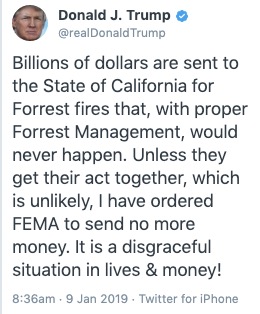

This morning when I saw a tweet that appeared to be from President Trump that threatened to “send no more money” to California at first I thought it was sent by a parody account. The fact that “Forrest” was misspelled, not once but twice, and capitalized, made it seem unlikely that the leader of the free world could misspell the word. Then I saw the little blue checkmark, indicating that it is a verified account.

I made a screengrab of the tweet in case it was deleted, and shortly after that, it was. Here is the original version:

About 50 minutes after sending the Forrest tweet he deleted the first version and sent a revised copy that was exactly the same, but this time spelling “Forest fires” correctly.

If our President is going to try to influence how state or federal land management agencies manage their forests, he needs to know enough about the issue to spell the word correctly.

Mr. Trump has made the threat of cutting off funds to California related to wildfires on other occasions, including November 10, 2018 and October 17, 2018.

On November 27 Mr. Trump expanded on his wildfire management opinions in a lengthy interview with two reporters from the Washington Post, Philip Rucker and Josh Dawsey. Below is a portion of what he said to them about fires, according to the Post:

I was watching the firemen and they’re raking brush — you know the tumbleweed and brush and all this stuff that’s growing underneath. It’s on fire and they’re raking it working so hard, and they’re raking all this stuff. If that was raked in the beginning, there’d be nothing to catch on fire.

It sounds like the firefighters were mopping up, using tools to stir duff and burning materials so that it can cool, or so water can be more efficiently applied. He also has advocated raking the forest floors. But reducing the threat of wildfires is much more complicated than raking. On December 28, 2018 I wrote about some of the complexities involved in preventing homes from burning during a wildfire, and the fact that home owners, planners, and local jurisdictions have the responsibility to design structures, infrastructure, and communities that can live with wildfires. Treating fuels near residential areas using mechanical methods or prescribed burning is also necessary. More logging is not the answer.

According to a 2015 report by the Congressional Research Service the federal government manages 46 percent of the land in California. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection manages or has fire protection responsibility for about 30 percent.

In August the President tweeted about California,“Must also tree clear to stop fire spreading!”

Below is an excerpt from an article in the Sacramento Bee on August 7, 2018:

The Trump administration’s own budget request for the current fiscal year and the coming one proposed slashing tens of millions of dollars from the Department of Interior and U.S. Forest Service budgets dedicated to the kind of tree clearing and other forest management work experts say is needed. And it’s just one example of how the federal government is still not prioritizing fire mitigation to the scale that is needed, according to forestry experts.

“I think for a number of years the feds were more ahead of this dilemma, at least in discussions,” said Scott Stephens, a professor of fire science at the University of California, Berkeley. But “I have to say right now, I think the state is moving ahead. It’s certainly being more innovative, it’s doing more policy work.”