Above: The burned drone. Photo by Cameron Austin-Connolly

(Originally published at 5:10 p.m. PDT July 11, 2018)

A small drone started a vegetation fire when it crashed near Springfield, Oregon this week. On July 10 Cameron Austin-Connolly was flying his drone over a field when a large unleashed dog left its owner, ran and jumped on him. The impact knocked the controller out of his hands and the drone immediately went out of control and crashed. As you can see in the video (that Mr. Austin-Connolly gave us permission to use) within about three seconds the still operating camera recorded flames.

You can also see two dogs running at Mr. Austin-Connolly.

He wrote on his Facebook page:

My drone crashes and when I go to look for it I saw smoke and flames so I called 911. Springfield FD quickly showed up and put out the flames. They even returned my drone and gopro. The Fire Marshall said that was their first drone fire.

In case you’re wondering about the reaction of the dogs’ owner, Mr. Austin-Connolly said he just kept walking and didn’t say anything.

Mr. Austin-Connolly told us, “it is a hand built first person view drone, or FPV done. Some people also call them racing drones since they are fast.”

He said it was using a lithium polymer, or “lipo”, battery.

Most small consumer-sized drones use lithium ion batteries, while racing drones generally operate with lithium polymer batteries.

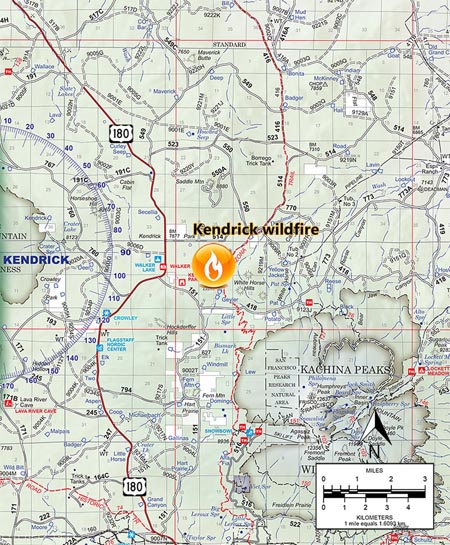

In March we wrote about the crash of a drone that started a 335-acre fire on the Coconino National Forest in Northern Arizona. Few details about that drone were available, except that it was about 16″ x 16″. The comments by our readers developed a great deal of information about rechargeable batteries and the possibility of them catching fire. We also learned about several other drone crashes that started fires.

In May we published an article about the fact that electric vehicles with lithium-ion batteries present a complex and hazardous situation for firefighters responding to a vehicle accident.

The fact is, there are many examples of both lithium ion and lithium polymer batteries catching fire. There is no doubt that when a lithium ion battery is subject to an impact, a short circuit can occur in one or more of the cells, creating heat which may ignite the chemicals inside the battery. This can spread to the adjoining cells and lead to the condition known as “thermal runaway” in which the fire escalates. If as in a vehicle, there are thousands of batteries, it can be extremely difficult to extinguish the blaze. And worse, it can reignite days or weeks later.

When compact fluorescent light bulbs were introduced they saved energy but were slow to get fully bright and many people thought the color of the light was unpleasant. I knew then that it was immature lighting technology. There were going to be better options. Now LED bulbs save even more energy, come in various light temperatures (colors), and illuminate at near full brightness immediately. For now, they are expensive, but will still pay for themselves in three to five years.

Lithium ion and lithium polymer batteries are the compact fluorescent bulbs of battery technology. They are too heavy, don’t hold enough power, and they too often catch fire. No one wants to be on an airplane when flames erupt from an e-cigarette, cell phone, wireless headphones, or laptop computer, all of which can ignite even if they are turned off.

So until that next major step in battery technology occurs, what do we do about drones? Is the risk so low that we should not be concerned? When land managers enact fire restrictions during periods of high wildfire danger, do we also prohibit the use of drones? Should drones ever be allowed over vegetation in a fire-prone environment during wildfire season? And what about the hundreds of drones owned and operated by the Department of the Interior that flew 5,000 missions last year? Not all are battery operated, but some are.

We thank Mr. Austin-Connolly for providing the information, photos, and the video. When we asked, he said, “If my experience can be helpful I’m all for it.”

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Kelly.

Typos or errors, report them HERE.