In case you came to our website yesterday and saw the green banner saying the site was closed for the day to recognize the global #ClimateStrike, we are back in service as you can see.

On Friday millions of people across the world, many of them young, assembled to help bring awareness to what I and others are convinced is an emergency — a climate emergency. The more scientists learn about the changing climate the more serious the situation looks. A few years ago we were hearing that we had to reach net zero carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 2050. That is a long way off and many of us will not be around then. But the young people marching today will be stuck with the results of what we do between now and then.

The preliminary numbers say there are at least 3 million people in today’s #ClimateStrike And that is before counting North and South America!! To be updated… #FridaysForFuture pic.twitter.com/9C8SE5kSxZ

— Greta Thunberg (@GretaThunberg) September 20, 2019

We still need to reach net zero CO2 emissions by 2050, but we can’t wait until 2049 to begin making changes. Scientists are saying that to reach that goal, emissions would have to start dropping well before 2030 and be on a path to fall by about 45 percent by 2030. The longer we wait to begin making significant changes, the more difficult it will be to meet the 2050 goal.

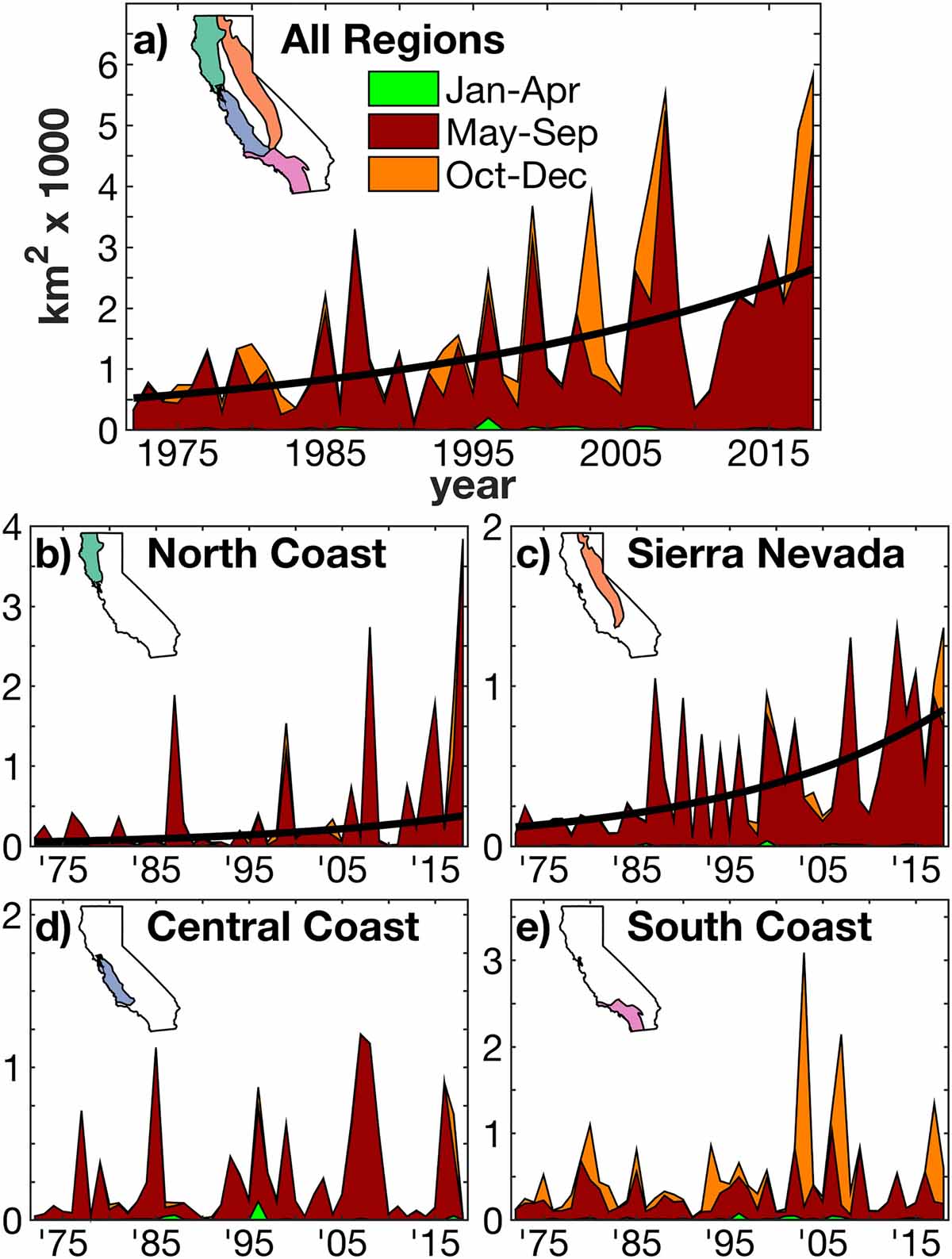

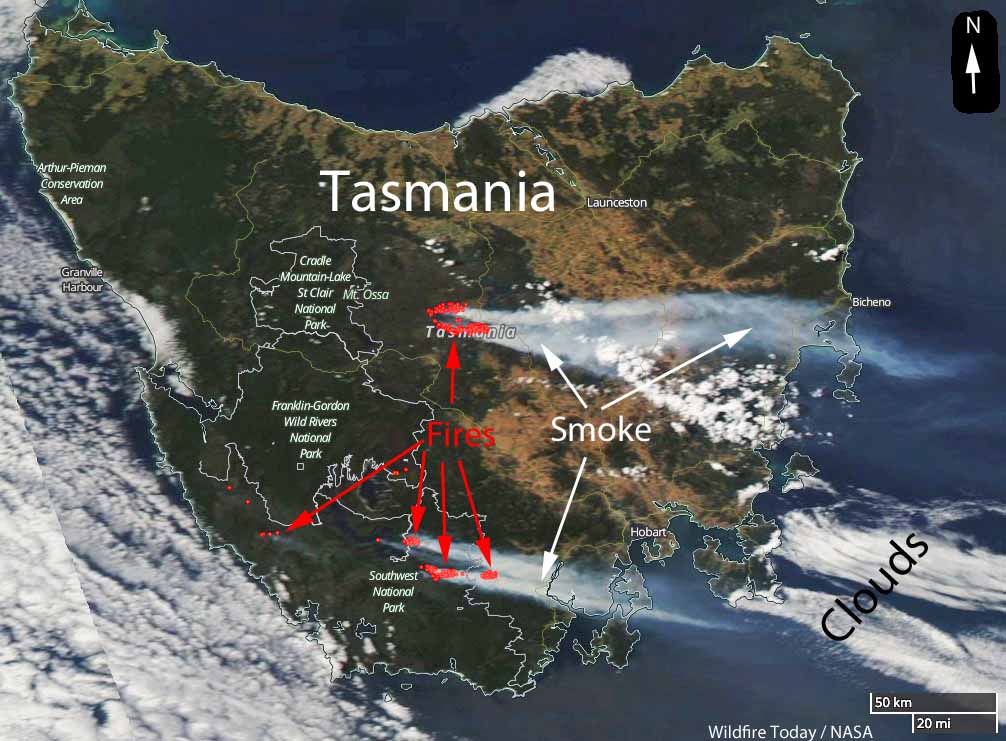

Scientists estimate that wildland fires make up 5 to 10 percent of annual global CO2 emissions when taking into account renewed forest growth in the burned areas. Fires also release other greenhouse gasses such as methane. Experts estimate that the wildfires in California’s North Bay in October of 2017 emitted as much CO2 in one week as all of the state’s cars and trucks do in one year.

Up until now fire management in developed countries has virtually received a free pass when it comes to CO2, at least compared to what it could become in the next 10 to 15 years. There is world-wide pressure now to rapidly reduce the burning of fossil fuels. It is only a matter of time before we start hearing a chorus saying all vegetation fires are “bad”, including prescribed or “good fires”, using a term now being used by some U.S. Forest Service personnel.

Land managers should be thinking about how to deal with strong pressure to significantly reduce CO2 emissions from burning vegetation. Part of the answer is additional firefighters, engines, dozers, helicopters, and air tankers. The U.S. Forest Service budget for wildland fire has remained flat for the last several years, while the costs of suppression infrastructure has increased. In light of the climate emergency, allotting fewer real dollars to suppression is counter intuitive. Congress and the President need to take action on this budget issue.

Fuel treatment projects, including mechanical projects and prescribed fires, can reduce the size and resistance to control of wildfires. However, pressure to reduce CO2 emissions could make it more difficult to obtain approvals to conduct prescribed fires even though the results if done on a large enough scale can reduce emissions from wildfires over the long term. But it will be difficult to develop the formula for the right mix and priorities of mechanical treatments, prescribed fires, wildfire suppression, or doing nothing.

There are many irons in that fire, so to speak, such as dealing with smoke, protecting communities, restoring forests, conserving water resources, wildlife, endangered species, and of course the amount of CO2 and other greenhouse gasses coming out of our forests as they burn one way or the other. It remains to be seen if all of those goals can be satisfied as we move closer to the climate emergency tipping point. Some of them may have to be de-emphasized. Land managers might be accused of being selfish if they insist on attempting to accomplish all of these traditional objectives that may exacerbate the climate for the entire planet. As well meaning as de-emphasis might me, unless skillfully implemented using the best science, the unintended consequences could actually increase CO2 emissions over time.