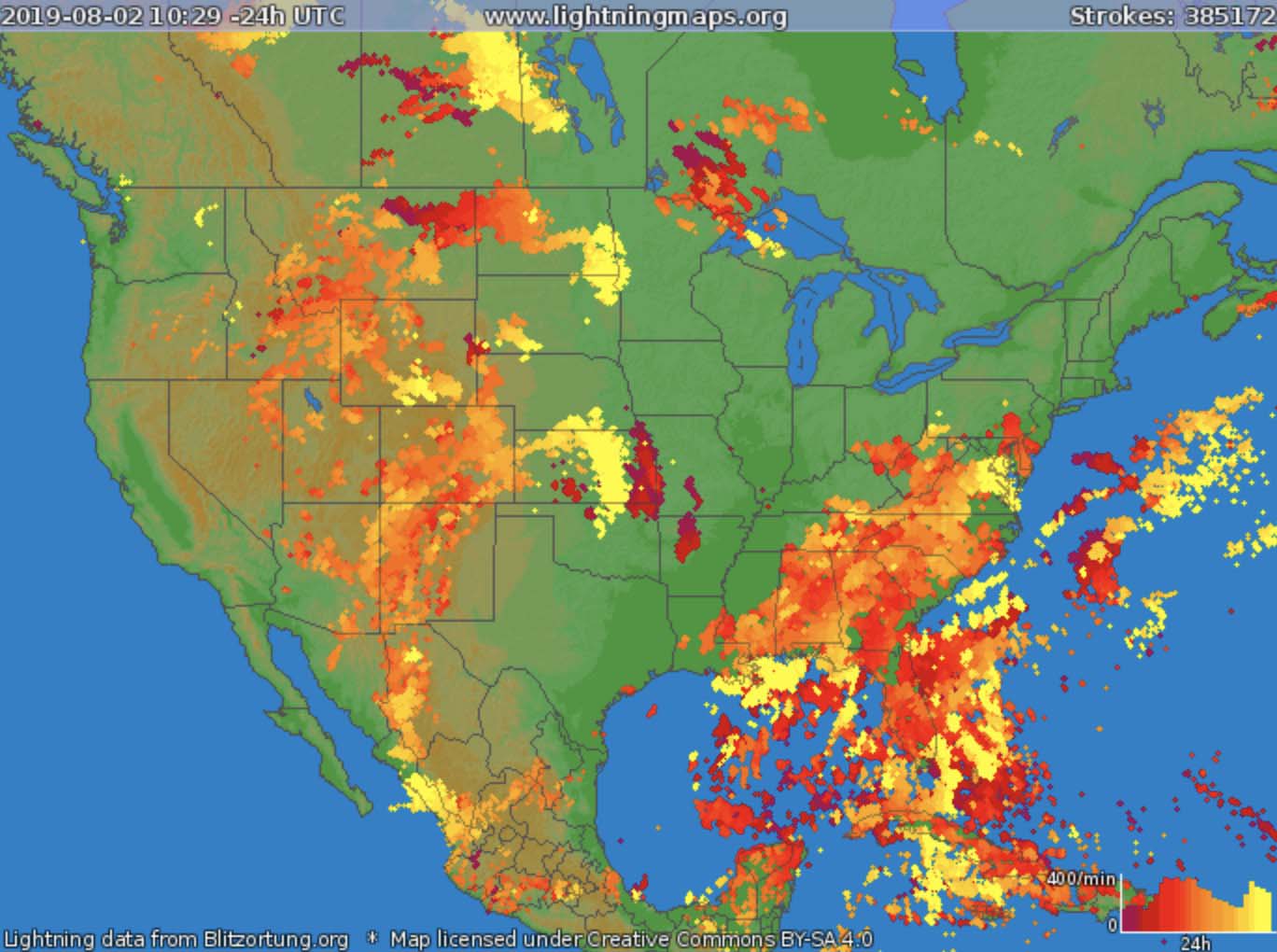

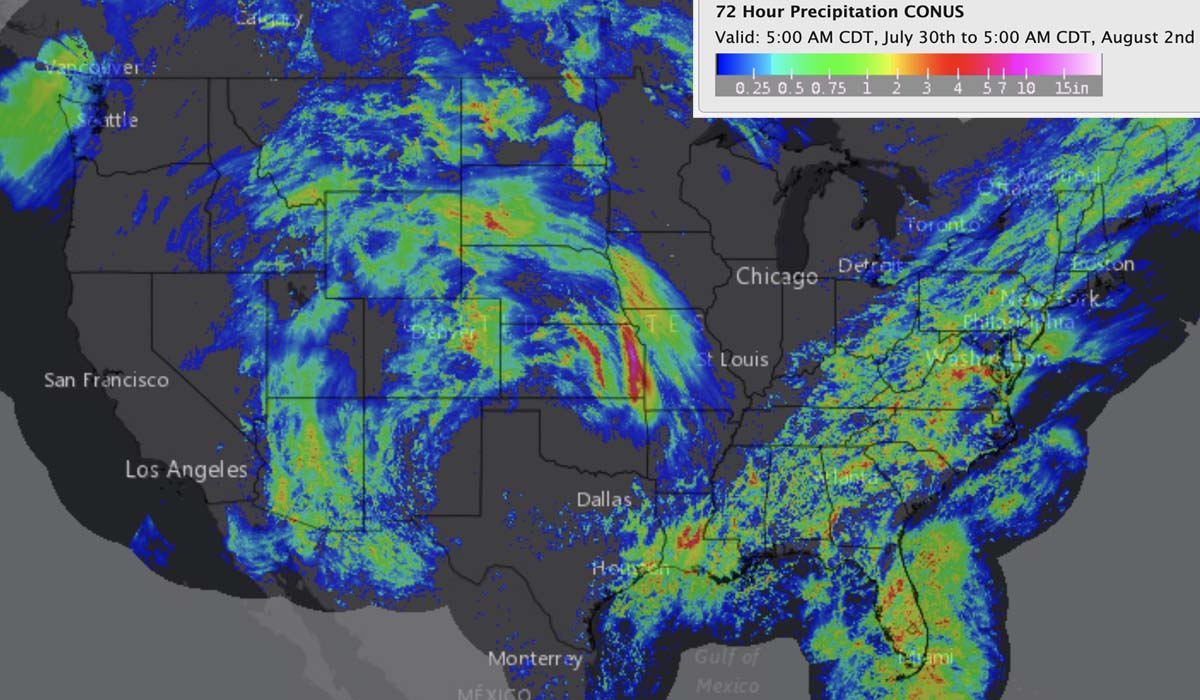

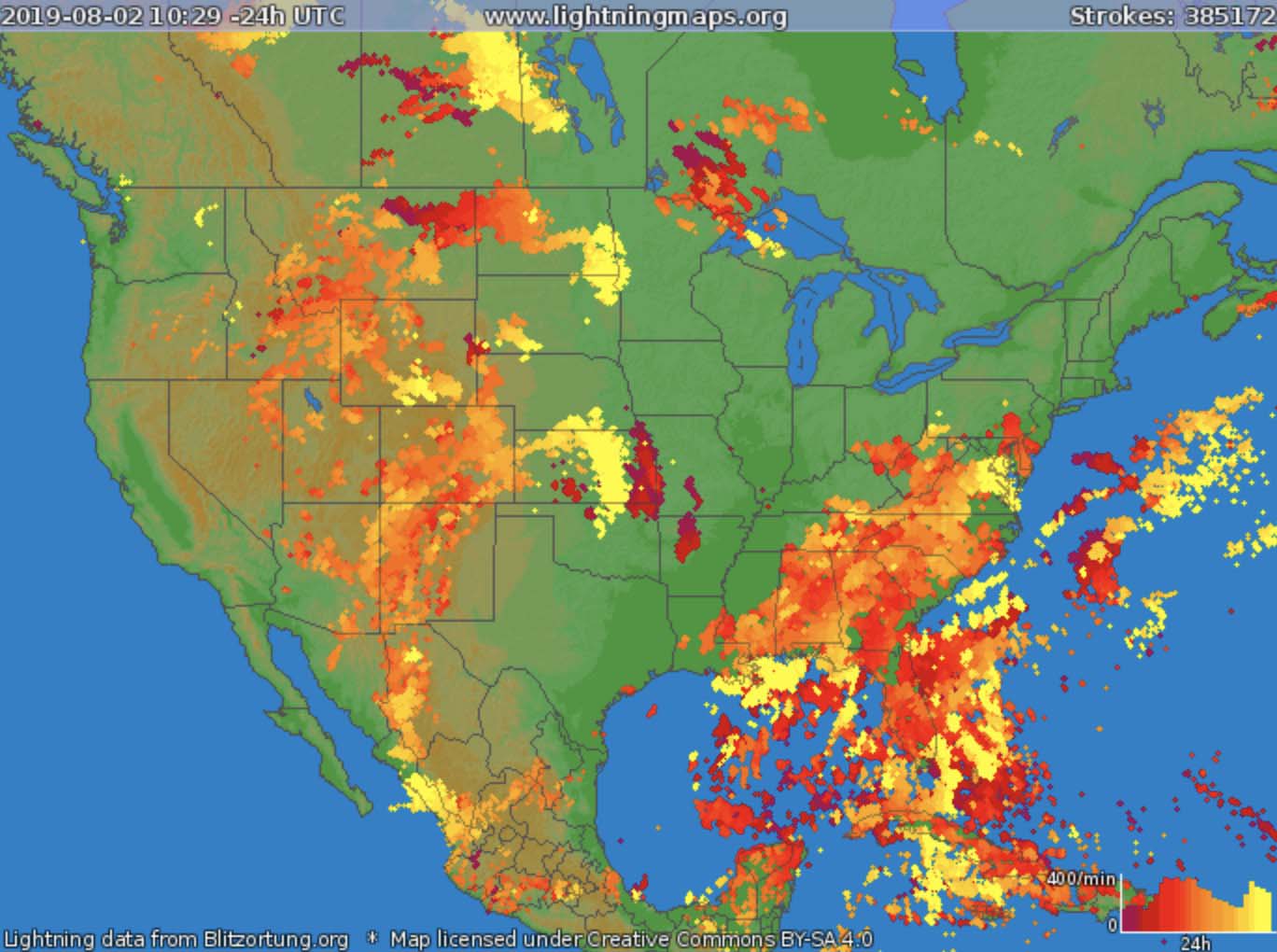

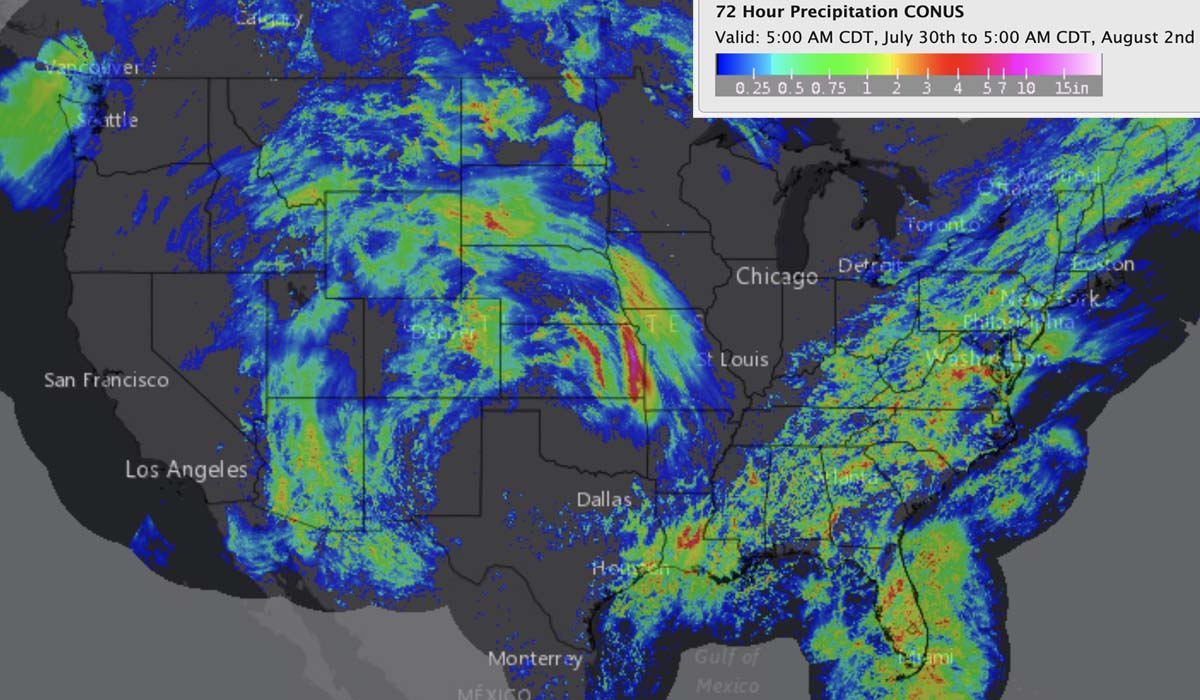

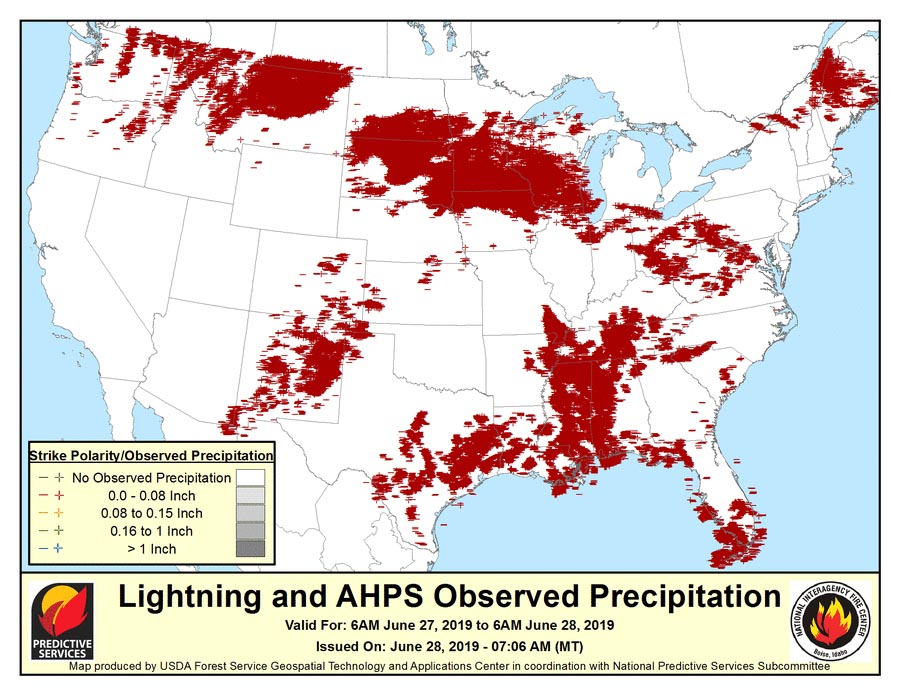

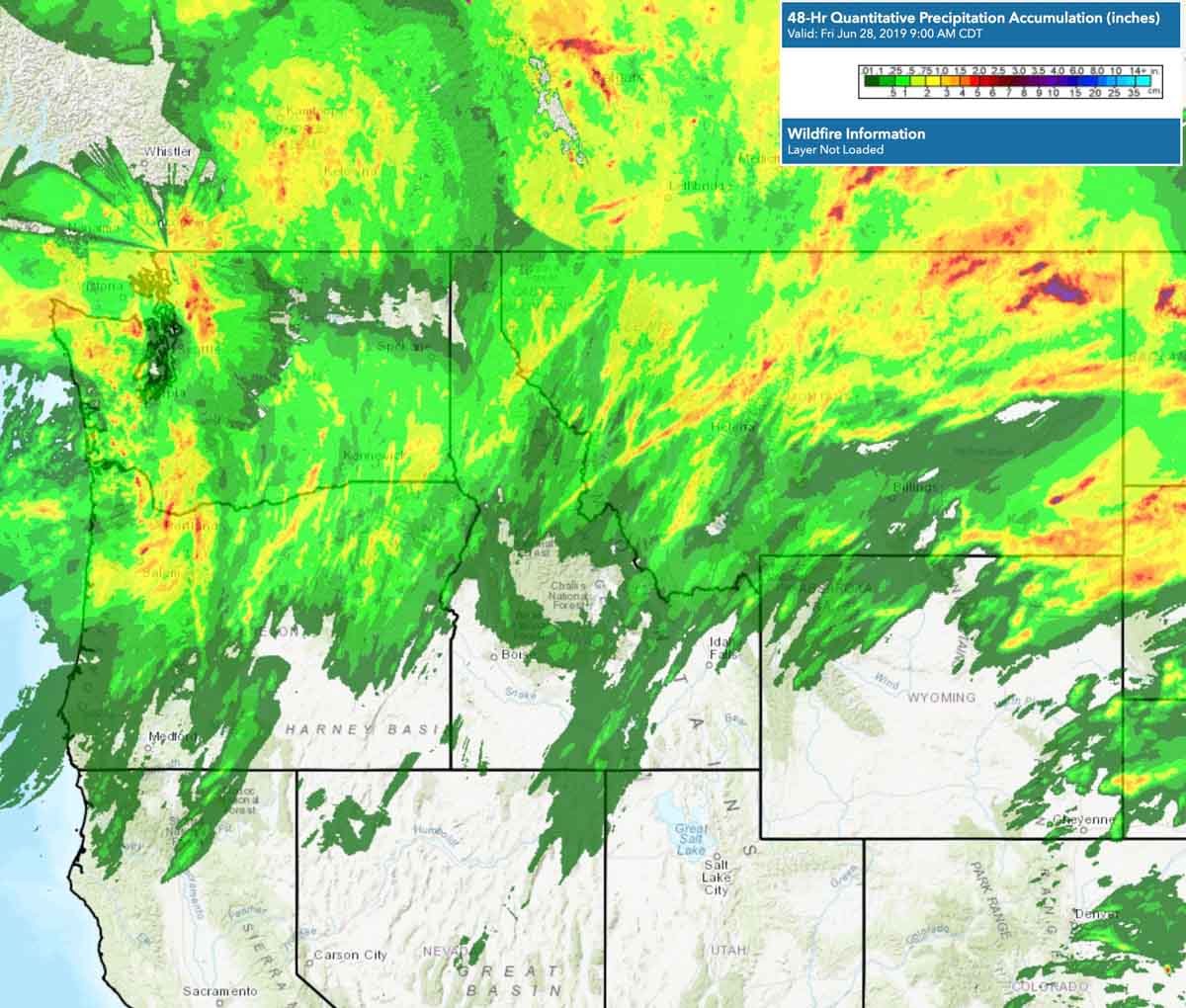

Lightning strikes, above, and accumulated precipitation, below.

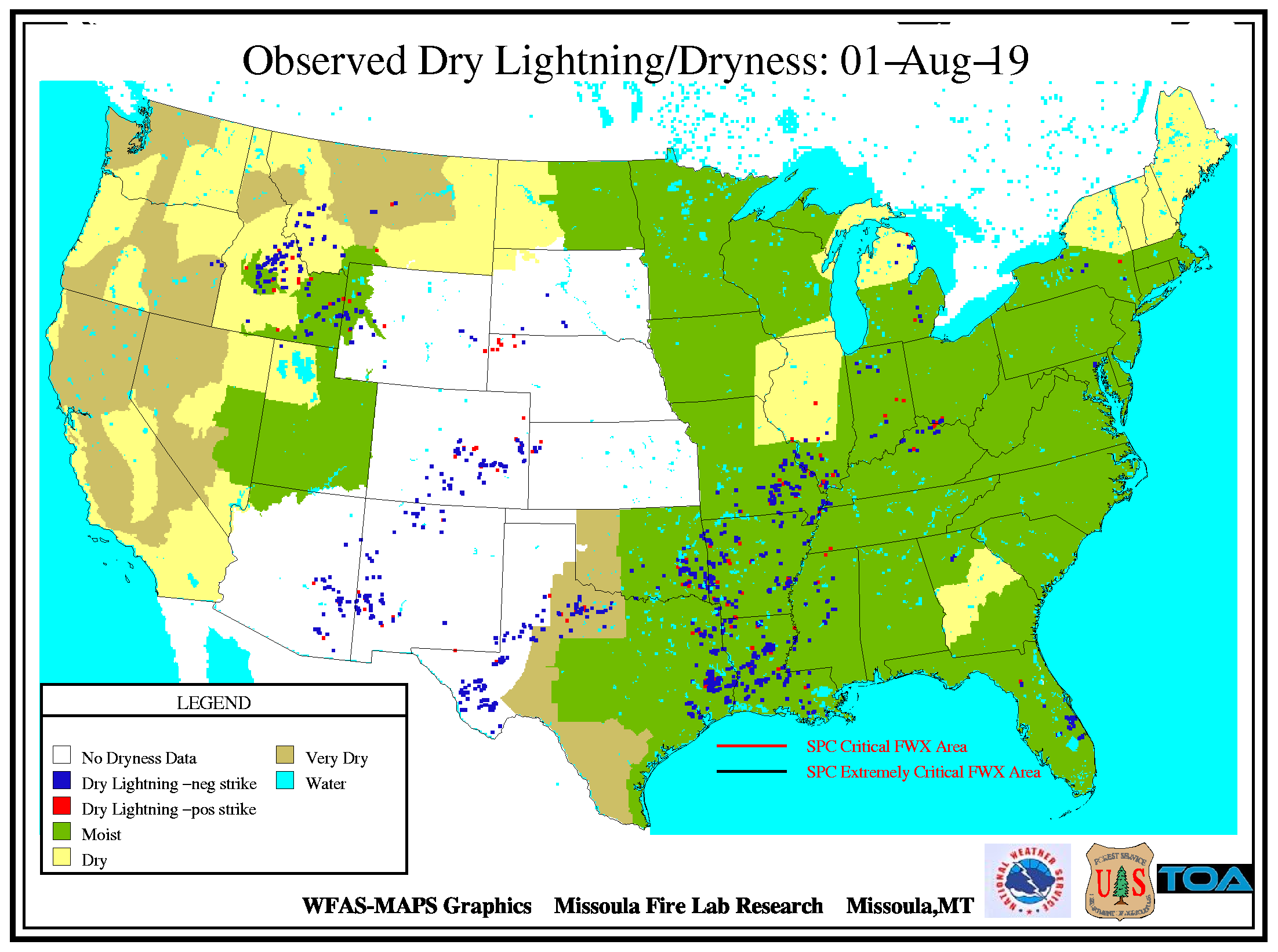

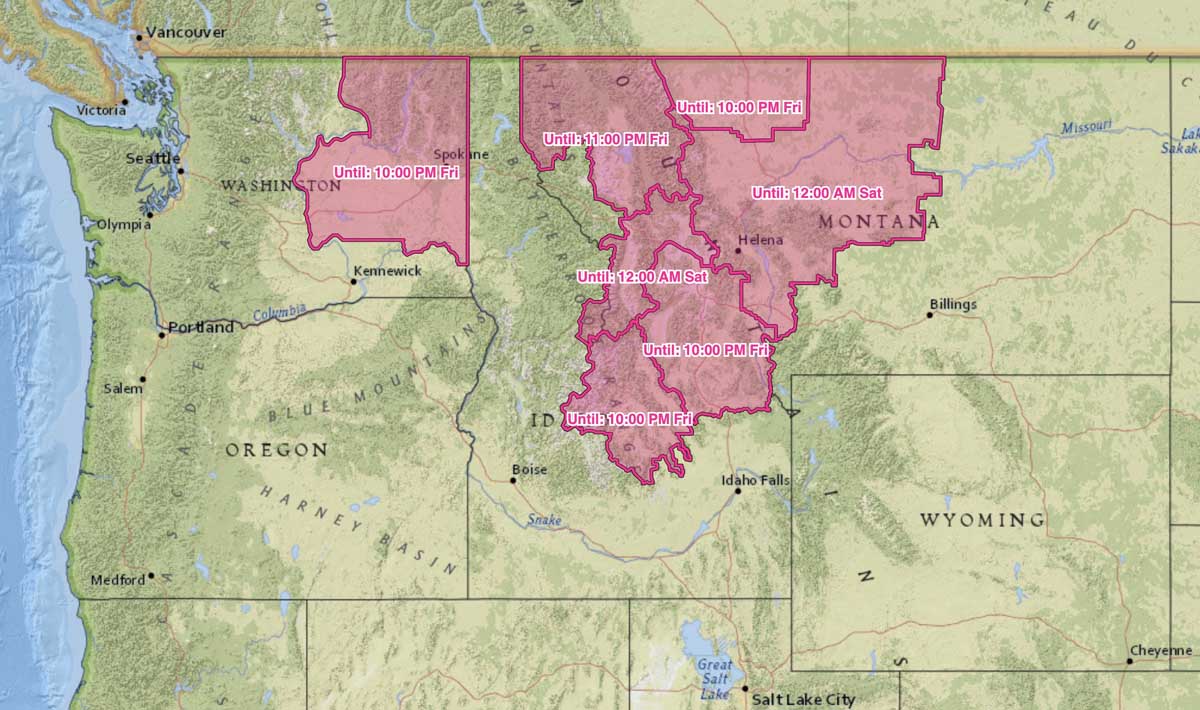

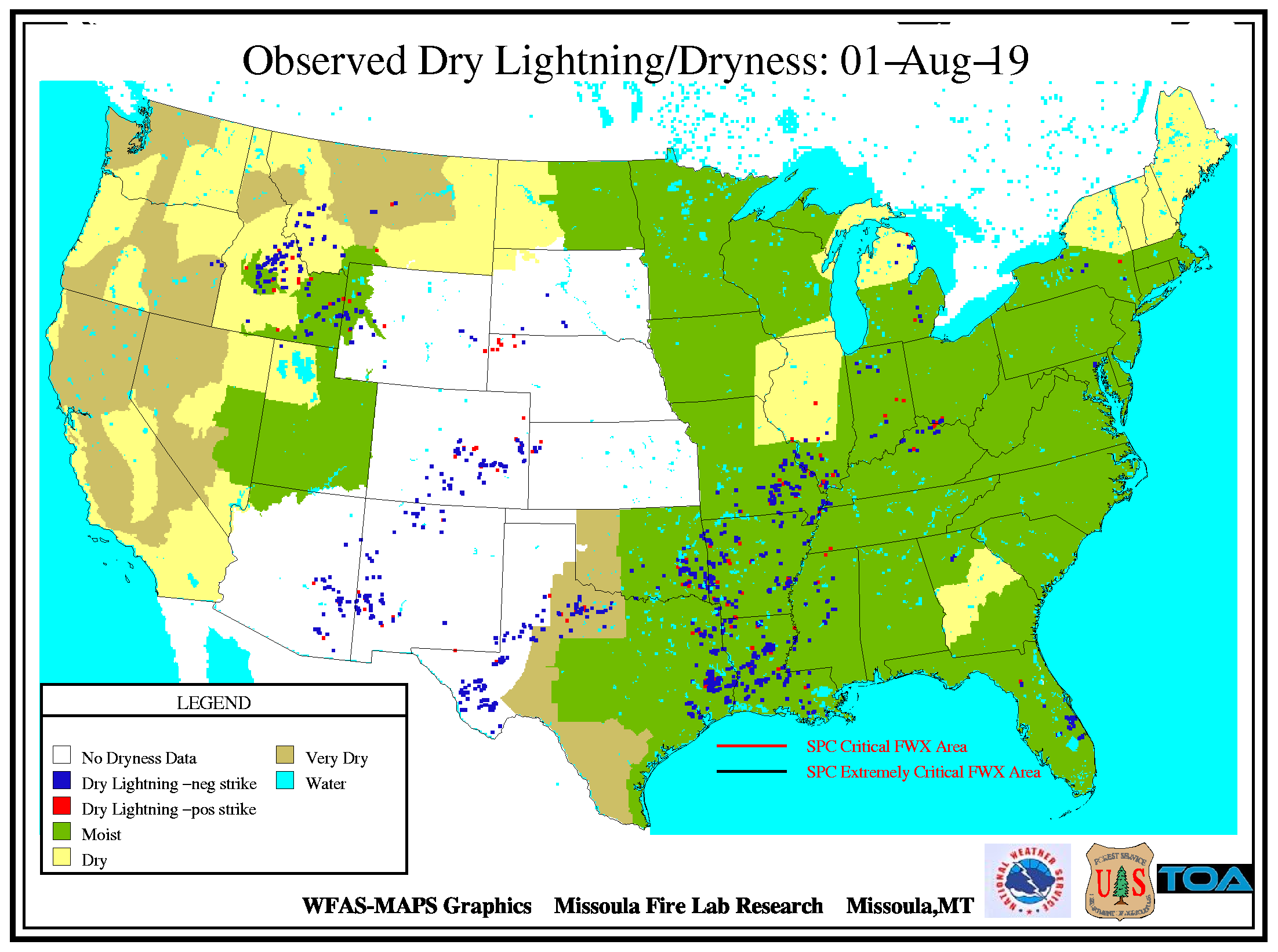

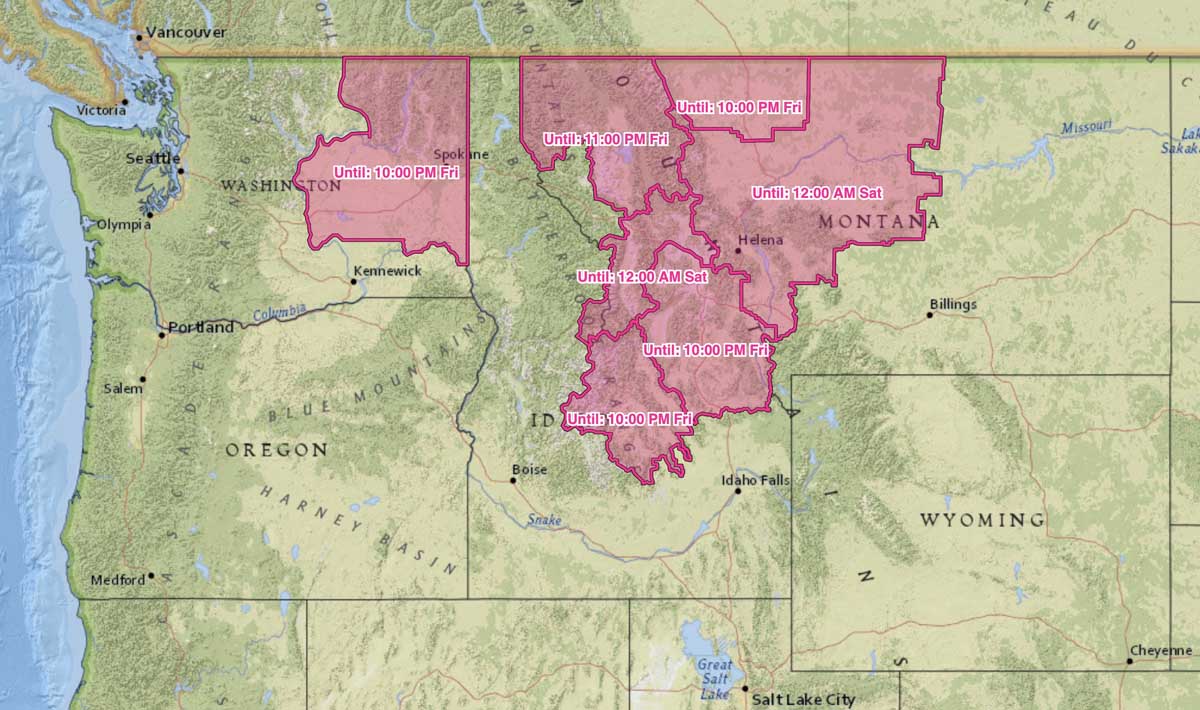

On Friday the Red Flag Warning areas in Washington, Idaho, and southwestern Montana could experience additional lightning with little or no rain.

News and opinion about wildland fire

Lightning strikes, above, and accumulated precipitation, below.

On Friday the Red Flag Warning areas in Washington, Idaho, and southwestern Montana could experience additional lightning with little or no rain.

Thousands of lighting strikes hit Montana, Idaho, Washington, and Oregon Thursday and Thursday night. Much of the area also received at least a little precipitation over the last 48 hours, which could reduce, but not eliminate, the threat of new wildfires.

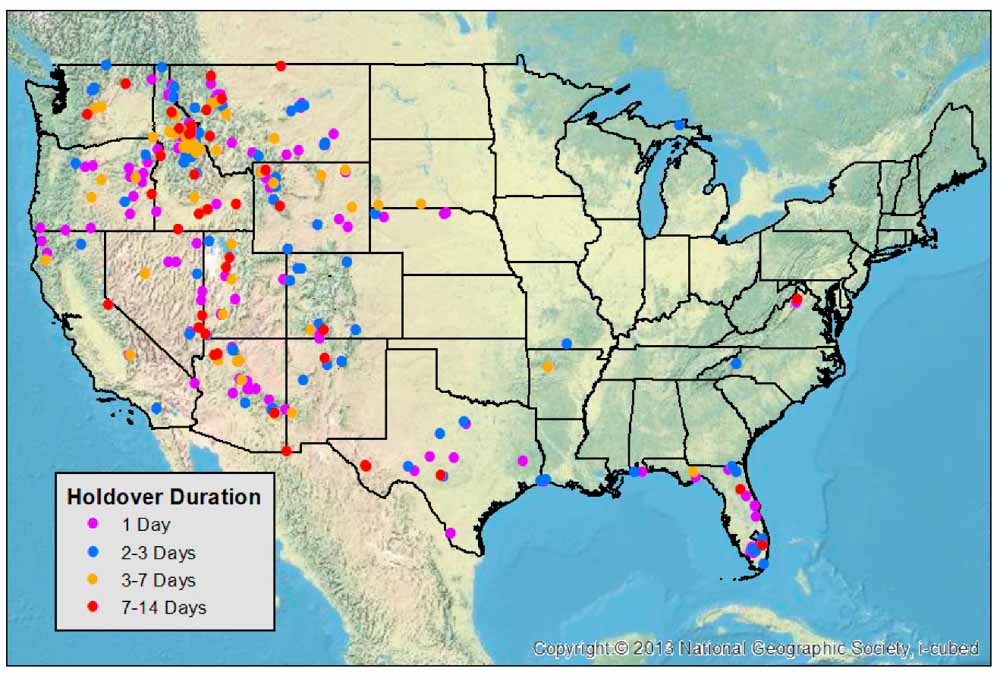

Researchers have found that about a quarter of the fires caused by lightning that grow to more than 4 km² (988 acres) are reported more than a week after they are ignited.

A paper published in the Fire Open Access Journal describes how the National Lightning Detection Network (NLDN) and U.S. Forest Service fire data were used to determine the correlation between lightning strikes and the reported location of lightning-caused wildfires.

The NLDN, which has been used operationally for several decades, consists of 113 sensors across the continental United States and has a reported flash detection efficiency of cloud to ground flashes between 90–95%, with spatial errors that are typically less than 500 meters for the flash data used in the study.

The researchers found, of lightning-caused fires that grew to more than 4 km² (988 acres):

50% reported the same day

71% reported within 3 days

73% reported within 5 days

77% reported within 7 days

Holdover fires that are not reported for days or weeks after the lightning occurs can be problematic for land managers. Shortly after a thunderstorm has left the area, fire detection efforts are often ramped up and may continue in that mode for a few days. Fires that smolder in duff or under snow and suddenly grow can be unexpected. Firefighting resources that may have been staged in anticipation of emerging fires could be released or assigned to active incidents, complicating efforts at quick initial attack with overwhelming force.

Authors of the paper: Christopher J. Schultz, Nicholas J. Nauslar, J. Brent Wachter, Christopher R. Hain, and Jordan R. Bell.

Data was collected in the Southern Sierra Nevada Mountains in California

A California professor’s dissertation has won a prestigious award for her work that determined fires 1,500 years ago in the Sequoia National Forest in Southern California were predominantly ignited by Native Americans rather than by lightning. Until the last 100 years or so most forests in the Western United States had far fewer trees per acre than today. Suppressing fires caused by lightning, arson, and accidents has resulted in overstocked forests that can lead to very large wildfires that threaten lives and property and are very difficult to control.

Prescribed fires can over time lead to stand densities that replicate the pre-Columbian condition, but in modern times the practice has not been widely used in the Western United States at landscape scale.

“We should be taking Native American practices into account,” said Anna Klimaszewski-Patterson, a Sacramento State assistant professor of geography, whose dissertation on the subject recently won the J. Warren Nystrom award from the American Association of Geographers (AAG).

“After all, they are stakeholders who have been here a heck of a lot longer than we have,” she said. “We should probably be looking at their traditions and incorporating them” into forest management.

Klimaszewski-Patterson uses paleoecology – the study of past ecosystems – as well as environmental archaeology and predictive landscape modeling in her current work, which is funded by the National Science Foundation. She won the Nystrom award after presenting her paper at the AAG’s annual meeting in Washington, D.C., earlier this month.

Using computer models and pollen and charcoal records to track changes in the forest over time, she has found that forest composition dating back 1,500 years likely was the result of deliberate burning by Native Americans, rather than natural phenomena such as lightning strikes. Those forests featured wide open spaces, resembling parks.

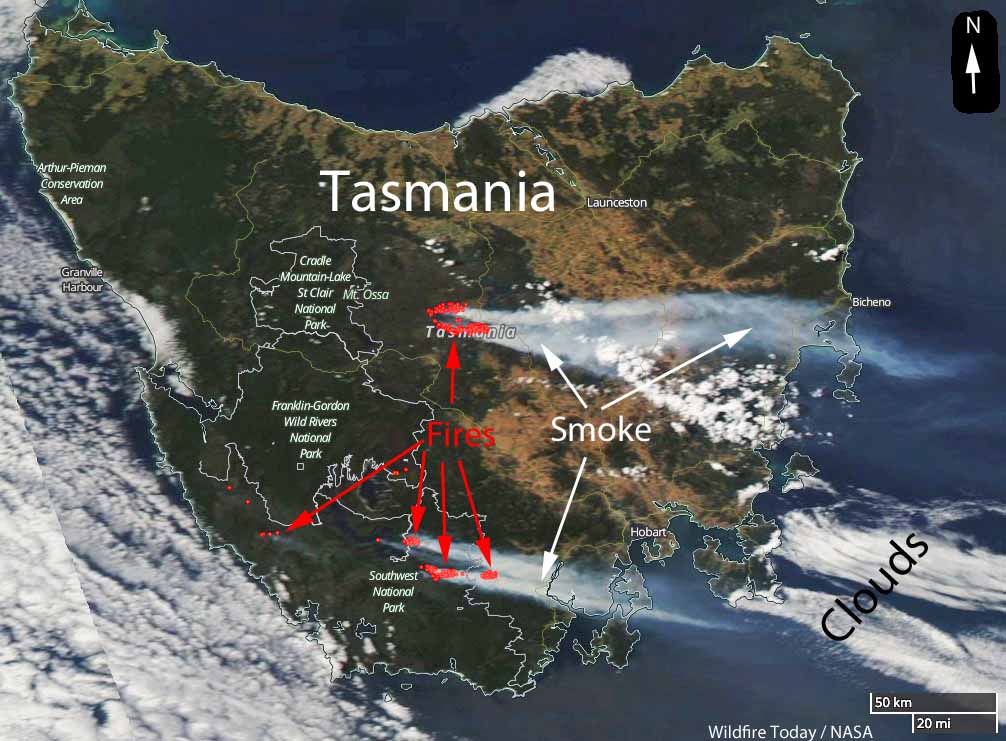

Climate change has already brought alarming change to Tasmania, the huge island south of the Australian mainland. Until recently it was assumed that the climate differences would not be massive since it was thought by some that the ocean surrounding the island would not be heating as quickly as it was in other areas.

Now the southwest area of the state, the heart of its world heritage area, is being described as dying — the rainforest and heathlands are beginning to disappear. The nearby seas, it turns out, are warming at two to three times the global rate.

Richard Flanagan writes about this issue in an opinion article at The Guardian. Below is an excerpt:

…Then there was the startlingly new phenomenon of widespread dry lightning storms. Almost unknown in Tasmania until this century they had increased exponentially since 2000, leading to a greatly increased rate of fire in a rapidly drying south-west. Compounding all this, winds were also growing in duration, further drying the environment and fuelling the fires’ spread and ferocity.

Such a future would see these fires destroy Tasmania’s globally unique rainforests and mesmerizing alpine heathlands. Unlike mainland eucalyptus forest these ecosystems do not regenerate after fire: they would vanish forever. Tasmania’s world heritage area was our Great Barrier Reef, and, like the Great Barrier Reef, it seemed doomed by climate change.

Later [Prof Peter] Davies [an eminent water scientist] took me on a research trip into a remote part of the south-west to show me the deeply upsetting sight of an area that was once peatland and forest and was now, after repeated burning, wet gravel. The news was hard to comprehend – the enemies of Tasmania’s wild lands had always had local addresses: the Hydro Electricity Commission, Gunns, various tourism ventures. They could be named and they could be fought, and, in some cases, beaten.

Six weeks ago, the future that Davies and others had been predicting arrived in Tasmania. Lightning strikes ignited what would become known as the Gell River fire in the island’s south-west. In later weeks more lightning strikes led to more fires, every major one of which is still burning.

Extreme heat on Friday in Victoria, Australia combined with strong winds and low humidity caused a bushfire 10 km (6 miles) north of Timbarra to grow from 300 hectares (740 acres) to approximately 10,522 hectares (26,000 acres). Lighting ignited the fire on January 16 and in an odd twist, extreme fire behavior Friday created hundreds of lightning strikes around a massive pyrocumulus cloud that rose to 38,000 feet while igniting additional fires.

The temperature at the top of the cloud was -55°C (-67°F) according to the Victoria Bureau of Meteorology.

Large bushfire in #EastGippsland producing a huge plume of smoke this afternoon stretching over eastern Bass Strait. Check out the satellite picture at https://t.co/9md40P2b4k pic.twitter.com/5ceZV5nf0T

— Bureau of Meteorology, Victoria (@BOM_Vic) January 25, 2019

Friday evening the weather changed substantially, bringing in cool, moist air that slowed the spread of the fire. Officials say due to the size and difficult topography, it will be weeks before it can be completely contained.