Via Chief John Hawkins (@Jhawkfire)

Tag: California

The Air Force has one firefighting dozer team

The only firefighting dozer team in the U.S. Air Force is at Vandenberg Air Force Base in southern California. The 30th Civil Engineer Squadron heavy equipment operators’ fire dozer team consists of approximately ten Airmen and civilian workers. Their job is to support the firefighters by helping to limit damage and contain the spread of wildfires.

“Because of the sheer size of our equipment we can accomplish a lot within seconds,” said Staff Sgt. Mark Robertson, a heavy equipment operator. “When we go out to a fire, those who have already responded breathe a sigh of relief because we can accomplish a huge amount of work in a short amount of time.”

When a fire breaks out, the base firefighters are the first to respond. When the fire is too difficult to control, the fire dozer team is called to assist.

“We are supporting the fire department, and will get their call if they need us,” said Raymond Boothe, 30th CES equipment supervisor. “We are not sitting around waiting for a call though — we are constantly working all over base, performing our job as heavy equipment operators.”

“Vandenberg is the only base in the Air Force that has a fire dozer team,” said Robertson. “So this is the only place in our career that we are going to get this kind of experience and training.”

Airmen also receive a Red Card certification, which states the holder has the experience and training necessary to fight wildfires. This certification is utilized by both state and federal fire agencies and is useful for civilian jobs across the nation.

Another significant component of the job is supporting the space mission. The fire dozer team is on stand-by during every launch, prepared to contain fires that start and prevent damage to base assets.

San Diego power company wants customers to pay 90% of wildfire costs

San Diego Gas and Electric wants to raise the rates their customers pay in order to cover the costs the utility incurred after the failure of their power lines caused the Witch Creek, Guejito, and Rice Canyon fires in 2007. The fires destroyed more than 1,300 homes in southern California, killed two people, and caused massive evacuations. The Witch Creek Fire which started near Santa Ysabel burned 197,990 acres.

SDG&E still owes $421 million resulting from legal settlements that were not covered by their insurance. The San Diego Union-Tribune reported that on Friday the company asked for permission to have their customers pay 90 percent, or $379 million, of the remaining costs from the fires. The stockholders would pay $42 million.

In the years since the 2007 fires caused by SDG&E’s powerlines, the company has replaced a small percentage of wooden poles with steel poles, stepped up tree trimming programs near power lines, installed over 100 weather monitoring stations, staged private firefighters in areas with extreme fire danger, made a Type 1 helicopter available to firefighters for two years, and initiated a program to proactively shut off power to areas if they feel wind and weather conditions could cause their lines to fail and ignite fires.

The program of turning off power to prevent fires, has been controversial.

From the Times of San Diego in 2014:

San Diego County Supervisor Dianne Jacob, a fierce critic of SDG&E who represents East County communities, asked the utility to shut off electricity only as a last resort.

“I’m deeply concerned about any shutoffs because they pose risks to property and life in an emergency, especially in areas where firefighters need access to well water,” Jacob said. “I urge the utility to cut power only as a last resort and only if there’s an actual system failure that could ignite a wildfire.”

The Laguna Fire, 45 years ago today

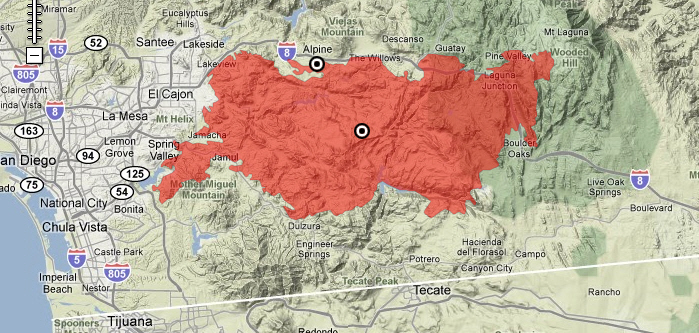

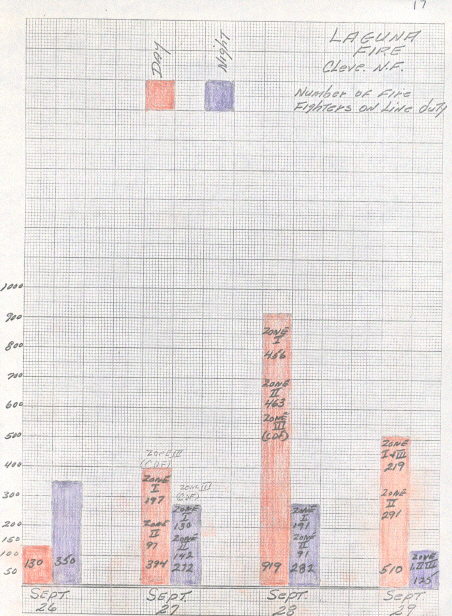

At 6:15 a.m. PT on September 26, 1970 the Laguna Fire started on Mt. Laguna east of San Diego near the intersection of Kitchen Creek Road and the Sunrise Highway. By the time it was stopped on Oct. 3 1970 it had burned 175,425 acres, killed eight civilians, and destroyed 382 homes. In the first 24 hours the fire burned 30 miles, from Mount Laguna, California into the outskirts of El Cajon and Spring Valley, devastating the communities of Harbison Canyon and Crest. Previously known as the Kitchen Creek Fire and the Boulder Oaks Fire, it was, at its time, the second largest fire in the history of California.

The Laguna fire started from downed power lines during a Santa Ana wind event. Santa Anas are warm, dry winds that characteristically appear in Southern California during autumn and early winter. They can be typically caused by a pressure differential between a high in the Great Basin and a low in the eastern sub-tropical Pacific.

Richard Raybould, Fire Control Officer on the Descanso District of the Cleveland National Forest, was the first Fire Boss on the fire. Shortly after it started he was told by the Cleveland National Forest dispatcher that due to other large fires burning in southern California at the time, there were no organized crews available. The 40 to 60 mph winds made the use of firefighting aircraft impossible.

By noon the day it started the fire was divided into three Zones, each with a Fire Boss. Zone Fire Bosses included at various times, Richard Raybould, Howard Evans, Lynn Biddison, and Baldwin (unknown first name). The Zones were overseen by a General Headquarters, or GHQ, headed by Myron Lee, the Forest Fire Control Officer for the Cleveland National Forest.

The Laguna Fire and the others that occurred in southern California in September of 1970 led to the development of the Incident Command System (ICS) which morphed into the National Incident Management System (NIMS).

The day the Laguna fire started I was a crewmember on the El Cariso Hot Shots, and we were mopping up a brush fire near Corona a couple of hours north of the Laguna Fire.. We heard the radio traffic that morning about the new fire and the reports that it was cranking. It was The Big One. And there we were, stuck doing the dreaded mopup on a fire that was pretty much out. For hours we kept poking around trying to find something hot to put out, as we kept hearing more about the fire on Laguna Mountain that was hauling ass. We wanted to be there.

Finally, late in the afternoon we were dispatched to it. By the time we got to Pine Valley it was after sunset, and for some reason, I, a first-year hot shot, was in the pickup with Ron Campbell, the Superintendent. The two open-top crew carriers were behind us. As we drove into Pine Valley the hills adjacent to the community to the south and east were alive with the orange flames of the fire. The one radio channel we had on the Cleveland National Forest was completely jam-packed with radio traffic. You could not get a word in edgewise. We knew that this was going to be one that we would remember.

We worked on the fire all that night and then pulled several more shifts before we were transferred to the Boulder 2 fire in Cuyamaca State Park, which was a rekindle from the Boulder fire.

The video below Countdown to Calamity, documents the fire siege in southern California that occurred in late September, 1970, including “the fire destined to dwarf all the others”, the Laguna Fire.

Remains found of a fourth person killed in the Valley Fire

The Trinity Alps pack string on the River Complex of fires in California

In this video, packer Erik Cordtzon of the Shasta-Trinity National Forest in northern California talks about using the Trinity Alps pack string of mules and horses, one of three pack strings on the forest, to haul cargo in and out of the River Complex of fires.

We appreciate seeing videos like this of firefighters simply talking about their job. It can give the public a better understanding of what they do and what they go through on a daily basis. It’s very easy to do this. One of the keys, however, is to have good audio. An external microphone, as used in this video, is essential — they are even available for smart phones.

If the video is uploaded to YouTube they can be seen by a much, much wider audience than if they are hidden on Drive. And Facebook videos can’t be easily embedded onto other sites.