Australia is considering it

Updated September 2, 2020 | 8:58 a.m. PDT

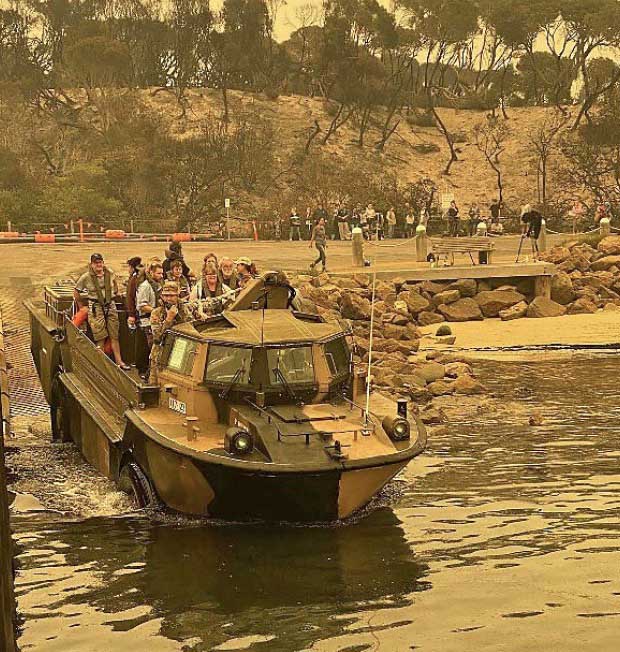

Early last week the United States requested help from Australia and Canada in battling the wildfires in California and other states. The National Multi-Agency Coordinating Group, through the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), asked Canada for four to five 20-person hand crews and requested 55 overhead personnel from Australia.

The three 20-person crews from Quebec will be arriving in Boise Wednesday September 2. They will receive a briefing orientation and participate in fire shelter deployment training. After a one-night rest in Boise, the crews will fly to Reno, Nevada and board ground transportation to their fire assignment on the North Complex in California. The North Complex consists of numerous lightning fires being managed as one incident on the Plumas National Forest.

As for the status of the request for 55 overhead positions from down under, “Australia is on hold for now,” Ms. Cobb said. “They are assessing the need for the types of personnel being requested as our fire situation evolves.”

Australia is approaching the beginning of their 2020-2021 summer bushfire season.

From The Australian Broadcasting Corporation:

The ABC understands anyone who wants to go to California will have to pass strict health tests and age will be taken into consideration because of COVID-19.

Those who go to California will have to quarantine for two weeks when they return to Australia, which [Australasian Fire and Emergency Service Authorities Council CEO Stuart] Ellis said he expected would play a role in deciding who goes.

“That needs to be factored into each (fire) commissioner’s consideration of their people’s availability,” he said.

“Not only will they be absent for the period they are in the United States, but they will also need to spend two weeks in quarantine on return to Australia.”

Queensland will not send anyone because the state is about to enter their fire season and Victoria will not assist due to the health crisis. New South Wales, the ACT, and Western Australia are considering their options.

The final decision is up to each state and territory, but Ellis said he is optimistic Australia will either meet or come close to the requested number.

California has asked for help to arrive by September 6.

It is possible that the fire authorities in Australia may be in a very awkward position. During their extraordinarily busy 2019-2020 summer bushfire season, the U.S. deployed more than 200 U.S. Forest Service and Department of the Interior wildland fire staff to the Australian Bushfire response.

Firefighters in Australia asked to travel to America could think they would be entering a more risky environment by accepting an assignment where the COVID-19 death rate is 21 times higher per 100,000 population — 2.63 in Australia compared to 56.12 in the U.S. The death rate in Canada is less than half of the U.S. rate, 24.75.

Australia and New Zealand sent 44 fire specialists to assist the United States in 2008, and 68 in 2015. They may have helped out in other years also.

The California National Guard and active duty soldiers from the U.S. Army are being mobilized for firefighting duty in the U.S.