The National Interagency Fire Center published a photo of a chain saw operator on their Facebook page. After about 28 hours it had collected over two dozen comments, with many of them being critical of what they saw in the photo.

Tag: safety

Colorado to evaluate devices for tracking firefighters

Wildfire Today has unabashedly advocated the the use of devices that would make wildfire supervisors aware in near-real-time the location of their firefighting resources. Our thinking is, if that and the location of the fire were known on the Yarnell Hill and Esperanza Fires the lives of 24 firefighters might have been saved. (See tag for “Holy Grail of Wildland Firefighting Safety”).

In 2014 the governor of Colorado signed legislation creating the Center of Excellence for Advanced Technology Aerial Firefighting (CoE), whose mission statement says they will:

…research, test, and evaluate existing and new technologies that support sustainable, effective, and efficient aerial firefighting techniques.

Apparently the organization interprets that mission very broadly since they have started a study to evaluate the effectiveness and practicality of small GPS-enabled devices that can communicate with firefighters on the ground and keep track of their location via satellites.

In 2012 the U.S. Forest Service bought 6,000 devices like this. We have not heard much about how that acquisition turned out.

Below is information about the new Colorado project provided by the (CoE).

****

“In the interest of improving communications for, and safety of, wildland firefighters, the Center of Excellence (CoE) is evaluating the use of satellite-based messenger devices by Division of Fire Prevention and Control (DFPC) firefighters and cooperators. These devices can enable firefighters to send messages and they also track the location of personnel without using cellular or conventional radio networks. To date, the primary users of these devices have been the civilian outdoor community; however, military and civil government agencies have begun experimenting with integrating these devices into their operations. Early results show that satellite messengers can be effective at supplementing existing radio and cellular communication networks.

Device Overview

Two types of devices are being evaluated by the CoE. The first is the lower-cost SPOT Gen3, which can send one-way messages over the Globalstar satellite network. Since SPOT Gen3’s have sending capability only, it is not possible to obtain delivery confirmations for successful messages. To increase the probability that messages are successfully delivered, the SPOT sends multiple copies of the same message.

The SPOT Gen3 device can send the following types of messages:

- An SOS message that triggers a search and rescue response

- A “Help” message that delivers a preset distress message and the device’s location to designated contacts

- A customized message with preset content that is input into the SPOT website prior to a trip

- A message stating that the device user is “OK,” which is sent to designated contacts

- Tracking points sent at preset intervals that show the device’s current location

The second device that the CoE is evaluating is the DeLorme inReach. Two models of the inReach are being evaluated—the basic model and a premium model that includes GPS mapping and navigation. The inReach can send two-way messages over the Iridium satellite network, which provides delivery confirmations for successful messages. In addition, text messages can be sent to firefighters in the field.

The DeLorme InReach device can send the following types of messages:

- An SOS message that triggers a search and rescue response, though in this case the search and rescue coordination center can customize the response based on a text message conversation with the device user

- Preset or customized messages sent via a virtual keyboard, or the inReach device can pair with Apple or Android smartphones and allow users to control all features of the device, including text input through their smartphones

- Tracking information at preset intervals

The SPOT Gen3 device retails for $149.99, the DeLorme inReach base model (inReach SE) for $299.99, and the premium model (inReach Explorer) for $379.99. Satellite service subscriptions comprise a substantial portion of the cost of operating these devices, with cost primarily governed by how frequently tracking points can be sent by the device. Service for the SPOT device must be bought on an annual basis, while service for the DeLorme devices can be purchased on either an annual or a month-to-month basis. If the DeLorme devices are used for 8 months or less each year, the month-to-month plan will be the most cost-effective option.

Summary of Device and Service Costs:

| SPOT (annual) | DeLorme Contract (annual) | DeLorme Month-to-Month (plus $24.95 annual fee) | |

| Device Cost | $149.99 | $299.99/$379.99 | $299.99/$379.99 |

| Base Option |

|

|

|

| Mid-Range Option |

|

|

|

| Premium Option |

|

|

|

The following chart represents the cost of buying and operating a device for two years, assuming that the DeLorme devices are on the month-to-month plan and are used for 6 months each year:

An enterprise plan is also available for the DeLorme devices. This plan charges for each byte of data used by the device rather than by the various texting and tracking features. As a result, a direct comparison to the consumer plans is difficult, but superior value may be found if usage is carefully monitored. Real-world testing of this plan is being conducted by the CoE to gain insight into its value.

Both the SPOT and DeLorme devices may be used by DFPC wildland fire personnel during fire assignments and remote project work. Using either device, personnel in need of emergency medical assistance or personnel lost in the wildland will be able to summon search and rescue assistance. Additionally, personnel will have the ability to send messages with other content to supervisors or incident commanders, though this functionality is limited with the SPOT device. Finally, the location of personnel can be tracked in near real-time using either the companion websites for the devices or using the Colorado Wildfire Information Management System (CO-WIMS).”

Legislation introduced to acquire system to track location of state firefighters in Washington

Photo above: 19 white hearses brought the Granite Mountain Hotshots back to Prescott, Arizona, July 7, 2013. They were killed after being overrun by the Yarnell Hill Fire. Photo by Bill Gabbert.

A bill introduced in the Washington state legislature would provide for state employed firefighters a system that would track their location. Knowing where firefighters are while working on a rapidly spreading fire is crucial to ensuring their safety, and is half of what we have called Holy Grail of Firefighter Safety. The other half is knowing the real time location of the fire relative to the personnel. If a Division Supervisor, Operations Section Chief, or Safety Officer is monitoring this information they could potentially warn firefighters that their present position is in danger when the fire begins to spread in their direction. A system like this might have saved 24 lives on the 2013 Yarnell Hill and 2006 Esperanza Fires. In both cases the firefighters and their supervisors did not have a clear understanding of where the fire and the firefighters were.

In a January 18 article about how to reduce the number of fatalities on wildland fires, we wrote:

When you think about it, it’s crazy that we sometimes send firefighters into a dangerous environment without knowing these two very basic things.

Below is a section from House Bill 2924 as introduced in the Washington State Legislature on January 27, 2016, sponsored by six lawmakers:

…Require all fire suppression equipment and personnel in its employ or direction to be outfitted with an electronic monitoring device that utilizes global positioning system technology to protect the safety of wildland firefighters…

The Seattle Times wrote about the proposed legislation. Here is an excerpt:

…DNR has done some early research on GPS, according to Bob Johnson, the agency’s wildfire-division manager. Setting up a system could cost $1.5 million, Johnson told lawmakers.

“Improving safety for our firefighters is paramount and we’d view this technology … as a viable supplement to existing safety measures,” wrote Mary Verner, DNR’s deputy supervisor for resource protection. “Though, it, like many technologies, does have its limitations.”

Challenges, benefits

GPS locaters are used by various departments and agencies around the country, according to Triplett.

But there aren’t yet national standards for GPS systems, so when firefighters come from different agencies or another state to fight large blazes, they may not have equipment that works together, according to Triplett.

Steve Pollock, chief regional fire coordinator for the Texas A&M Fire Service, said it took about three years to develop that agency’s GPS system. When it goes live in July, it will be able to track more than 200 bulldozers, fire engines and coordinating vehicles, he said…

There needs to be leadership, nationally, to develop standards for firefighter tracking systems so that the devices used by different agencies are compatible and interoperable. This should be the duty of the National Wildfire Coordinating Group, National Association of State Foresters, U.S. Forest Service, National Park Service, and Bureau of Land Management.

If individual state and local organizations spend millions on stand-alone systems that can’t be used outside their jurisdictions it will be FUBAR. Leadership is needed. Today.

Adding to the list of common denominators of tragedy fires

More common denominators of tragedy fires.

(Photo: Happy Camp Complex, 2014, by Kari Greer.)

About forty years ago Carl Wilson, one of the early wildland fire researchers, developed his list of four “Common Denominators of Fire Behavior on Tragedy Fires”, that is, fatal and near-fatal fires.

- Relatively small fires or deceptively quiet areas of large fires.

- In relatively light fuels, such as grass, herbs, and light brush.

- When there is an unexpected shift in wind direction or wind speed.

- When fire responds to topographic conditions and runs uphill. Alignment of topography and wind during the burning period should always be considered a trigger point to re-evaluate strategy and tactics.

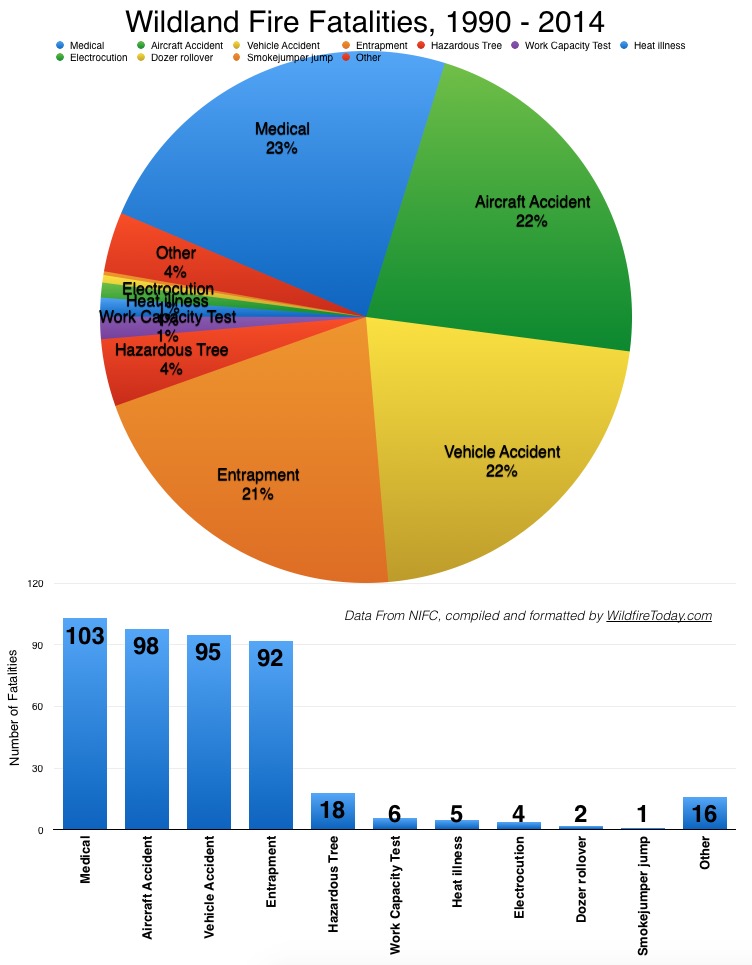

Our study of the 440 fatalities from 1990 through 2014 shows that entrapments are the fourth leading cause of deaths on wildland fires. The top four categories which account for 88 percent are, in descending order, medical issues, aircraft accidents, vehicle accidents, and entrapments. The numbers for those four are remarkably similar, ranging from 23 to 21 percent of the total. Entrapments were at 21 percent.

But as Matt Holmstrom, Superintendent of the Lewis and Clark Interagency Hotshot Crew recently wrote for an article in Wildfire Magazine, Mr. Wilson’s common denominators only address fire behavior.

Mr. Holmstrom explored eight human factors that he believes merit consideration. I’m generously paraphrasing, but here are the areas he mentioned:

- Number of years of experience.

- Time of day (especially between 2:48 p.m. and 4:42 p.m.)

- Poorly defined leadership or organization.

- Transition from Initial Attack to Extended Attack.

- Earlier close calls or near misses on the same fire.

- Personality conflicts.

- Using an escape route that is inadequate.

- Communication failures.

He goes into much detail for each item and cites numerous fires which he said were examples. It is a thought-provoking article. Check it out.

UPDATE January 29, 2016. Larry Sutton authored an article in a 2011 issue of Fire Management Today (pages 13-17) that also explored the Common Denominators of Human Behavior on Tragedy Fires. At the time Mr. Sutton was the fire operations risk management officer for the U.S. Forest Service at the National Interagency Fire Center in Boise, Idaho.

Drip torch carried on firefighter’s back leaks fuel and ignites, causing serious burns

Last summer a firefighter received severe burns to his back, both legs, and left arm after a drip torch attached to the pack on his back leaked fuel which ignited. The accident occurred September 9, 2015 on the Perdida Fire managed by the Bureau of Land Management northwest of Taos, New Mexico. The firefighter was one of seven igniters assigned to the fire which had a total of nine personnel.

The individual who was injured had been igniting with a drip torch while he carried an extra one attached to the pack on his back. The torch leaked fuel which caught fire.

From the recently released report about the incident:

…Igniter #1 saw that the victim’s line gear and back of his legs were on fire so he tried to put the fire out with dirt and by patting at the flame with his gloved hand. Igniter #1 told the victim to get on the ground and they both fell together. The victim got back up and ran while trying to get his glove off and then his pack, successfully. The victim then stumbled but regained his footing briefly before falling back to the ground. At this point, Igniters #1 and #3 converged and patted out the fire on the victim’s pants…<

The photos below are from the report.

One of the issues pointed out in the report is a significant delay in requesting a medevac. About 40 minutes elapsed before medevac was requested, and that was for a ground ambulance even though the victim apparently had second and third degree burns. That request was quickly upgraded to transport by helicopter. The report concluded that according to the burn injury protocol a medevac should have been initiated upon the determination of second and third degree burns and the remoteness of the incident.

The medevac pilot was unable to communicate with the personnel on the ground because he could not program the frequency into the helicopter’s radio.

The lat/long was called in to dispatch from the incident scene 23 minutes after the helicopter was requested (about an hour after the accident occurred), and four minutes before it landed at the extrication point.

The report recommended that firefighters should avoid carrying extra drip torches on their packs during ignition operations.

We did not see anything in the report about how fire resistant clothing that has not been washed for an extended period of time may, or may not, cause the clothing to lose some of its resistance to fire. But it did say “PPE [personal protection equipment] should be kept clean and inspected often for damage and fuel contamination”.

Entrapments is the fourth leading cause of wildland firefighter fatalities

For the last several days we have been writing about fatalities on wildland fires — the annual numbers and trends going back to 1910 and some thoughts about how to reduce the number of entrapments (also known as burnovers). Often when we think about these accidents, what automatically comes to mind are the entrapments. When multiple firefighters are killed at the same time it can be etched into our memory banks to a greater extent than when one person is killed in a vehicle rollover or is hit by a falling tree. Much of the nation mourned when 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshots were overrun and killed by the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona in 2013. A fatal heart attack on a fire does not receive nearly as much attention.

For the last several days we have been writing about fatalities on wildland fires — the annual numbers and trends going back to 1910 and some thoughts about how to reduce the number of entrapments (also known as burnovers). Often when we think about these accidents, what automatically comes to mind are the entrapments. When multiple firefighters are killed at the same time it can be etched into our memory banks to a greater extent than when one person is killed in a vehicle rollover or is hit by a falling tree. Much of the nation mourned when 19 members of the Granite Mountain Hotshots were overrun and killed by the Yarnell Hill Fire in Arizona in 2013. A fatal heart attack on a fire does not receive nearly as much attention.

When we discuss ways to decrease deaths on fires, for some of us our first thoughts are how to prevent entrapments, myself included. One reason is that it can seem they are preventable. Someone made a decision to be in a certain location at a specific time, and it’s easy to think that if only a different decision had been made those people would still be alive. Of course it is not that simple. Perfect 20/20 hindsight is tempting for the Monday Morning Incident Commander. Who knows — if they had been there with access to the same information they may have made the same series of decisions.

An analysis of the data provided by NIFC for the 440 fatalities from 1990 through 2014 shows that entrapments are the fourth leading cause of fatalities. The top four categories which account for 88 percent are, in decreasing order, medical issues, aircraft accidents, vehicle accidents, and entrapments. The numbers for those four are remarkably similar, ranging from 23 to 21 percent of the total. Number five is hazardous trees at 4 percent followed by the Work Capacity Test, heat illness, and electrocution, all at around 1 percent. A bunch of miscellaneous causes adds up to 4 percent.

NIFC’s data used to separate air tanker crashes from accidents involving other types of aircraft such as lead planes and helicopters. But in recent years they began lumping them all into an “aircraft accident” category, so it is no longer possible to study them separately. This is unfortunate, since the missions are completely different and involve very dissimilar personnel, conflating firefighters who are passengers in the same category as air tankers having one- to seven-person crews — from Single Engine Air Tankers to military MAFFS air tankers.

The bottom line, at least for this quick look at the numbers, is that in addition to trying to mitigate the number of entrapments, we should be spending at least as much time and effort to reduce the numbers of wildland firefighters who die from medical issues and accidents in vehicles and aircraft.