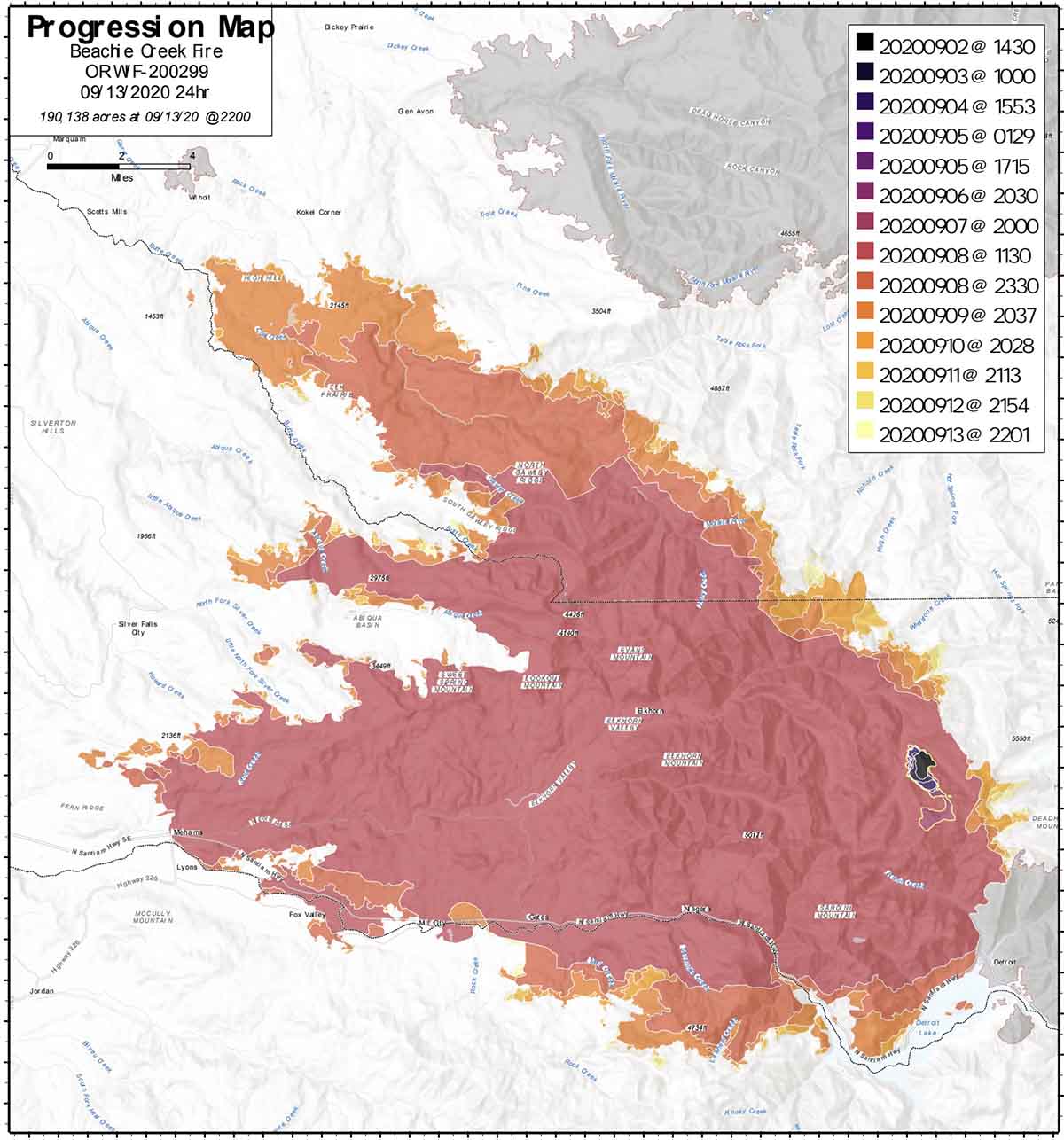

A county in Oregon has filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Forest Service that is related to the Beachie Creek Fire that burned over 193,000 acres east of Salem, Oregon in September.

The Davis Wright Tremain law firm in Portland submitted a request September 28 on behalf of Linn county, requesting records related to the fire. The request cited the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) which requires a federal agency to respond within 20 business days, unless there are “unusual circumstances,” or notify the party of at least the agency’s determination of which of the requested records it will release, which it will withhold.

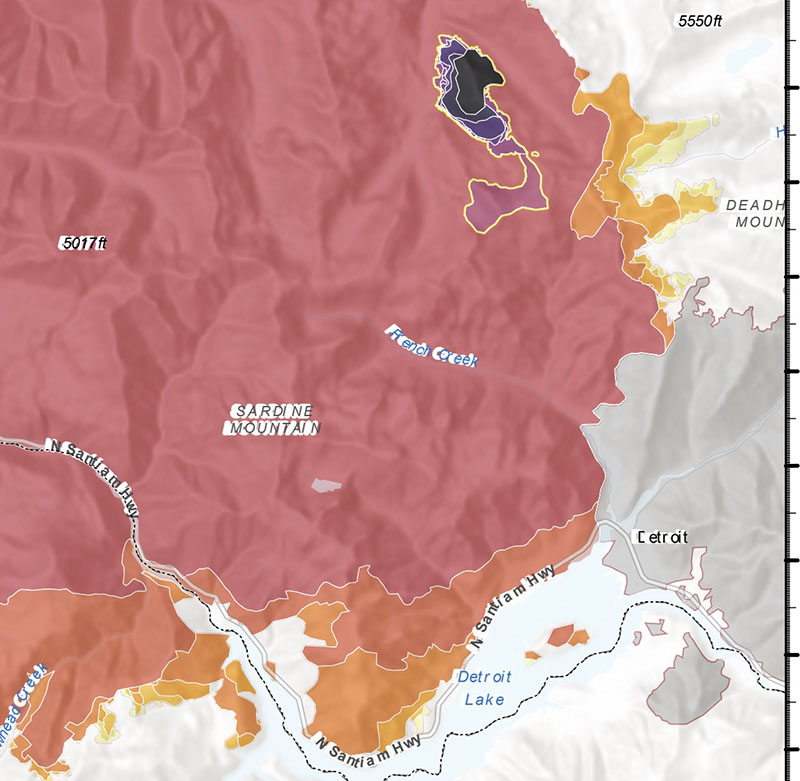

About 12 percent of the Fire was in Linn County, with the rest in Marion and Clackamas Counties. The Linn-Marion county line is near Highway 22 close to the communities of Lyons, Mill City, Gates, Detroit, and Idanha where many structures were destroyed.

The Forest Service replied to the FOIA in a letter dated the next day, saying (and this is an exact quote):

Please be advised your request is not perfected at this time and we will be reaching out to you to discuss clarification once it has been to thoroughly review.

After not receiving the documents or apparently hearing nothing further from the Forest Service, the attorneys for Linn County filed a lawsuit November 2, 2020 in the U.S. District Court in Eugene, Oregon.

Below is an excerpt from the complaint:

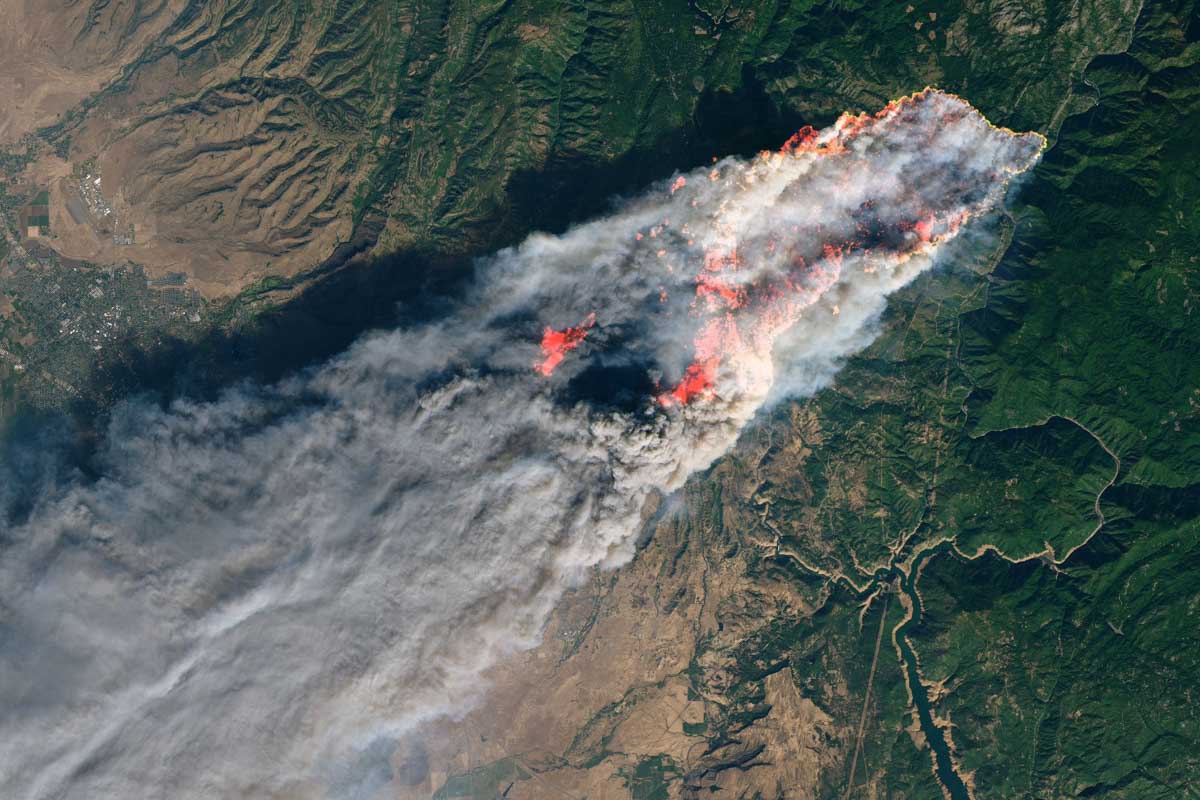

During its first few days, USFS officials attempted to extinguish the fire, which at that point was 10 to 20 acres, but could not effectively utilize traditional means because the fire was burning on the side of a steep, densely forested mountain…The Beachie Creek Fire thus continued to burn at a relatively small size for days but became a conflagration in early September as conditions became windy and dry, jumping to 200 acres on September 1, 2020, then growing to 500 acres after that. When a windstorm that had been predicted for at least one week prior hit Labor Day night, the Beachie Creek Fire exploded, torching ancient rainforests in the Opal Creek area and roaring down North Santiam Canyon. The fire destroyed the communities of Mill City and Gates, decimated thousands of structures and claimed at least five lives.

The fire was reported August 16, 2020 in the Opal Creek Wilderness about six miles northwest of Detroit Lake in Oregon, about 38 miles east of Salem. According to records in the daily national Incident Management Situation Report and GIS data, the fire was:

–10 acres August 26, 10 days after it was reported;

–23 acres August 31, 15 days after it was reported;

–150 acres September 3, 18 days after it was reported;

–469 acres September 7, 22 days after it was reported; (just before the wind event that began that night).

From the Statesman Journal:

Forest Service officials told the Statesman Journal it tried to put out the fire during its first few days, and that fire crews dumped “a ton of water” on it. They said they couldn’t safely get firefighters in to extinguish the blaze on the ground, which at that point was 10 to 20 acres, because it was burning on the side of a steep, densely-forested mountain.

“You have deep duff, significant litter and a ladder fuel,” [Rick Stratton, a wildfire expert and analyst] said. “That’s why it doesn’t matter how much water you put on it, it can hold heat. You have to have people on the ground working right there, in an area that elite firefighters turned down twice.”

Firefighters worried about flaming debris coming down the mountain and being unable to escape. Firefighter safety has been emphasized since 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots were killed in an Arizona wildfire.

A fixed wing mapping flight at 8:37 p.m. PDT September 9 found that in about 48 hours the fire had spread 25 miles to the northwest from its point of origin and had burned at that time 310,549 acres.

Many fires started in Oregon around August 16 from lightning that moved through northern Californian into Oregon. Conventional wisdom is that the Beachie Creek Fire was a result of the this storm, although the Forest Service has not officially disclosed the cause. Complicating the issue is the reports that the gale force winds of September 7 and 8 caused multiple power lines to fail, starting additional fires which eventually burned into the Beachie Creek Fire.

This fire and others in Oregon, California, and Colorado were crying out for limited numbers firefighters, engines, helicopters, and air tankers but the fire suppression infrastructure available fell far short of the need. This meant that after the wind subsided, putting the huge blazes out quickly was not possible — without rain. Stopping a fire pushed by very strong winds is not possible, regardless of the air power or ground-based firefighting resources available.

Much of Oregon was also in severe to extreme drought along with Nevada, Arizona, and Colorado. This resulted in the moisture content of the vegetation (or fuel) being low, making it receptive to igniting and burning more quickly and intensely than if conditions were closer to average.

Well over 1,000 structures burned. Some of the communities that were hardest hit included Detroit, Mill City, Santiam River, and Gates.

The information Linn County requested from the Forest Service was about the agency’s policy for managing fires, and the Beachie Creek Fire in particular. Some examples:

- Contracts and documents relating to arrangements made with outside contractors for firefighting equipment and training in the Pacific Northwest;

- Maps and records depicting all former “owl circles” and all locations of other endangered species habitat in the 2 years immediately preceding the Beachie Creek Fire;

- Records declaring the Beachie Creek Fire a Prescribed natural Fire, a Management Ignited Fire or a Wildfire, and all records discussing or relating to that declaration;

- Records illustrating the Suppression Response for the Beachie Creek Fire;

- Records illustrating the Control Strategy for the Beachie Creek Fire;

- Records relating to inputs to and outputs derived from the FLAME computer program or any other predictive computer analysis for the Beachie Creek fire for the period commencing on August 1, 2020, through the date records responsive to this request are provided;

- All Social media posts discussing or describing the Beachie Creek Fire;

- All current Forest Service Manuals in effect immediately preceding the Beachie Creek Fire and effective throughout the Fire Event.

Below is a description of the fire written by the U.S. Forest Service and posted on InciWeb:

“The Beachie Creek Fire was first detected on August 16, 2020 approximately 2 miles south of Jaw Bones flats in rugged terrain deep in the Opal Creek Wilderness. A Type 3 team was ordered to manage the fire on the day it was detected and implemented a full suppression strategy. A hotshot crew tried to hike to the fire within the first 24 hours. They were unable to safely access and engage the fire due to the remote location, steep terrain, thick vegetation and overhead hazards. Fire managers continued to work on gaining access, developing trails, identify lookout locations, exploring options for access and opening up old road systems. The fire was aggressively attacked with helicopters dropping water. A large closure of the Opal Creek area and recreation sites in the Little North Fork corridor was immediately signed and implemented. The fire remained roughly 20 acres for the first week. On August 23rd, the Willamette National Forest ordered a National Incident Management Organization (NIMO) Team to develop a long-term management strategy. This is a high-caliber team which has capacity to do strategic planning. The fire grew slowly but consistently and was roughly 200 acres by September 1st, fueled by hot and dry conditions.

“At the beginning of September, a Type 2 Incident Management Team (PNW Team 13) assumed command of the fire. The fire size was estimated to be about 500 acres on September 6th. On that day, the National Weather Service placed Northwest Oregon under a critical fire weather warning due to the confluence of high temperatures, low humidity and rare summer easterly winds that were predicted to hit upwards of 35 mph in the Portland area on Labor Day. The unique wind event on September 7th created an extreme environment in which the fire was able to accelerate. The winds were 50-75 miles per hour, and the fire growth rate was about 2.77 acres per second in areas of the Beachie Creek fire. This allowed the fire to reach over 130,000 acres in one night. Evacuation levels in the Santiam Canyon area went directly to level 3, which calls for immediate evacuation. Additionally, PNW Team 13 was managing the Beachie Creek Fire from their Incident Command Post established in the community of Gates. That evening, a new fire start began at the Incident Command Post forcing immediate evacuation of the Team and fire personnel. From the night of September 7th, these fires became collectively known as the Santiam Fire. Ultimately, the Santiam Fire name reverted back to Beachie Creek Fire in order to reduce confusion for the communities in the area. The Incident Command Post was re-established in Salem at Chemeketa Community College. At the end of the wind event, the Lionshead Fire also merged with the Beachie Creek Fire having burned through the Mount Jefferson Wilderness.

“After the night of the wind event, the Beachie Creek Fire was managed under unified command by PNW Team 13 and the Oregon State Fire Marshal and the focus shifted to recovery and preservation of life and property. On September 17th, a Type 1 IMT (SW Team 2) assumed command of the fire. Growth on the fire slowed and the fire reached 190,000 acres. A second Type 1 team (PNW 3) took over command of the Beachie Creek Fire, along with the Riverside Fire to the north, on September 29th. Evacuation levels were lowered or removed as fire activity slowed. At the beginning of October, seasonal fall weather moved over the fire producing several inches of rain. During these weeks, a BAER (Burned Area Emergency Response) team assessed the burned landscape and habitats to try to evaluate damage. On October 8th, PNW Team 8, a Type 2 team took over management of the fire. Focus efforts on the ground shifted from suppression and mop-up to suppression repair. On October 14, the fire was downgraded and transitioned command to local Type 3 Southern Cascades team. The acreage topped out at 193,573 acres. Closures remain in place to keep the public safe from hazards like falling trees and ash pits that can remain hot and smolder for months after the wildfire event.”

(end of excerpt)

Our take

The Forest Service is notorious for flagrantly violating the law in regards to the mandatory standards for providing information requested with a FOIA. They have been known to stall for years, or have simply refused to comply. Not every citizen seeking information from their government has a petty cash account with $400 for the filing fee, or the tens of thousands of dollars it could take to pay attorneys for a FOIA lawsuit. Our citizens deserve transparency. However, it also seems unusual to file a lawsuit approximately 26 business days, as Linn County did, after initially submitting the FOIA — just 6 days over the 20-day requirement.

An investigation should determine how much of an effect, if any, fires reportedly started by power lines had on the destruction of private property. It may turn out that some of the structures along the Highway 22 corridor were destroyed by fires sparked by power lines.

If, as appears to be the case, the suppression activity on the fire was less than aggressive for 22 days while it grew to 469 acres, it may have some similarities to the Chimney Tops 2 Fire that burned into Gatlinburg, Tennessee from Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 2016. After creeping along the ground on a hilltop for five days with no suppression activity except for some helicopter drops one afternoon, the 35-acre fire was pushed by strong winds into the city, causing the deaths of 14 people. Over 130 sustained injuries, and 1,684 structures were damaged or destroyed. Approximately 14,000 residents were forced to evacuate.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Kelly.