In 1993, District Manager John Koehler was in the midst of a shift in popular fire management practices. In his position with the Florida Forest Service (then the Division of Forestry) he’d noticed a new trend developing among the country’s wildfire managers, but he found there was little data to support their claims. So he decided to conduct a study to either verify or debunk the usefulness of prescribed burns.

Koehler wasn’t the first to gain interest in whether the historical practice of prescribed burning was as effective as people claimed. Fire Scientist Robert Martin, in his 1988 study, found that prescribed burning reduced the number of acres burned per wildfire, but said the practice’s effect on wildfire occurrence was “at best, speculative.” Forester James Kerr Brown, in his 1989 study, said a prescribed burning program would not have prevented the disastrous Yellowstone fires that had burned the year before.

Koehler was less than impressed by either study. He wanted to learn whether prescribed fires held quantifiable, tangible benefits – which neither study supplied. To compile hard data, Koehler used nine years’ worth of Florida Forest Service fire statistics to determine whether prescribed burns were affecting the frequency and size of wildfires at all. His study would go on to produce the hard data he was looking for, concluding that in every area where prescribed burns occurred, decreases were recorded in the total number of wildfires, the number of acres burned, and the average number of acres burned per wildfire.

“Prescribed burning will not eliminate wildfires, but this practice does reduce the threat posed from wildfires,” Koehler said.

At the end of his study, he recommended more research focused on quantifying benefits of prescribed burning as a prevention tool. Fast-forward 30 years, and Koehler would get his wish after a team of researchers on the other side of the country completed one of the most comprehensive examinations of prescribed burns’ effect on future wildfires.

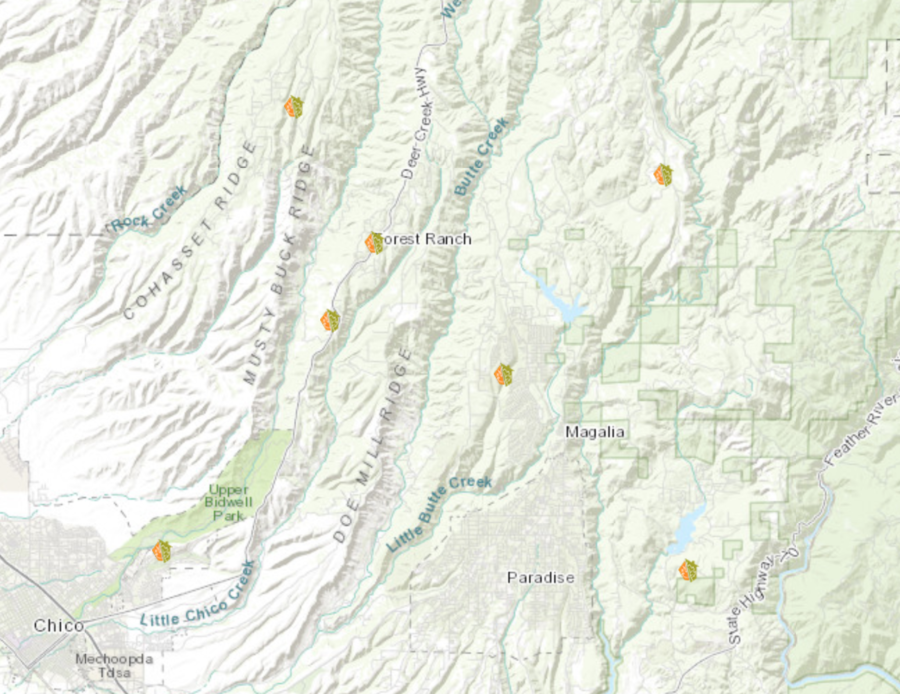

The new research, “Low-intensity fires mitigate the risk of high-intensity wildfires in California’s forests,” was published in the journal Science by Biostatistician Xiao Wu from Columbia University and a team of Stanford researchers. In the study, the team analyzed 20 years of satellite data on fire activity across more than 62,000 miles of California forests to determine whether intentional low-intensity burns mitigate the consequences of the increasing frequency of severe wildfires.

Their conclusions were the same that Koehler had heard wildfire managers espousing decades before: prescribed

burns help prevent future wildfires.

In conifer forests, they found, areas that have recently burned at low intensity are 64 percent less likely to burn at high intensity in the following year relative to unburned synthetic control areas – and this protective effect against high-intensity fires persists for at least 6 years.

The study not only found prescribed burns widely successful in California, but also showed that they’re a necessary practice vital to conifer forests’ health, something Native American tradition has known for centuries.

The study does not shy away from referencing previous case studies that indicate frequent and low-intensity fires were the norm before the forceful removal of numerous Native American tribes from California. Previous research from Ecologist Alan Taylor shows that fire regime changes over the past 400 years likely resulted from socioecological changes rather than climate changes. Fire Scientist Scott Stephens found around 4.4 million acres of California had burned annually before 1800, in part helped by Native American cultural burning. Geographer Clarke Knight determined that indigenous burning practices promoted long-term forest stability in the forests of California’s Klamath Mountains for at least one millennium.

“The resilience of western North American forests depends critically on the presence of fire at intervals and at intensities that approximate presuppression and precolonial conditions that existed prior to the extirpation of Native Americans from ancestral territories in California,” Wu wrote.

The research led the study’s authors to recommend a continuation of the policy transition from fire suppression to restoration – through the usage of prescribed fire, cultural burning, and managed wildfire. The maximum benefits a prescribed fire program can yield, however, are dependent on whether the practice becomes a sustained tradition. If sustained, prescribed burning could have an ongoing protective effect on nearly 4,000 square miles of California’s forests.

Getting to that point would require many more resources. As pointed out in Fire Scientist Crystal Kolden’s 2018 research, management practices in the West have still failed to wholeheartedly adopt and increase prescribed burning despite calls from scientists and policy experts, including the 30-year-old call from Koehler.

The result is the continual compounding

of the ongoing fire deficit.

“Federal funding for prescribed fire and other fuel reduction activities has been drastically depleted over the past two decades as large wildfires force federal agencies to expend allocated funds on suppression rather than prevention,” said Kolden.

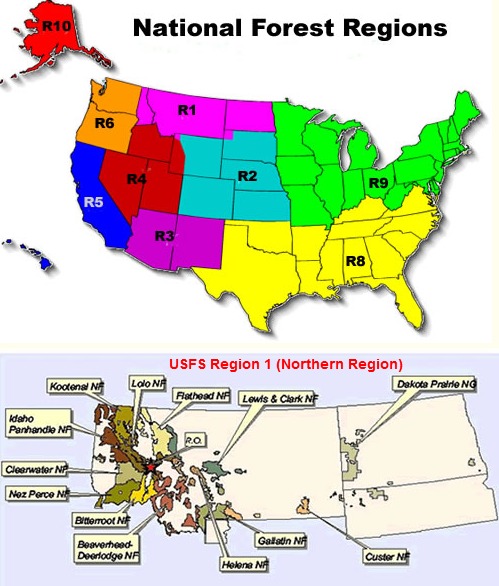

She also gave a well-deserved shoutout to fire managers in the Southeast U.S., crediting them with accomplishing double the number of prescribed burns compared with the entire rest of the U.S. between 1998 and 2018. “This may be one of many reasons the Southeastern states have experienced far fewer wildfire disasters relative to the Western U.S. in recent years,” Kolden said.

Even as the USFS and other federal agencies continue to tout prescribed burns in their national strategies, it won’t be until the agencies collectively create policy changes and budgetary allocations sufficient that prescribed burning is used at a scale in which it can create meaningful prevention. Without those meaningful changes, the wealth of prescribed burn research clearly shows that more catastrophic wildfire disasters are inevitable.