Forest Service Chief Randy Moore announced that the nearly four-month suspension on prescribed fires has been lifted after receiving the findings and recommendations provided by a National Review Team.

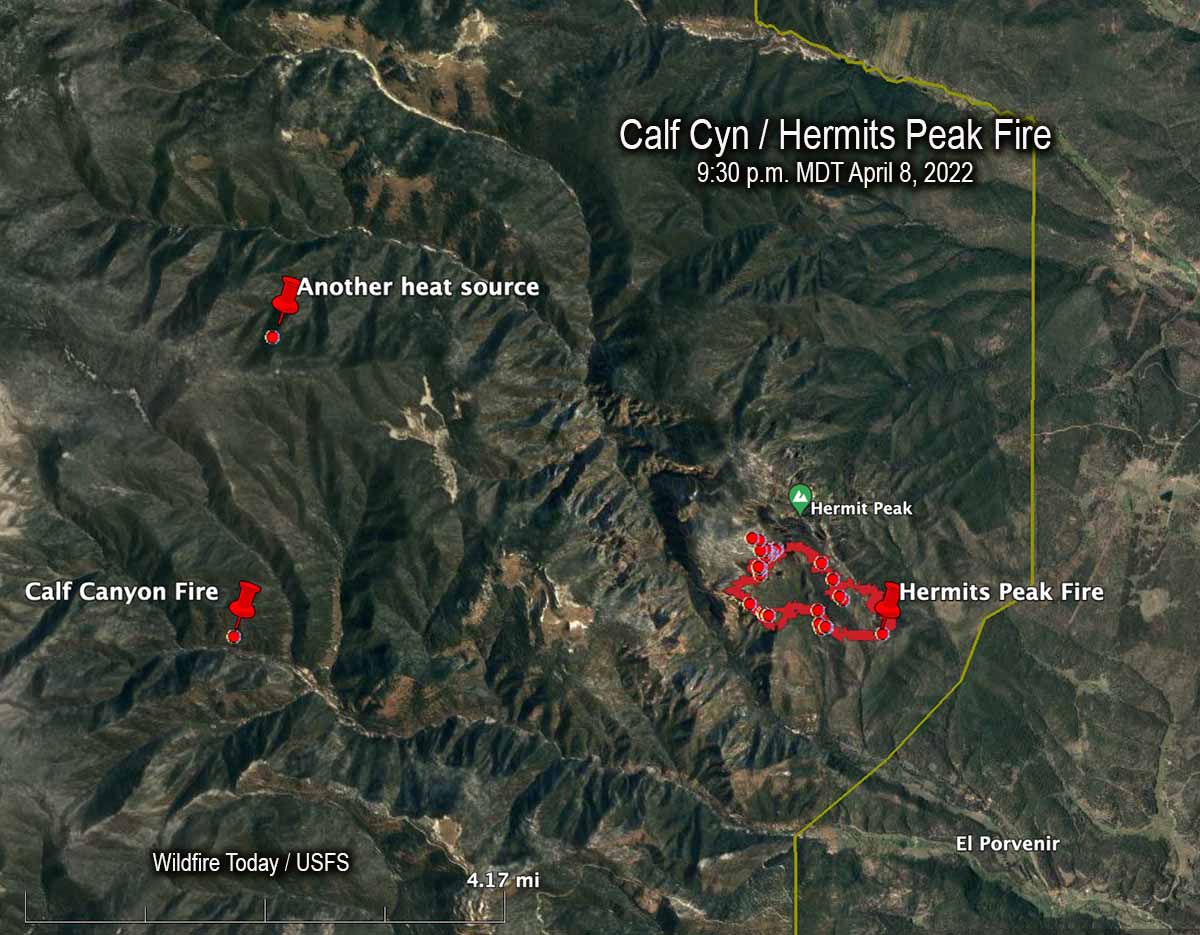

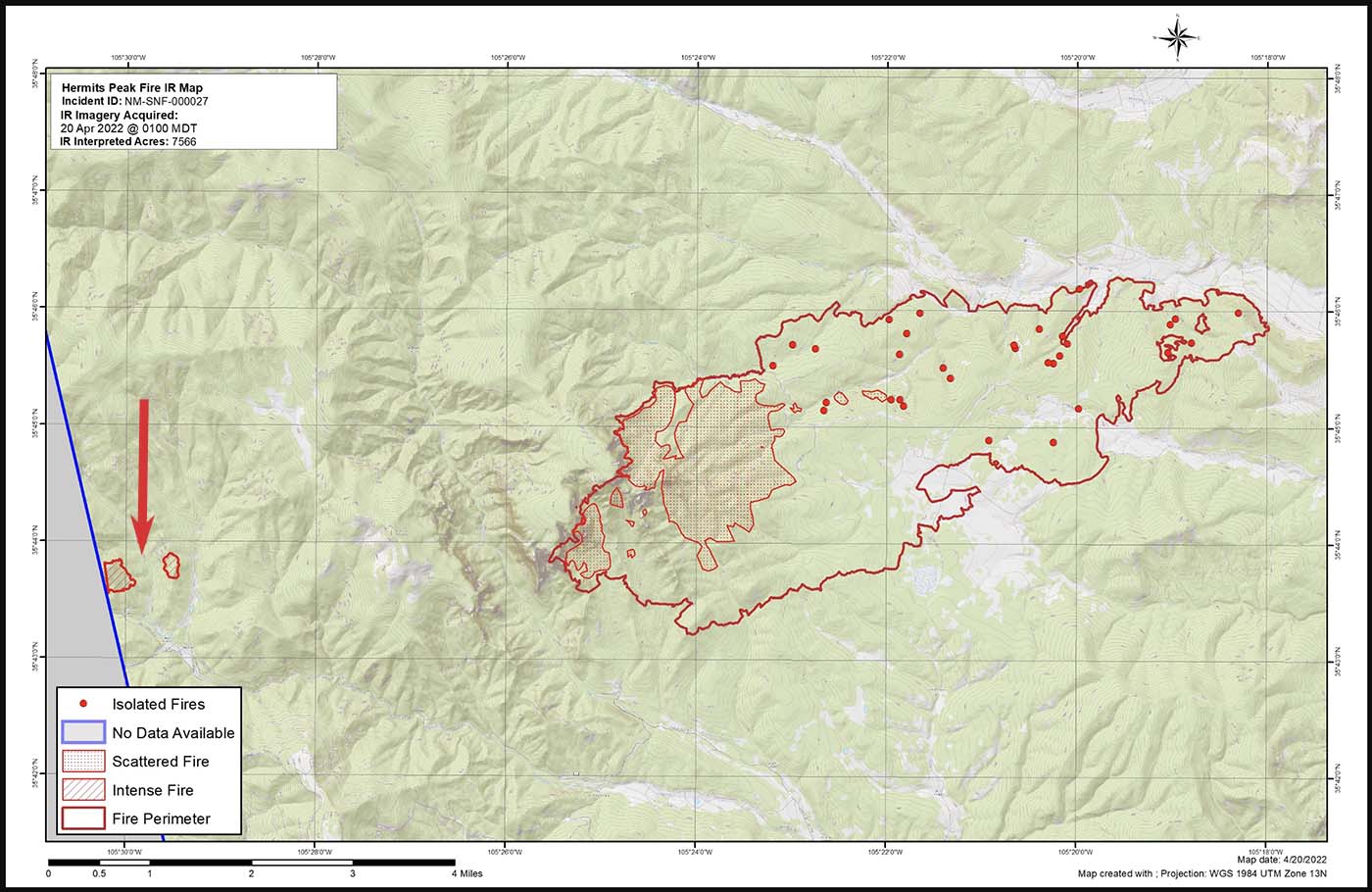

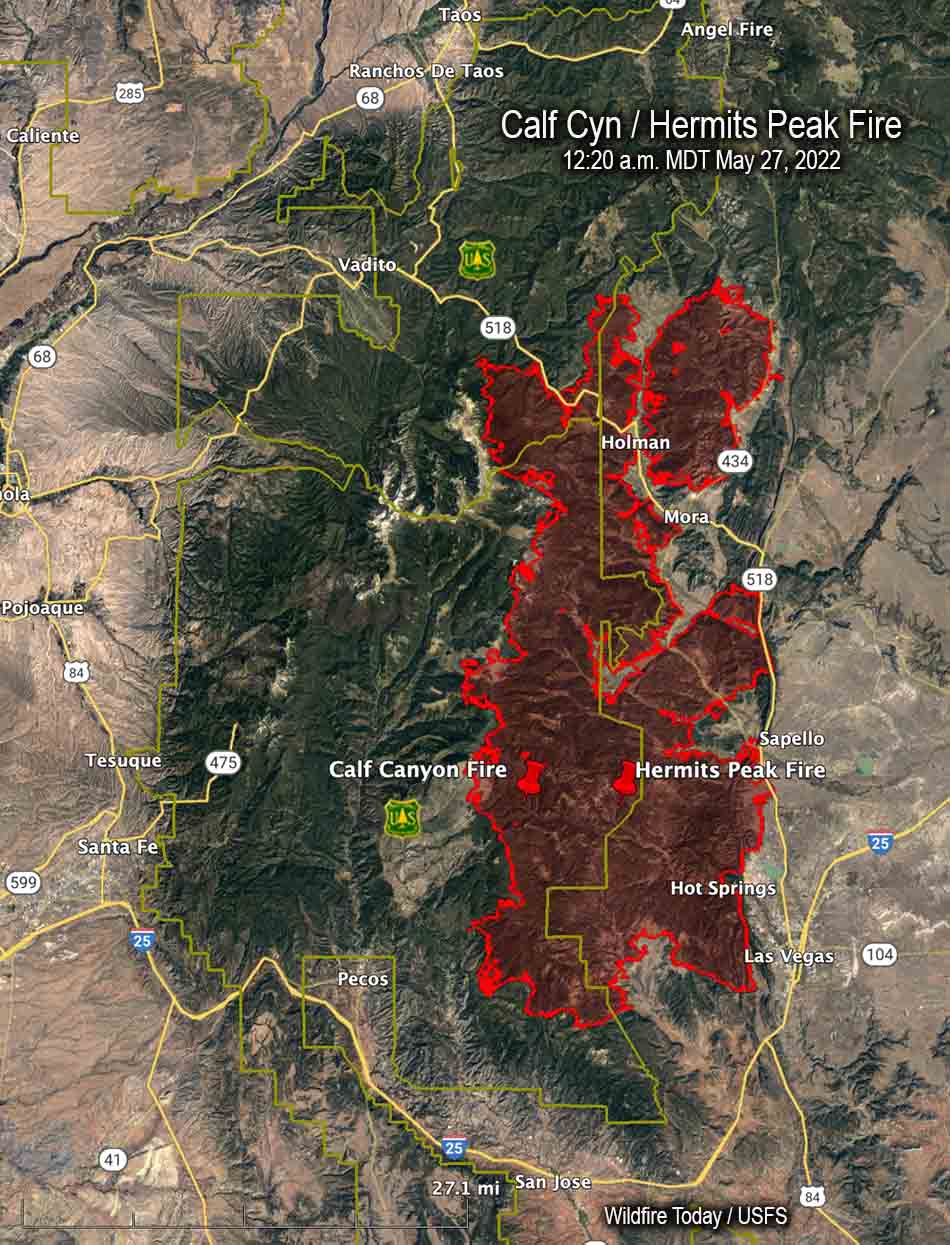

The suspension and review occurred after two prescribed fires on the Santa Fe National Forest in Northern New Mexico escaped in April, merged, and became the Calf Canyon – Hermits Peak wildfire that burned more than 341,000 acres and 903 structures. The area was later hit by flash floods which resulted in more damage. On September 18 the fire will transition from a Type 2 Incident Management Team to a Type 3 Team.

A report released by the Forest Service in June about the two escaped fires concluded the approved prescribed fire plan was followed for most but not all of the parameters. The people on the ground felt they were close to or within the prescription limits but fuel moistures were lower than realized and increased heavy fuel loading after fireline preparation contributed to increasing the risk of fire escape.

The National Review Team that evaluated the agency’s prescribed fire program produced a 107-page report which included seven recommendations. Chief Moore said in a statement, “I have decided to conditionally resume the Forest Service’s prescribed fire program nationwide with the requirement that all seven tactical recommendations identified are followed and implemented immediately by all Forest Service units across the country. These actions will ensure prescribed fire plans are up to date with the most recent science, that key factors and conditions are closely evaluated the day of a prescribed burn, and that decisionmakers are engaged in those burns in real time to determine whether a prescribed burn should be implemented.”

The seven recommendations in the report:

1. Each Forest Service unit will review all prescribed fire plans and associated complexity analyses to ensure they reflect current conditions, prior to implementation. Prescribed fire plans and complexity analyses will be implemented only after receiving an updated approval by a technical reviewer and being certified by the appropriate agency administrator that they accurately reflect current conditions.

2. Ignition authorization briefings will be standardized to ensure consistent communication and collective mutual understanding on key points.

3. Instead of providing a window of authorized time for a planned prescribed fire, agency administrators will authorize ignitions only for the Operational Period (24 hours) for the day of the burn. For prescribed fires requiring multi-day ignitions, agency administrators will authorize ignitions on each day. Agency administrators will document all elements required for ignition authorization.

4. Prior to ignition onsite, the burn boss will document whether all elements within the agency administrator’s authorization are still valid based on site conditions. The burn boss will also assess human factors, including the pressures, fatigue, and experience of the prescribed fire implementers.

5. Nationwide, approving agency administrators will be present on the unit for all high-complexity burns; unit line officers (or a line officer from another unit familiar with the burn unit) will be on unit for 30-40% of moderate complexity burns.

6. After the pause has been lifted, units will not resume their prescribed burning programs until forest supervisors go over the findings and recommendations in this review report with all employees involved in prescribed fire activities. Forest supervisors will certify that this has been done.

7. The Chief will designate a specific Forest Service point of contact at the national level to oversee and report on the implementation of these recommendations and on the progress made in carrying out other recommendations and considerations raised in this review report.

Chief Moore said two additional actions will occur by the end of this year:

- Working with the interagency fire and research community and partners they will establish a Western Prescribed Fire Training curriculum to expand on the successes of the National Interagency Prescribed Fire Training Center headquartered in Tallahassee, Florida.

- The Forest Service will identify a strategy, in collaboration with partners, for having crews that can be dedicated to hazardous fuels work and mobilized across the country to support the highest priority hazardous fuels reduction work.