Quebec and Ontario’s environmentally crucial boreal forests had a tough wildfire season in 2023. The provinces had 12.8 million and 1.1 million acres burn, respectively.

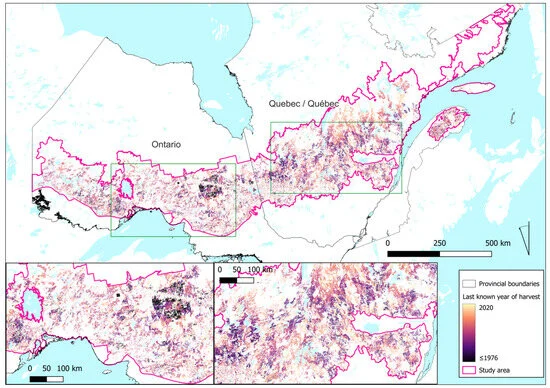

The 44 million acres burned by wildfires across Canada have been attributed mainly to abnormal drought and high temperatures, but a new study is pointing to another possible factor: the planting of millions of acres of immature trees after widespread logging. A recent study published by researchers at Australia’s Griffith University found more than 35 million acres of Canada’s forests have been lost to logging since 1976, including 20 million acres in Quebec and 14 million acres in Ontario.

The “loss” wasn’t caused by deforestation, which is “land that has been cleared of trees and permanently converted to another use” under Canada’s definition. Rather, the forest has been lost to forest degradation, or the conversion of naturally regenerating forest to plantations of planted trees.

“The Canadian Government claims that its forests have been managed according to the principles of sustainable forest management for many years,” the researchers said, “yet this notion of sustainability is tied mainly to maximizing wood production and ensuring the regeneration of commercially desirable tree species following logging,”

The decrease in the land area of older, more resilient forests across both Quebec and Ontario — and their subsequent replacement with immature trees — both lowered overall forest biodiversity and increased the prevalence of disturbances (wildfire, insect infestations, disease spread) over time.

“Logging has significantly increased the rate of disturbances in this region,” the report said. “This decrease in older forests when compared with historical natural conditions is accompanied by the resulting decline in structural attributes — such as large live and dead standing trees and coarse woody debris associated with older forests — which negatively affects biodiversity.”

The full study is online [HERE].

Quebec and Ontario’s environmentally crucial boreal forests had a tough wildfire season in 2023. The provinces had 12.8 million and 1.1 million acres burn, respectively.

The 44 million acres burned by wildfires across Canada have been attributed mainly to abnormal drought and high temperatures, but a new study is pointing to another possible factor: the planting of millions of acres of immature trees after widespread logging. A recent study published by researchers at Australia’s Griffith University found more than 35 million acres of Canada’s forests have been lost to logging since 1976, including 20 million acres in Quebec and 14 million acres in Ontario.