Above: The Tok River Fire as the helicopter landed. The helicopter is in the brown grassy area near the bottom of the photo.

The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center has released a report they call a “Rapid Lesson Sharing” about a close call that happened in Alaska late in the afternoon on July 14, 2016.

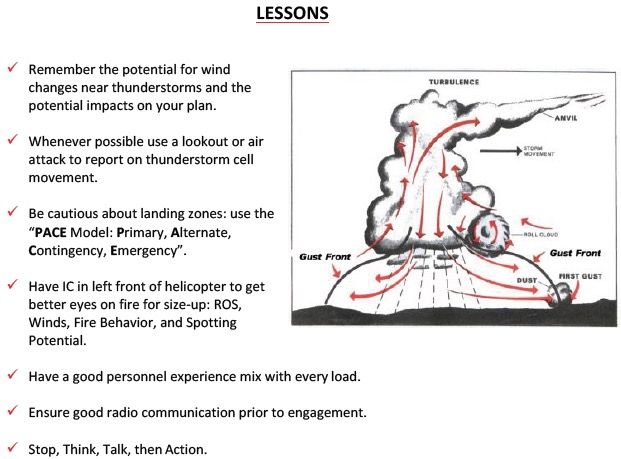

The report does not clearly, unequivocally, and in detail describe how and why the wind changed and affected the direction of spread, but there are two clues. The “Event Type” is “Thunderstorm Influence on IA [initial attack]”. And, the “Lessons” section has tips about attacking a fire when thunderstorms are in the area.

In this incident, a helicopter ferried an Incident Commander and three firefighters to a new fire. As they approached and made several orbits over the new start to size it up they noticed a thunderstorm in the general area. The fire was 10 to 15 acres and burning in black spruce with 50 to 75-foot flames at the head. The pilot and the helicopter manager on board selected a “tussock” (a grassy area) as a landing zone.

Below is an excerpt from the report, which you can read in full here.

****

“….The decision was made to land the helicopter, unload firefighters and equipment, and prepare the helicopter to begin making bucket drops. With the wind blowing out of the southeast, a tussock near the heel of the fire to the north and east was selected as a Landing Zone.

Tussock Believed to be a Good LZ Location

The Helicopter Manager and Pilot both felt that the tussock was a good location because it was close to the heel of the fire and the proximity of water sources. In addition, the IC felt that the tussock was in a good location and of sufficient size that it could be burned-out to create a safety zone in a worst case scenario.

When the bucket was attached, the helicopter left to begin making water drops on the heel of the fire. The IC began walking across the tussock toward the heel to size-up the fire from the ground and make a plan for containment. As he negotiated the uneven ground of the tussock, travel was slow and difficult. The IC had only gone about 200 feet when he began to feel the heat from the fire. He looked up to see the smoke column rotating and moving in the direction of the tussock area where crew had landed.

The winds had shifted approximately 90 degrees. Now the heel of the fire, which moments before had been burning with low intensity, began actively burning— heading toward the IC and his crew.

The helicopter Pilot had just filled his second bucket. He quickly dropped the water when he noticed the wind shift and flew back to the landing zone.

The IC turned around and headed back toward the Landing Zone. He got about half way back when the helicopter returned to the Landing Zone and turned on the siren to alert the fire crew.

Decision Made to Leave Their Gear and Board the Helicopter

The crew disconnected the bucket and began loading gear back on the helicopter. When the crew began packing the bucket, the Pilot told them to leave it and get on the helicopter.

The smoke column was leaning over the tussock and the pilot was concerned that if the column dropped too close on the ground, he would not have enough visibility to lift off.

The fire crew did not believe that they were in imminent danger and that they had plenty of time to load the rest of the gear before they would be affected by the flaming front. However, there was concern that if they lost visibility they would be stuck in the landing zone.

The decision was made to leave the rest of the gear and get in the Helicopter. After taking off, the helicopter made several revolutions around the area hoping to be able to land again and retrieve their gear. The fire continued burning in the direction of the Landing Zone, growing from approximately 16 acres at 1730 to an estimated 100 acres at 1810. The helicopter bucket, a chainsaw, a pump, and a flight helmet were all eventually consumed by the approaching fire…”