectively prevents them from reaching the point of ignition.

The spread of a wildfire is sometimes conceptualized as an advancing wall of flame that the wind forces to lean toward unburned fuels that then ignite in front of the fire. Although that wall-of-flame paradigm simplifies models of fire behavior, it is not correct. Convective cooling would prevent the wall of flame from spreading by radiation alone, and for convective heating to spread the fire, the wind would have to be strong enough to lean the flame to the point where it touches the unburned fuel. Were that true, the fires would be unable to spread in low-wind conditions because the buoyancy-driven updrafts would keep the flames too upright.

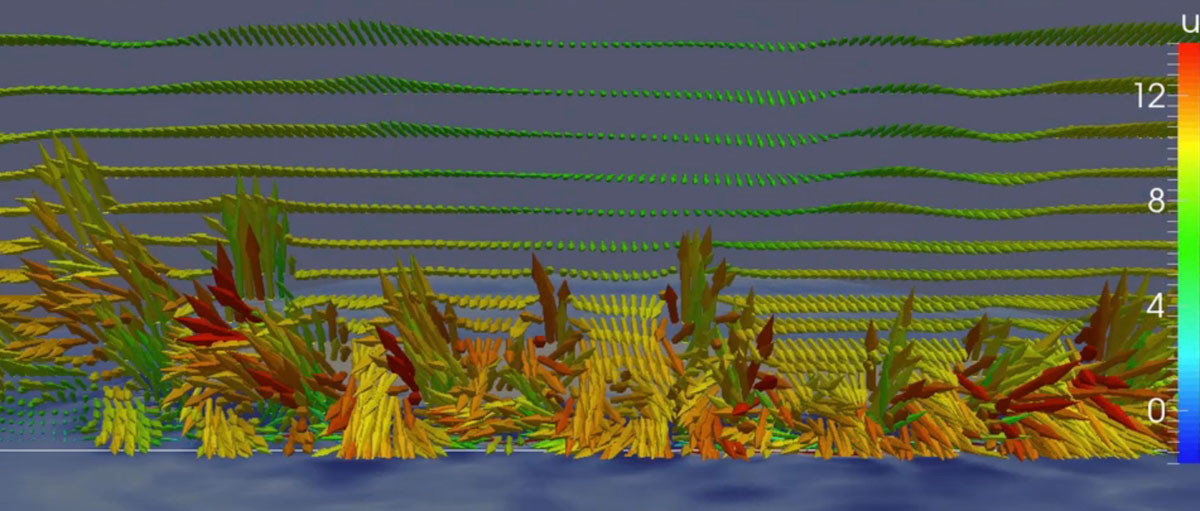

If you were to look upon an advancing wildfire from the front, you would actually see a series of strong updrafts, visible as towers of flame that are separated by gaps, as shown in figures 1 and 2. The towers are regions where the buoyancy-driven updrafts carry heat upward. They are fed by ambient wind drawn into the gaps between them, as described earlier. When the ambient wind is strong enough, it pushes air through the gaps between the towers, but that air is heated as it blows over burning vegetation. The motion of hot gases through the fire line disrupts the indraft of cool ambient air and ignites grasses and foliage in front of the fire. That’s the primary way a wildfire spreads.

A second factor that influences the spread is the shape of the fire line, because different parts of the blaze compete for wind. The headfire, the portion moving the fastest, often has trailing flanking fires that form a horseshoe shape and open up to the ambient wind. Part of that wind gets redirected toward the flanks of the horseshoe. The strength, length, and proximity of the flanking fires to each other thus help determine how much wind reaches the headfire. The narrower the horseshoe is, the larger the fraction of wind diverted to the flanks, the lower the wind speed reaching the headfire, and the slower it spreads.

Another factor to be considered is the spatial arrangements of fuels. The potential for wildfires spreading from the crown of one tree to another is reduced when the spacing between trees increases. In that case more horizontal wind is required for flames to jump between trees. Indeed, removing trees is a common fire-risk-management practice. But the strategy behind it is more complex than just removing fuel. Gaps in a forest canopy also make it easier for high-speed winds above the canopy to reach fires on the ground. So although reducing the number of trees might reduce the crown-to-crown fire activity, it might increase the spread rate of a surface fire.

PRESCRIBED FIRE

In some regions of the US, land managers counter the threat of wildfires and promote ecosystem sustainability by purposefully lighting fires. Carefully controlled, prescribed burns, which clear duff and deadwood on the forest floor, are often lit at multiple locations; fire-induced indrafts at one location influence fires at other locations. For example, a single line of fire under moderate winds might reach spread rates and intensities that are undesirable or uncontrollable, but the addition of another line of fire upwind can influence how much ambient wind reaches the original fire and thus reduces its intensity.

The spread of the upstream fire line, ignited second, is purposefully limited, as it converges on the area downwind where the first fire has burned off fuel. Practitioners can manipulate the flow of wind between fire lines by adjusting the spacing between ignitions. Fire managers might tie the various ignition lines together—reducing the fresh-air ventilation, increasing the interaction between the lines, and causing fire lines to rapidly pull together—to give themselves more control over the spread.

The interaction between multiple fire lines can even stop a wildfire in its tracks. When firefighters place a new fire line downwind of a fire, they often hope that the indrafts will pull the so-called “counter fire” toward the wildfire and remove fuel in front of it. Unfortunately, the maneuver requires a good understanding of the wildfire’s indraft strength. Too weak an indraft could turn the counter fire into a second wildfire.

After realizing the huge significance of the wind interactions in wildfires over the past two decades, the science community is striving to better account for them. Those efforts should improve predictions of how a wildfire will behave in various conditions. To that end, some researchers, including me, use computer models to explicitly account for the motion of the atmosphere, wildfire processes, and the two-way feedbacks between them. Others perform experiments at scales ranging from meters (such as in wind tunnels) to kilometers (such as in high-intensity fires on rugged topography) for new insight on the nature of those fire–atmosphere interactions or to confirm existing models.

SIMULATION VIDEO

(If you’re having trouble playing the video, you can see it on YouTube)

The [above] simulation illustrates the dynamics of wind fields in a vertical plane, located at the white horizontal line, as a wildfire approaches it. The colors mark the speed u of the wind perpendicular to the plane, with red indicating motion toward the viewer (out of the screen), and blue indicating motion away from the viewer. As the clip shows, the fire starts to influence the winds long before it reaches the plane, and the wind patterns change in scale and character as the fire approaches. As the fire crosses the plane, the towers and trough flow patterns become apparent. Some locations show strong upward motion, whereas others have strong horizontal or even slightly downward motion. The colors on the ground surface illustrate the convective cooling (blue) that occurs as a result of the movement of cool air over the fuel— grasses in this simulation—and locations in front of the fire where the fuels are being convectively heated (red).