In mid-March the U.S. Forest Service cancelled or postponed all ignitions of prescribed fires in their Rocky Mountain Region (comprised of five states), the 13 states in the Southern Region, and California. Back then we reached out to the Forest Service’s Washington Office to ask, “Nationwide, have all prescribed fires been cancelled or postponed because of COVID-19?” On March 23 the Lead Public Affairs Specialist for the FS in Washington, Kaari Carpenter, confirmed that they were:

Our mission-critical work, such as suppressing wildfires, and other public service responsibilities, will continue within appropriate risk management strategies, current guidance of the Centers for Disease Control, and local health and safety guidelines. All new ignitions for prescribed fire have been postponed until further notice.

After hearing that prescribed fires on Forest Service lands might be allowed again, we checked with Stanton Florea, who recently transferred from a public information position in the California regional office to a similar position for the Forest Service at the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise that had been vacant. After a week, on April 30 we received what was described as “our response to your question”, which presumably came from or was approved by a government office in Washington.

The USDA Forest Service has not issued agency-wide direction to pause prescribed burning activities. Each region has been making their own decisions in terms of conducting prescribed burning activities.

Last week the Forest Service’s Pacific Southwest Region (California) included this announcement in a newsletter:

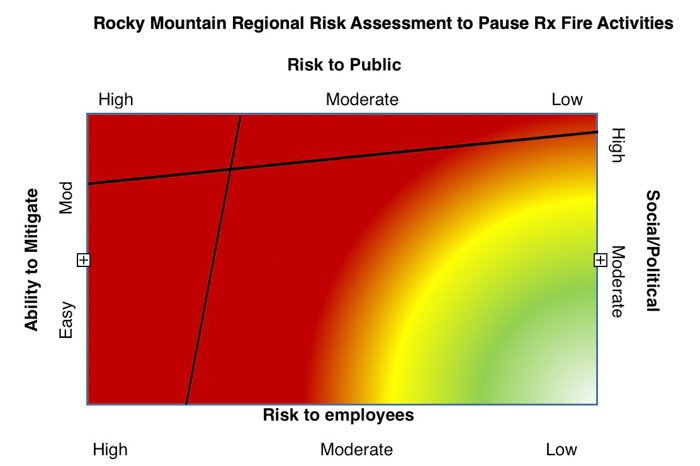

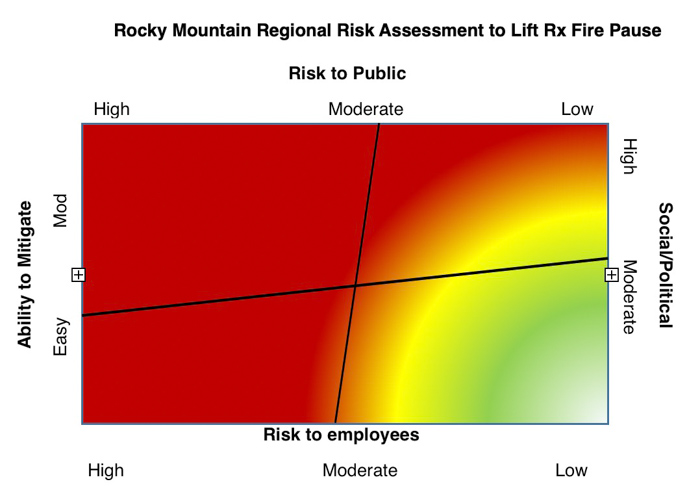

In March, the Rocky Mountain Region compiled a thoughtful analysis of the risk of conducting prescribed fires, taking many factors into consideration. The chart at the top of the page was the risk at the time that led to the decision to postpone the projects in the region. Below is the assessment of the conditions they established that would be necessary to allow prescribed fires to be restored after the COVID-19 pandemic has improved.

If the Forest Service is going to use the above analysis to justify reinstating prescribed fire ignitions, then they will have decided that:

- The ability to mitigate the risk changed from Moderate to Easy;

- Risk to the public changed from High/Moderate to Moderate;

- Social/Political moved from High to Moderate, and

- Risk to employees changed from High/Moderate to Moderate.

The experience of suppressing a small to moderate-sized wildfire in Arizona on April 17 proved that managing the fire, which included the extraction of a firefighter with a broken ankle, proved to be much more complex than before the COVID-19 pandemic. If the fire had been large and the injury life-threatening, the difficulties would have been even more problematic.

The Bureau of Land Management has been conducting prescribed fires for weeks at least, and on April 29 the National Park Service initiated the first ever broadcast prescribed fire in Mount Rushmore National Memorial in preparation for Donald Trump’s fireworks show on July 3.

The New York Times reports that the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection plans to burn roughly 3,200 acres over the next two months.

Below is an excerpt from their article, which addresses the effects of prescribed fire smoke during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Officials at CAL FIRE said they were taking steps to limit the health effects from their controlled burns, such as analyzing wind conditions to make sure smoke will not blow toward hospitals. Each burn, which can range in size from a few acres to several hundred, also requires advance approval from local air quality management boards, which in turn typically consult with local public health agencies.

Officials from several air quality boards and public health agencies downplayed the harm that controlled burns could inflict on those infected with Covid-19. “If they’re fighting for every breath, they’re in the hospital and not exposed to the smoky air,” said Lisa Almaguer, a spokeswoman for the Butte County public health department. “If they have moderate to severe symptoms then they’re home and in bed.”