Today we have the ninth article of our series in which we ask current and retired leaders in the wildland fire service to answer 12 questions.

We appreciate everyone who is cooperating with this project. Some of their responses may add to the knowledge base of our new firefighters coming up through the ranks. If you would like to nominate someone who would be a good candidate for these questions, drop us a line through our Contact Us page. And their contact information would be appreciated.

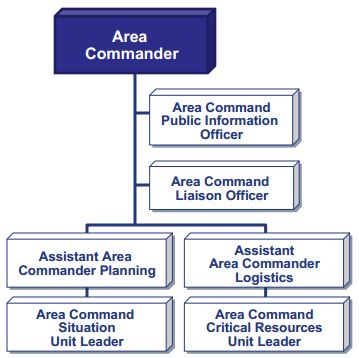

Below we hear from Edy Rhodes, a former Area Commander. She worked for the U. S. Forest Service for 25 years before transferring to the National Park Service, retiring as their Division Chief of Fire, Aviation and Structural Fire.

****

When you think of an excellent leader in the fire service, who comes to mind first?

Too many to mention, but here are a few:

- Steve Pedigo, Dick Cox, Rex Mann, and Bobby Kitchens who promoted incident management teams in the South resulting in involvement in the national Type 1 rotation.

- Rick Gale and Mike Edrington, in their roles Fire Directors, as Area Commanders and as leaders of the 520/620 Steering Committee and cadre. They mentored countless individuals in their careers over the years.

- Also, the Forestry Technicians who taught me the basics and kept me safe while giving me room to make mistakes during my early career years. Junior Gay, Daniel Boone NF and Bruce Harvey, NF’s in FL, come to mind!

What is one piece of advice you would give to someone before their first assignment as an Incident Commander?

In general, “Before you get on the horse, be ready to ride!” Specific to large incident management, provide strategic leadership and all it entails from being proactive, confident, decisive and a good communicator with your team and all stakeholders involved.

If someone is planning a prescribed fire, what is one thing that you hope they will pay particular attention to?

An approved plan, appropriate weather conditions, adequate resources, and good communication by all.

One of the more common errors in judgment you have seen on fires?

Assuming that everyone is on the same page; Failing to “connect the dots” and “close the loop” with those that need critical information that may affect them.

One thing that you know now that you wish you had known early in your career?

What a rewarding career that fire management would be! The opportunities to travel, see remarkable places, and work with extraordinary people has enriched my life tremendously.

The stupidest mistake you have seen on a fire?

It was on a RX burn, when the fire jumped the line on our section, setting off a huge, grassy field next to the municipal sewage treatment plant, which was adjacent to the regional airport. Thank goodness, we were able to get the treatment plant personnel to turn on the effluent sprinklers, which extinguished the fire, before the smoke completely shut down airport operations. We got a lot of phone calls on that one!

Your most memorable fire?

The Yellowstone Fires of 1988.

The funniest thing you have seen on a fire?

A couple of mules got loose from their pack string and went bucking down the mountain scattering their load everywhere!

The first very large fire you were on?

The Hog Fire, Klamath NF, 1977.

Your favorite book about fire or firefighting?

Young Men and Fire

The first job you had within the fire service?

Forester Trainee and firefighter on a local crew on the Daniel Boone National Forest, KY.

What gadgets, electronic or otherwise, can’t you live without?

Laptop, iPhone and iPad. Love my Google maps!