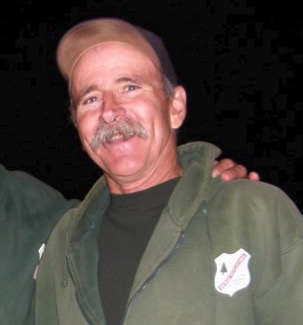

On Sunday November 5 we lost another wildland firefighter to the suicide epidemic. After completing his shift that morning at CAL FIRE’s Station 20 in El Cajon, California Captain Ryan Mitchell took his own life at the Interstate 8 Pine Valley bridge in San Diego County near Pine Valley.

“This tragic and unexplainable incident has affected many personnel in the Unit, both those that knew Ryan and those that responded to the incident”, Unit and County Fire Chief Tony Mecham wrote Sunday in a message to the county firefighters. “I am proud of our personnel and the efforts undertaken today under very difficult conditions. I especially want to thank those personnel who spent the day at the scene and accompanied Ryan to the Medical Examiners Office this evening.”

“While we may never know exactly what lead to this tragic event”, Chief Mecham continued, “what we do know is that mental health issues are real and no one should feel embarrassed or ashamed to ask for help. Circumstances at work and in our personal lives affect our mental health and quality of life. There are many resources available to all of us through Employee Support Services, Employee Assistance Programs and our own personal network.”

On November 4 we wrote about the shocking number of wildland firefighters who have taken their own lives. According to Nelda St. Clair of the Bureau of Land Management we lost 52 in a two-year period, 2015 to 2016.

Chief Mecham is right. Help is available.

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255. Online Chat.

- Wallet card that lists the signs of suicide risk.

- Anonymous assistance from the Wildland Firefighter Foundation: 208-336-2996.

- National Wildland Fire and Aviation Critical Incident Stress Management Website.

- Code Green Campaign, a first responder oriented mental health advocacy organization.

- Eric Marsh Foundation for Wildland Firefighters

- Would you rather communicate with a counselor by text? If you are feeling really depressed or suicidal, a crisis counselor will TEXT with you. The Crisis Text Line runs a free service. Just text: 741-741

The image below that we posted on Facebook is an abbreviated version of help sources that could be posted on bulletin boards or stuffed into employee mailboxes.