September 24, 2020 | 8:10 a.m. MDT

A bill has been introduced in the U.S. Senate that would make large sums of money available to increase the number of acres treated with prescribed fire (also known as controlled burns).

It has been fashionable during the last two years to blame “forest management” for the large, devastating wildfires that have burned thousands of homes in California. According to a 2015 report by the Congressional Research Service the federal government manages 46 percent of the land in California. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection manages or has fire protection responsibility for about 30 percent.

Research conducted in 2019 to identify barriers to conducting prescribed fires found that in the 11 western states the primary reasons cited were lack of adequate capacity and funding, along with a need for greater leadership direction and incentives. Barriers related to policy requirements tended to be significant only in specific locations or situations, such as smoke regulations in the Pacific Northwest or protecting specific threatened and endangered species.

The National Prescribed Fire Act of 2020, Senate Bill 4625, which was introduced last week by Senator Ron Wyden of Oregon and two cosponsors, would help address the capacity issue by appropriating $300 million for both the Forest Service and the Department of the Interior (DOI) to plan, prepare, and conduct controlled burns on federal, state, and private lands. It would also provide $10 million for controlled burns on county, state and private land that are at high risk of burning in a wildfire. Additionally, the bill establishes an incentive program that would provide $100,000 to a State, county, and Federal agency for any controlled burns larger than 50,000 acres. (Summary and text of the bill)

In order to carry out the projects, the legislation would establish a workforce development program at the Forest Service and Department of the Interior to develop, train, and hire prescribed fire practitioners, and creates employment programs for Tribes, veterans, women, and those formerly incarcerated.

In an effort to address air quality control barriers, the bill “Requires state air quality agencies to use current laws and regulations to allow larger controlled burns, and give states more flexibility in winter months to conduct controlled burns that reduce catastrophic smoke events in the summer.” The legislation will allow some prescribed fire projects larger than 1,000 acres to be exempt from air quality regulations.

Our Take

Appropriating more funds and hiring additional personnel for conducting prescribed fires could definitely result in more acres treated. If the bill passes, it would be a large step in the right direction. It is notable that the bill specifically mentions hiring those who were formerly incarcerated. Those who served time for non-violent offenses often deserve another chance, especially if they learned the firefighting trade on a state or county inmate fire crew.

There are many benefits of prescribed fires, including more control over the adverse health effects of smoke, improving forest health, and returning fire to dependent ecosystems.

But it gets complicated when prescribed fire is expected to “…help prevent the blistering and destructive infernos destroying homes, businesses and livelihoods”, as cited in a release issued last week by the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources.

One provision of the bill is poorly worded and is confusing. In Section 102 it is either saying that no later than September 30, 2022 every unit of the USFS, FWS, NPS, and BIA must conduct a prescribed fire larger than 100 acres, possibly only applying to units west of the 100th meridian. Or, it might be interpreted as meaning each unit larger than 100 acres must conduct at least one prescribed fire. But either way it is ridiculous and arbitrary. Some 100-acre units might never be suitable for prescribed fire. Planning to use fire as a tool is based on science and the determination that treating an area with fire is PRESCRIBED in order to accomplish a number of specific objectives, not well-meaning but possibly detrimental legislation.

Scenario #1, Moderate fire conditions

There is no doubt that if a wildfire is spreading under moderate conditions of fuels and weather (especially wind), when the blaze moves into an area previously visited by any kind of fire the rate of spread, intensity, and resistance to control will decrease. Firefighters will have a better chance of stopping it at that location. The size of that earlier fire footprint will be a factor in the effectiveness of stopping the entire fire, since the wildfire may burn through, around, or over it by spotting. The availability of firefighting resources to quickly take advantage of what may be a temporary reduction in intensity is also critical. Unless the prescribed fire occurred within the last year or so there is usually adequate fuel to carry a fire (such as grass, leaves, or dead and down woody fuel) depending on the vegetation type and time of year. It is much like using fire retardant dropped by air tankers. Under ideal conditions, the viscous liquid will slow the spread long enough for firefighters on the ground to move in and put out the fire in that area. If those resources are not available, the blaze may eventually burn through or around the retardant.

Scenario #2, Extreme fire conditions

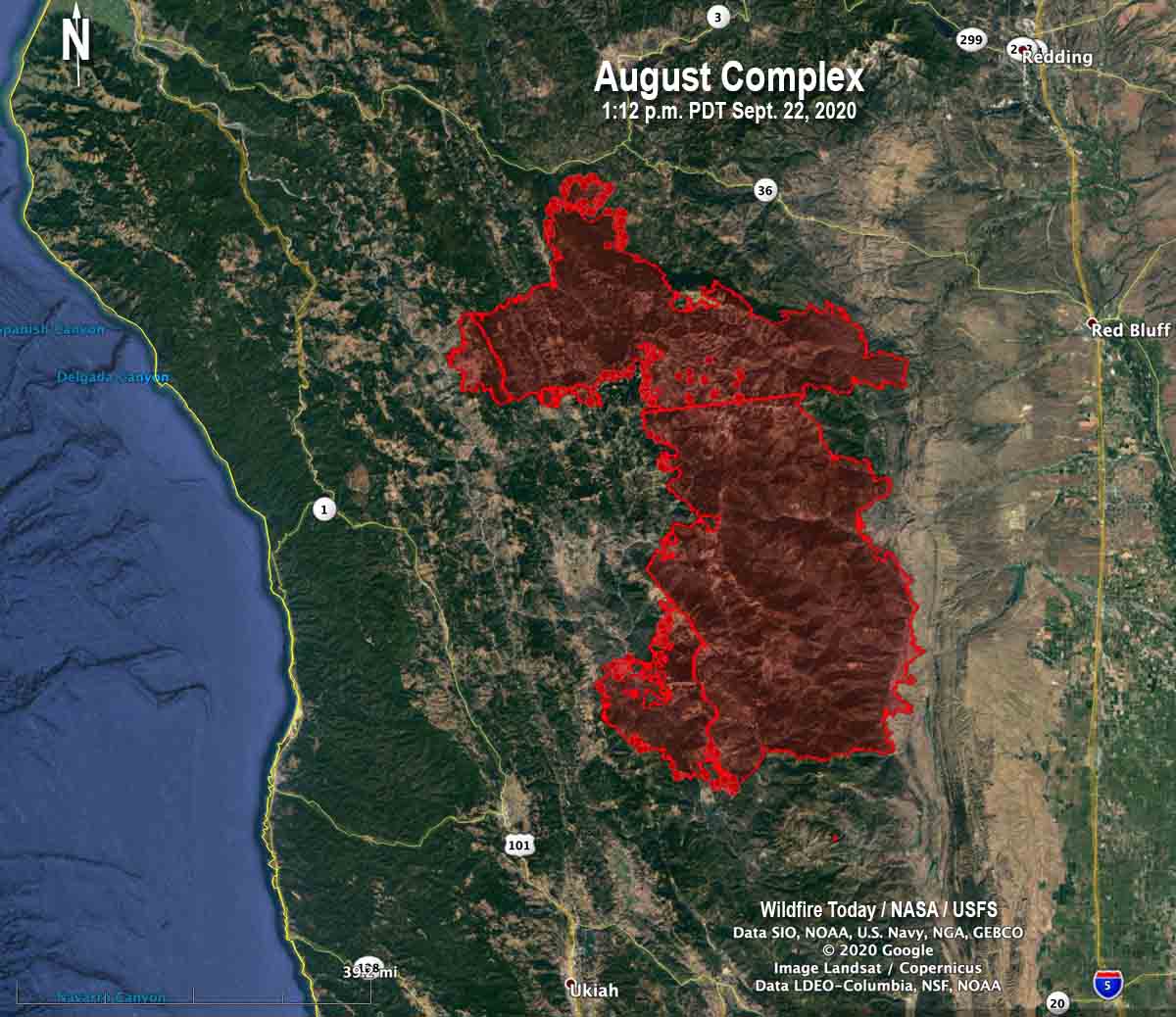

The wildfires that burn hundreds or thousands of homes usually occur during extreme conditions. What the most disastrous fires have in common is drought, low fuel moisture, low relative humidity, and most importantly, strong wind. In the last few weeks in California and Oregon we have seen blazes under those conditions spread for dozens of miles in 24 hours.

Rich McCrea, the Fire Behavior Analyst on the recent North Complex near Quincy, CA, said the wind on September 8 pushed the fire right through areas in forests that had been clear cut, running 30 miles in about 18 hours.

We can’t log our way out of the fire problem.

On September 8, 2020 the Almeda Drive Fire burned 3,200 acres in Southern Oregon — it was not a huge fire, but there were huge losses. The 40 to 45 mph wind aligned with the Interstate 5 corridor as it burned like a blowtorch for 8 miles, starting north of Ashland and tearing through the cities of Talent and Phoenix. Approximately 2,357 structures were destroyed — but not all by a massive flaming front. Burning embers carried up to thousands of feet by the fire landed in receptive fuels near or on some structures, setting them alight.

What can be done to reduce fire losses?

Jack Cohen is a retired U.S. Forest Service Research fire scientist who has spent years determining how structures ignite during extreme wildfires. In a September 21, 2020 article he wrote for Wildfire Today with Dave Strohmaier, they addressed how homes ignite during extreme wildfires.

“Surprisingly, research has shown that home ignitions during extreme wildfires result from conditions local to a home. A home’s ignition vulnerabilities in relation to nearby burning materials within 100 feet principally determine home ignitions. This area of a home and its immediate surroundings is called the home ignition zone (HIZ). Typically, lofted burning embers initiate ignitions within the HIZ – to homes directly and nearby flammables leading to homes. Although an intense wildfire can loft firebrands more than one-half mile to start fires, the minuscule local conditions where the burning embers land and accumulate determine ignitions. Importantly, most home destruction during extreme wildfires occurs hours after the wildfire has ceased intense burning near the community; the residential fuels – homes, other structures, and vegetation – continue fire spread within the community.

“Uncontrollable extreme wildfires are inevitable, however, by reducing home ignition potential within the HIZ we can create ignition resistant homes and communities. Thus, community wildfire risk should be defined as a home ignition problem, not a wildfire control problem.”

"Community wildfire risk should be defined as a home ignition problem, not a wildfire control problem." Jack Cohen and Dave Strohmaier.

Again, prescribed fire has many benefits to forests and ecosystems, and Congress would be doing the right thing to substantially increase its funding.

But in order to “…help prevent the blistering and destructive infernos destroying homes, businesses and livelihoods”, we need to think outside the box — look at where the actual problem presents itself. The HIZ.

I asked Mr. Cohen for his reaction to the proposed legislation that he and I were not aware of when the September 21 article was published.

“Ignition resistant homes, and collectively communities, can be readily created by eliminating and reducing ignition vulnerabilities within the HIZ,” Mr. Cohen wrote in an email. “This enables the prevention of wildland-urban fire disasters without necessarily controlling extreme wildfires. Ironically, ignition resistant homes and communities can facilitate appropriate ecological fire management using prescribed burning. The potential destruction of homes from escaped prescribed burns is arguably a principal obstacle for restoring fire as an appropriate ecological factor. Therefore, it is unlikely that ecologically significant prescribed burning at landscape scales will occur without ignition resistant homes and communities.”

Here are some suggestions that could be considered for funding along with an enhanced prescribed fire program.

- Provide grants to homeowners that are in areas with high risk from wildland fires. Pay a portion of the costs of improvements or retrofits to structures and the nearby vegetation to make the property more fire resistant. This could include the cost of removing some of the trees in order to have the crowns at least 18 feet apart if they are within 30 feet of the structures — many homeowners can’t afford the cost of complete tree removal.

- Cities and counties could establish systems and procedures for property owners to easily dispose of the vegetation and debris they remove.

- Hire crews that can physically help property owners reduce the fuels near their homes when it would be difficult for them to do it themselves.

- Provide grants to cities and counties to improve evacuation capability and planning, to create community safety zones for sheltering as a fire approaches, and to build or improve emergency water supplies to be used by firefighters.

Our article “Six things that need to be done to protect fire-prone communities” has even more ideas.