August 11, 2020 | 1 p.m. MDT

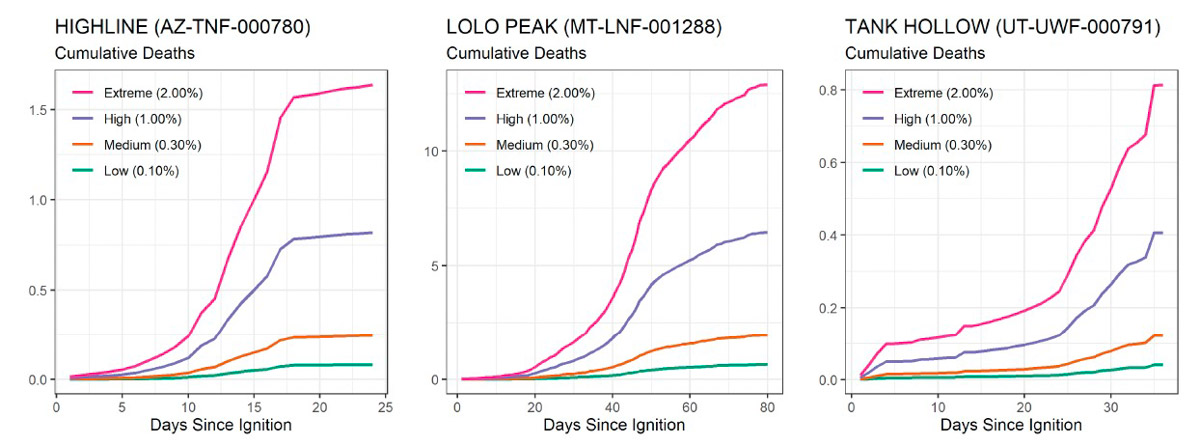

Researchers developed a COVID-19 epidemic model to highlight the risks posed by the disease during wildland fire incidents. A paper published August 1, 2020 details how they started with actual mobilization data from the Resource Ordering and Status System (ROSS) for three 2017 wildfires that had different characteristics — the Highline Fire, which burned for much of the summer but the personnel peaked early in the effort; the Lolo Peak Fire, which spanned July through September and had a relatively symmetric mobilization and demobilization phase; and the Tank Hollow Fire, which was shorter than the other two, and had fewer personnel throughout the incident.

The variables that were modeled included the number of infected persons arriving at a fire, the rate of secondary infections caused by an infected person, infection fatality rate, and the number of people assigned to the fire each day.

There are also many other variables that are difficult or impossible to account for, such as social distancing at the incident, protocols followed by personnel in the weeks before the assignment, how much time they spend at fire camp, mode of travel to and during the incident, wearing of masks, testing before and during the incident, working remotely, and others.

Below is an excerpt from the study:

“Models are, by definition, an abstraction of reality and are subject to the accuracy of the parameters. Wildfires and the COVID-19 pandemic are each complex dynamic phenomenon, and the combination of the two produces great uncertainty. Therefore, we stress the limits of our model and highlight the qualitative results of the analysis rather than the estimated numbers.

“In this study, we focused on two sources of case growth on an incident. The first is the introduction of infection by personnel arriving on an incident. As the fire grows and the incident becomes more complex, resource orders will be filled by available personnel, some of whom may come from other counties or states. Given the variation in the COVID-19 prevalence around the country at any given point in time, the firefighters from different areas will introduce variable risk to the camp. While current policies require or request symptomatic individuals to report their conditions and inform supervisors, evidence suggests that many infected people may experience very mild symptoms. These asymptomatic individuals may remain infectious for weeks, perhaps posing the greatest risk of infection through a camp. The combination of exposure risk posed by the high turnover of personnel coming from a large number of places in concert with the exposure risk due to non-quarantined infectious individuals highlights the potential merits of developing testing strategies for early identification, which could include testing asymptomatic individuals without known or suspected exposure. The utility of such testing strategies is conditioned by the availability, timeliness, and reliability of viral tests, and the optimal testing strategy design could be the subject of future research.

“The second source of case growth on an incident that we examined was the spread among personnel while assigned to the fire. In the event that personnel arrive at an incident exposed or infected, their level of interaction with others will determine the rate of transmission within the camp. The rate of transmission will depend on the level of interaction between the personnel at the incident and the nature of those interactions. Under normal circumstances, personnel may gather in large groups, for example, for briefings or meals. These interactions are similar to potentially infectious interactions in the general public that public health agencies have deemed ill-advised. Some of these interactions could be made less risky using current social distancing and mitigation recommendations; for example, masks appear to provide a barrier to the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Recognizing that a range of mitigations is already being planned or put into place by incident management personnel, these analyses provide a proxy for a business-as-usual baseline as a point of comparison.

“We studied two types of interventions corresponding to the two types of source growth identified above: the screening of personnel arriving at the incident to address the case growth by the entry of the virus and the spread from non-quarantined infectious individuals, and social distancing measures within the fire camp to address the case growth from the spread among individuals in the camp. While both interventions mitigate transmission and lead to fewer cases, screening measures are relatively more effective on shorter incidents with a frequent resource turn over. In contrast, social distancing measures are relatively more effective on prolonged campaigns where most of the cases are due to transmission within the community.”

The researchers found that a large, long-duration fire with a hundreds of personnel is likely to have more infected individuals and fatalities than shorter-duration incidents with fewer individuals. Under COVID-19 conditions, a fire like the 2017 Lolo Peak Fire south of Missoula could have, according to their modeling, from less than 1 or up to 13 fatalities from the disease.

The study was conducted by Matthew P. Thompson, Jude Bayham, and Erin Belval. It was supported by Colorado State University and the U.S. Forest Service. (Download the study; large 1.9 Mb file.)