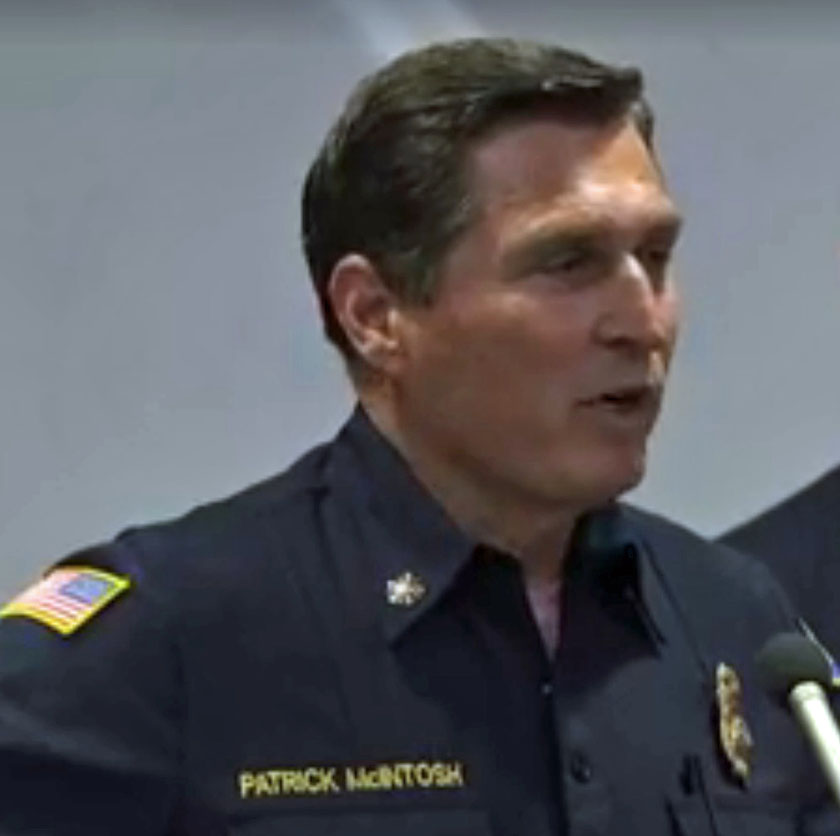

In a news conference Wednesday the interim Chief of the Orange County Fire Authority (OCFA) revealed the timeline for actions taken, and not taken, when the Canyon 2 Fire was first reported on October 9, 2017. The fire eventually burned 9,200 acres, destroyed 15 homes and damaged 45 others. For the last week the OCFA has been criticized over reports the initial response to the fire was delayed.

Chief Patrick McIntosh said Wednesday “flames and smoke” were first reported in a 911 call at 8:32 a.m. near the 91 freeway and the 241 Toll Road interchange in Orange County, California. The nearest fire station, Station 53, was not staffed because about three hours earlier the wildland engine was dispatched with four others from the OCFA to one of the fires in Northern California. Support personnel at the station were asked if they could see smoke. They went outside and seven minutes later reported they could only see what appeared to be ash blowing off the previous Canyon Fire.

At 9:27 and 9:28 two more reports came in of smoke near the 91 Freeway and Gypsum Canyon which is in the same area as the earlier report. At 9:31 one engine from Station 32 and a helicopter were dispatched.

At 9:41 personnel at Station 53 said they could see a column of smoke which appeared to be building and recommended additional resources.

Chief McIntosh said the OCFA initiated a “High Watershed Dispatch” at 9:43 which included 7 engines, 2 helicopters, 2 water tenders, 2 dozers, 1 hand crew, 2 air tankers, and one fixed wing air attack.

The Orange County Register earlier this week reported on some details about the response of aerial resources:

At 9:52 a.m., the first OCFA helicopter lifted off from Fullerton Airport. But a second helicopter – which a Fire Authority memo dated Oct. 8 said was required because of “red flag warnings” in effect that week – did not leave and had to be dispatched again five minutes later.

The fixed-wing planes that would have been part of a “medium level” response were not en route until 10:19 a.m., from Hemet, 51 minutes after the fire was reported.

There are also questions about the helicopters operated by the Orange County Sheriff’s Department that were not used on the fire. The ships reportedly have water dropping capabilities but may or may not be certified by state or federal agencies to work on wildfires. The OCFA and the Sheriff’s office have been feuding about the responsibilities of their two helicopter fleets. Historically the Sheriff’s fleet has taken the lead for searches, while the OCFA has handled rescues. In the last year, however, the Sheriff has been poaching responses to rescues resulting in multiple helicopters appearing over the same incident potentially causing airspace conflicts and confusion.

In the news conference the Chief said he will recommend to the County Board of Supervisors an independent review be conducted of how the fire was handled.

“My heart tells me we could have done something different”, the Chief said, but he wants to wait for the review before saying exactly what that should have been.

“Our commitment to you and to our community is full disclosure, full transparency, we have nothing to hide as an agency” the Chief continued. “If there are things that need to be done better and different, we will do those.”

In Fullerton at 8:53 a.m. the day the fire started, about 9 miles northwest of the fire, the winds were calm and the relative humidity was 68 percent. But by 12:53 p.m. the humidity had dropped to 5 percent and a Santa Ana wind was blowing from the east at 24 mph gusting to 35 mph — conditions that could cause a wildfire to spread rapidly.

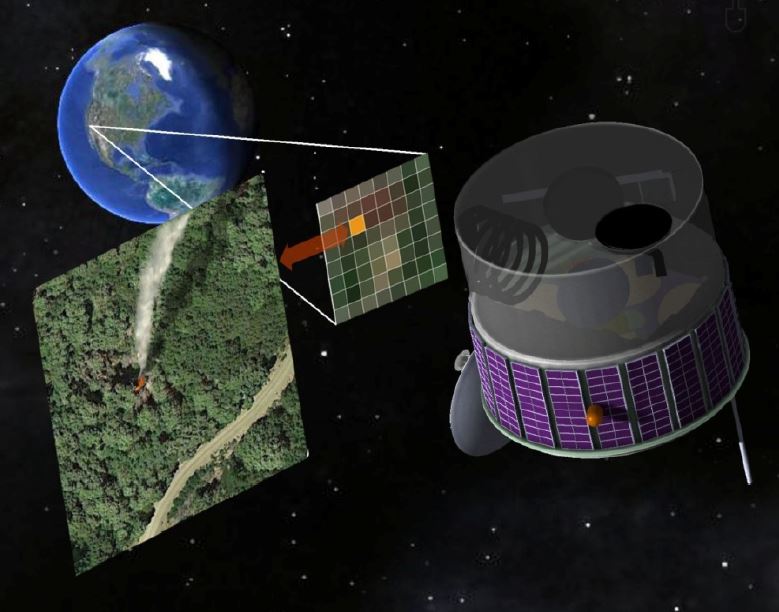

We have been writing since 2012 about how a prompt, aggressive attack may prevent a small fire from becoming something much more serious.

Sometimes a timid initial attack can lead to the loss of structures. The U.S. Forest Service and other agencies spent a small amount of money on the anemic and delayed initial attack of the 2012 Waldo Canyon Fire. But later, homeowners and insurance companies had to spend $353 million for the property that was destroyed in Colorado Springs. Other times a weak response can result in a large fire that kills many people, such as the 1994 South Canyon and the 2013 Yarnell Hill Fires which killed a total of 31 firefighters. The Waldo Canyon Fire also killed two residents. And let us not forget the Chimney Tops 2 Fire. Very little ground-based action occurred during the first five days which then spread into the eastern Tennessee city of Gatlinburg killing 14 people, forcing 14,000 to evacuate, destroying or damaging 2,400 structures, and blackening 17,000 acres.

Thanks and a tip of the hat go out to Mike.

Typos or errors, report them HERE.