Maps are a great way to communicate with a public that may be starving for information about an ongoing fire, or to inform them about conditions that could lead to more fires. They can provide information very quickly — if thoughtfully created.

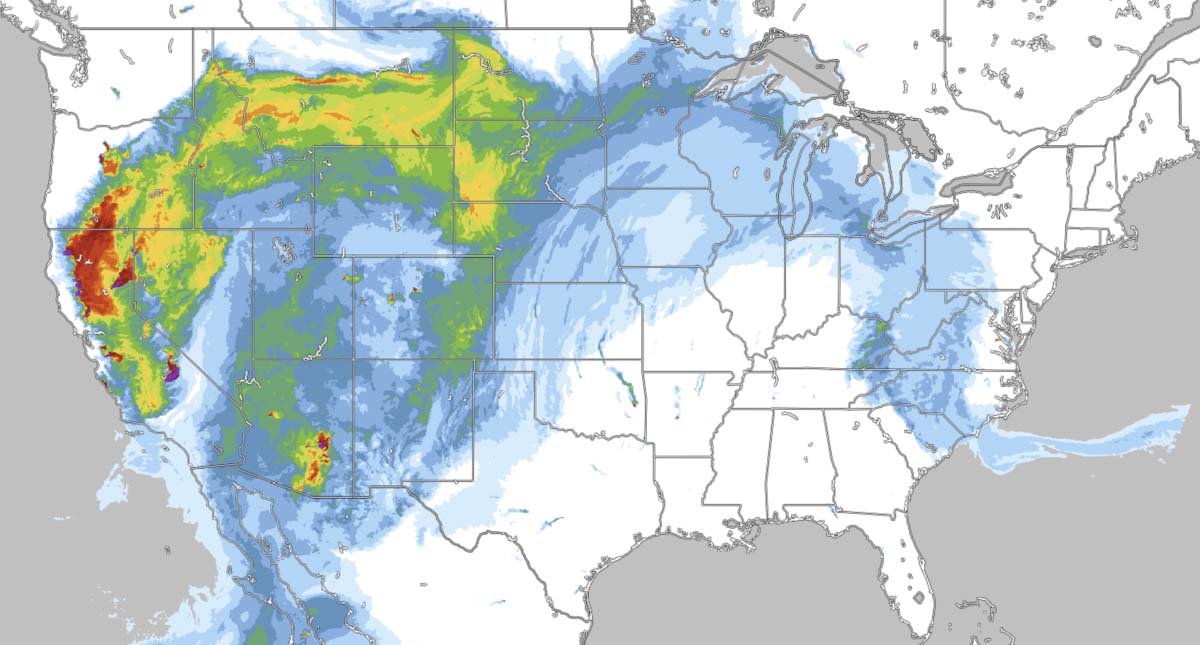

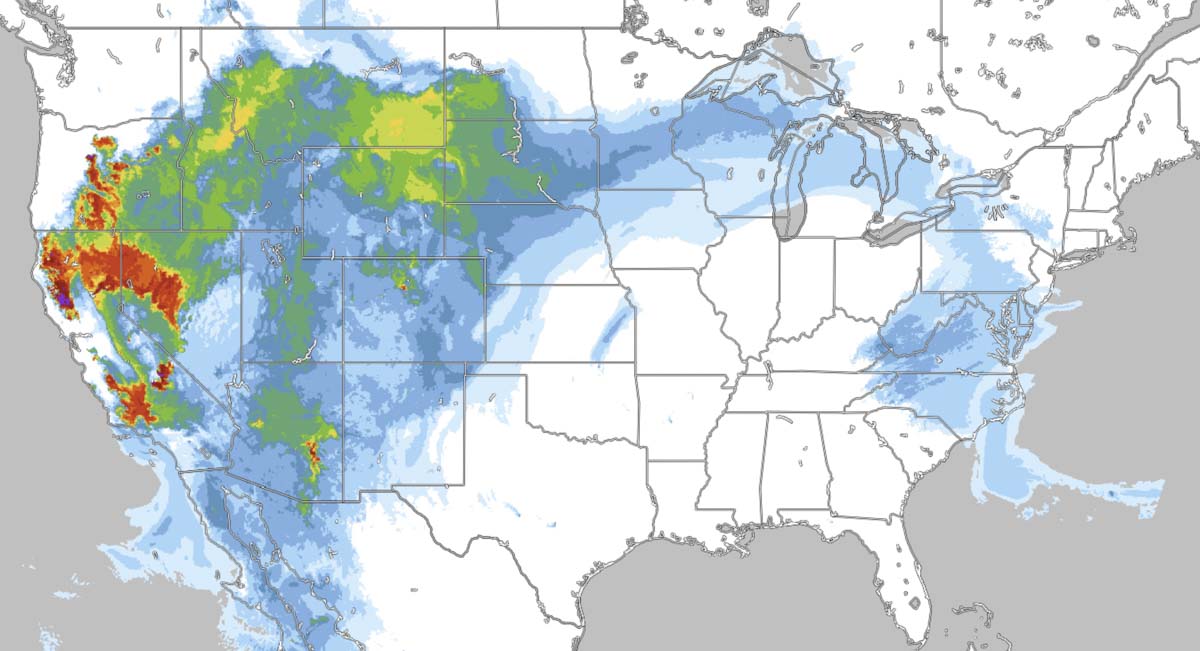

The two maps below distributed by Geographic Area Coordination Centers (GACC) on Twitter attempt to warn the public about the elevated danger of wildfires caused by actual or predicted lightning. I would venture a guess that the general public would have great difficulty figuring out what part of the country they represent based solely on the images. There are no state boundaries that can be easily identified and no cities or highways to make the guessing game easier. The polygons within the maps (which are not counties on the RMACC map) do not convey any worthwhile information to the casual Twitter user, only adding to the confusion.

Wet/dry thunderstorms in E/Co today; lightning activity in the RMA for the past 24 hours showed 10,714 strikes. Strikes blanketed CO, S/WY & E/KS. Western SD saw strikes across the western part of the state w/some in central SD. pic.twitter.com/6pqenkCKFn

— RMACC (@RMACCinfo) August 30, 2020

Fire Potential Impact Map for Sunday-Tuesday, 8/30/2020 – 9/1/2020.#gbcc #greatbasincoordinationcenter @GreatBasinCC

Daily Outlook video briefing located at: https://t.co/PNWyKaeHDh pic.twitter.com/lowcYgoz3V

— GBCC News and Notes (@GreatBasinCC) August 30, 2020

I am a harsher critic of maps than most, having spent many fire assignments as Situation Unit Leader and Planning Section Chief, producing maps for firefighters and the public. Map making continues at Wildfire Today, producing graphics to illustrate the location of fires.

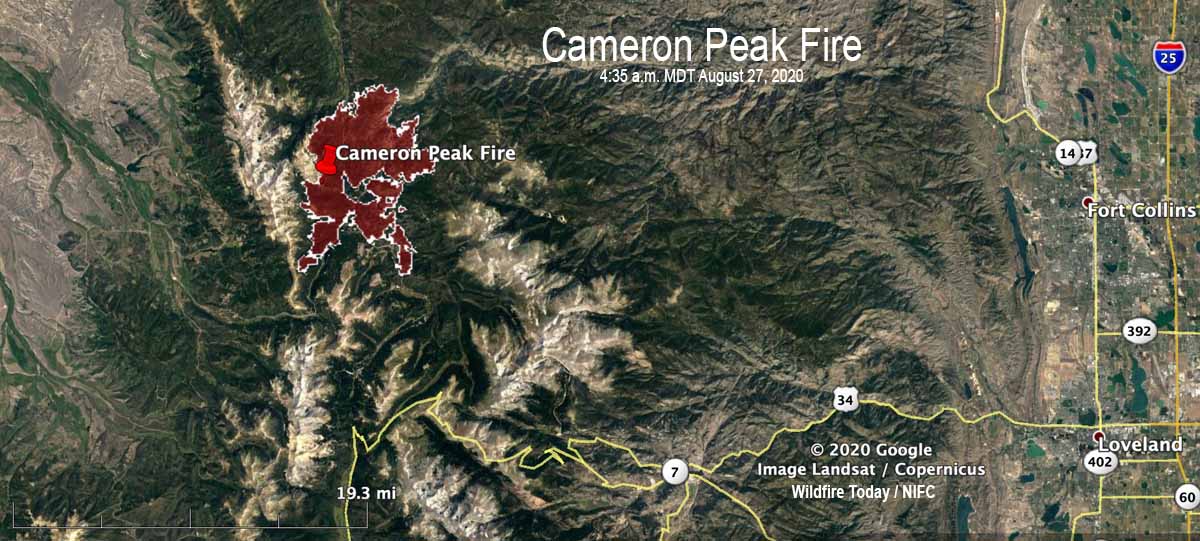

When the public sees smoke or they hear about new fires, many of them have one overriding question. Where is the fire? Unless they have property in the area, the typical person does not need to know that the fire is 300 feet west of Forest Service Road 24D3. They also don’t care about division breaks or helicopter dip sites. They need a map so they can figure out, in many cases, where the fire is in relation to them or their community. A map that is zoomed in so tight that the geographical context of the fire can’t be seen, is often not helpful to the public. A person can get oriented more easily if they can see highways and one or more cities/towns/communities. But if the incident is in a very remote area, that can be difficult.

I visited InciWeb today and found some good, bad, and ugly examples. All of the images below were large files that needed to be reduced in size to show here; the original images have more detail.

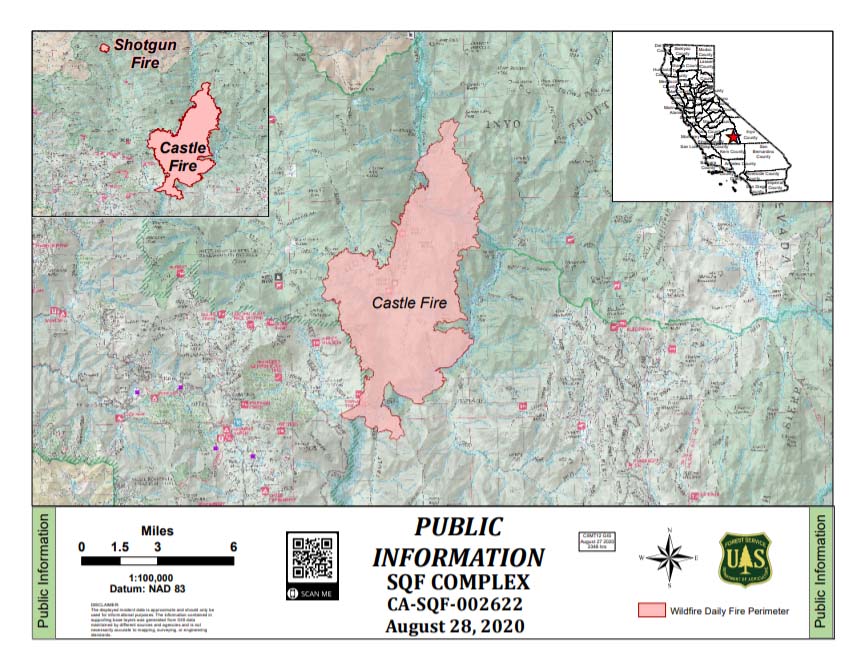

The map below of the Castle and Shotgun Fires on the Sequoia National Forest appears to be based on the standard Forest Service recreation map that forest visitors can purchase — on paper. It is shaded, which may represent vegetation and/or topography and also includes virtually every Forest Service site or feature that exists, including dirt roads. The result is clutter that unless a person has a high-resolution copy of the image and plenty of time, it is difficult or impossible to find paved roads, highways, or communities that could help a person to get oriented. At least it has a vicinity map at upper-right so we know it is in central California.

The base map used for fire public information maps should not be topographical lines or the standard F.S. recreation map.

The map of the Griffin Fire below is better. It is zoomed out providing geographical context, and is not cluttered. But much of the very small text is difficult or impossible to read.

The map below shows five widely separated fires in Arizona so it has quite a bit of context. It shows many, many dirt roads, but that helps to show the location of the three fires on the east side. I don’t know that the shaded relief background adds value, but it has a vicinity map, which is a plus. Overall, a very good map.

The map of the P515 and Lionshead Fires in Oregon deserves praise for its simplicity and lack of clutter. The colors showing ownership are all very different from each other, making it simple to compare them to the helpful legend. It is effective and easy to comprehend. The Lionshead Fire is so close to the edge it makes me wonder what is just off the map to the west. Probably more of the same, but still…

(One of my pet peeves is when six similar shades of brown, for example, represent different features. Not a problem on this map.)

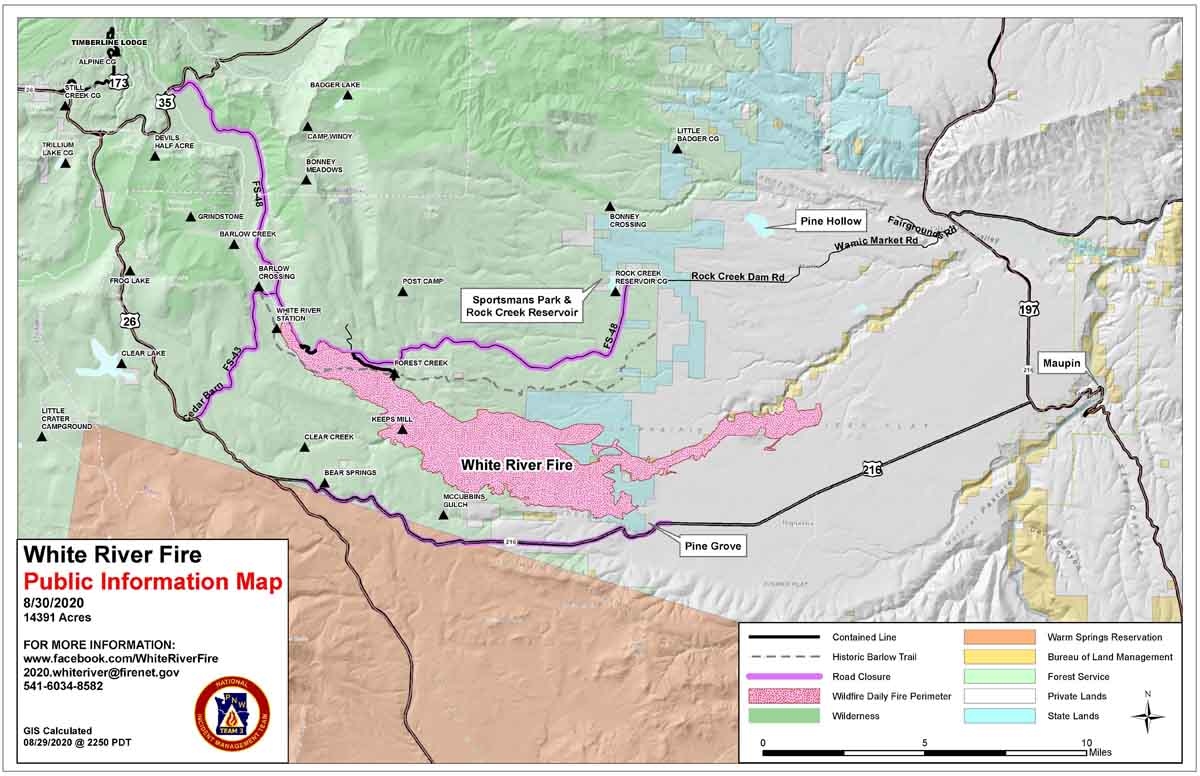

The best map that I ran across during my quick perusal of InciWeb today is the White River Fire on the Mt. Hood National Forest in Oregon. The map maker made sure to include at least one community and several highways. They even went the extra step of adding three labels to features with which the public may be familiar. It is pleasing to the eye, has a useful legend, and the highways near the fire are identified. Even though much of the fire is on Forest Service responsibility land, they resisted the urge to use the FS recreation map as a base map. Great job, White River Fire. (Contact us and we’ll send you a prize, a Wildfire Today cap.)