The map showing the distribution of smoke from wildfires has a very interesting pattern today.

News and opinion about wildland fire

President Obama today signed an Executive Order on Wildland-Urban Interface Federal Risk Mitigation, intended to mitigate wildfire risks to Federal buildings located in the wildland-urban interface (WUI), reduce risks to people, and help minimize property loss to wildfire.

For new buildings and alterations to existing buildings greater than 5,000 square feet on Federal land within the WUI at moderate or greater risk to wildfire, the Executive Order directs Federal agencies to apply wildfire-resistant design provisions delineated in the 2015 edition of the International Wildland-Urban Interface Code promulgated by the International Code Council, or an equivalent code. These codes, which encompass the current understanding of wildfire hazard potential, will help increase safety and protect the lives of people who live or work in these buildings.

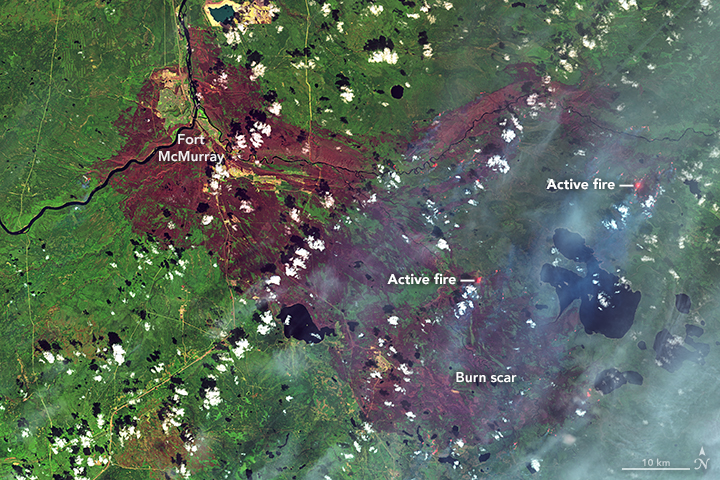

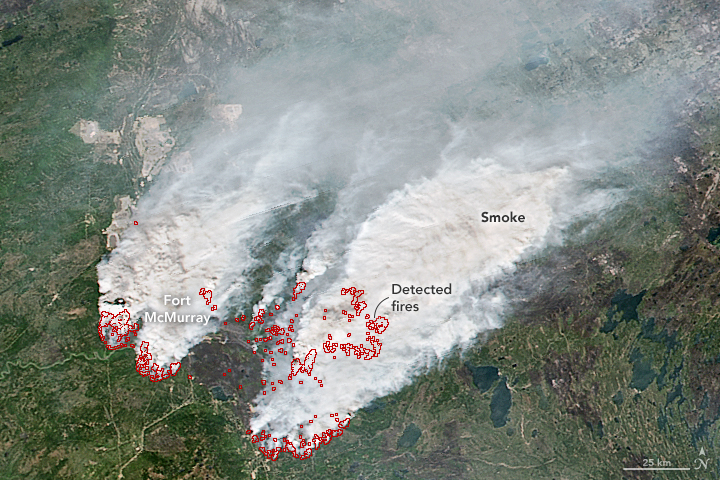

NASA provided these images of the wildfire at Fort McMurray (Horse River Fire) in Alberta as seen from the Landsat 8 satellite. The one above was acquired on May 12, a day when there was little activity on the fire. In contrast to that, check out the image below taken on May 16 when conditions were very different.

Our most recent comprehensive article about the Fort McMurray Fire is HERE.

After reading the Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) about the Rhabdomyolysis (Rhabdo) injury that occurred May 2 in South Dakota on the first day of the fire season after running for more than nine miles before doing uphill sprints, I started thinking about, not so much WHAT happened, but how to prevent similar serious injuries.

After reading the Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) about the Rhabdomyolysis (Rhabdo) injury that occurred May 2 in South Dakota on the first day of the fire season after running for more than nine miles before doing uphill sprints, I started thinking about, not so much WHAT happened, but how to prevent similar serious injuries.

A couple of weeks before the Rhabdo case, on April 19 a wildland firefighter in the Northwest suffered a heat stroke while running on day 2 of their season. The employee was unconscious for several hours and spent four days in the hospital.

Both of these exercise-induced conditions can be life-threatening; 33 percent percent of patients diagnosed with Rhabdo develop a quick onset of kidney failure, and 8% of all cases are fatal.

Heat stroke can also kill, according to Medscape:

When therapy is delayed, the mortality rate may be as high as 80%; however, with early diagnosis and immediate cooling, the mortality rate can be reduced to 10%.

These two very serious incidents in a two week period that occurred at the beginning of the fire season should be a wakeup call for agencies employing wildland firefighters.

I am not a medical or exercise specialist, but neither were any of the four members of the South Dakota Rhabdo FLA team. It was comprised of a District Fire Management Officer, a Natural Resources Specialist, an Assistant Superintendent on a Hotshot crew, and an Assistant Fire Engine Operator.

A person might expect that for an exercise-induced injury that is fatal in eight percent of the cases, a medical expert and an exercise physiologist would be members of the team. The FLA concentrated on recognizing symptoms of Rhabdo, which is good. Firefighters need to be be informed, again, about what to look for. But the necessity of treating the symptoms could be avoided if the condition was prevented in the first place.

Prevention was not addressed in the document, except to mention availability of water. Dehydration isn’t the leading cause of Rhabdo, which is caused by exertion, but it can be a contributing factor.

With two life-threatening medical conditions on firefighting crews in a two-week period that occurred during mandatory exercise on day one and two of training, medical and exercise professionals perhaps could have evaluated what caused the injuries, and suggested how to design and implement a physical fitness program that would lessen the chances of killing firefighters on their first or second day on the job. But the LEARNING opportunity of the FLA was squandered.

The wildland fire agencies are not alone in hiring people off the streets and throwing them into a very physically demanding job. The military does this every day, as do high school athletic programs. There is probably a large body of research that has determined how to turn a person into an athlete without putting their lives in danger.

While the three firefighters and the natural resources specialist I’m sure meant well and did the best they could to write the FLA within the limits of their training and experience, the firefighting agencies need to get serious about a professional level exercise training program. After all, they are employing TACTICAL ATHLETES.

This issue is serious enough that the NWCG (since there is no National Wildland Firefighting Agency) should hire an exercise physiologist who can design, implement, and monitor a program for turning people off the street into tactical firefighting athletes.

33% of patients diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis develop a quick onset of kidney failure, and 8% of all cases are fatal.

The Wildland Fire Lessons Learned Center has released a Facilitated Learning Analysis for the Rhabdomyolysis injury that occurred May 2, 2016. It does not specify that it was the case that occurred on the Black Hills National Forest, but many of the facts in the document point to it being the same incident.

The short version of what preceded the injury is that on the morning of the first day of the seasonal firefighters reporting for duty this fire season, the crew was directed to complete an 8.8 mile run which they did in 96 minutes. Approximately 1/2 mile into the run one crewmember dropped out and was evaluated by a squad boss and an EMT. The crewmember and the EMT returned to the base. This was not the person later diagnosed with Rhabdo.

After the 8.8 mile run the crew jogged another 3/4 mile to a location where they ran uphill sprints and a “loop run”. From the report, after the 8.8 mile run:

Upon return to station, the remainder of the crew reconfigured and lined-out in “tool-order” to continue PT. It was noted that during this brief lull in activity, the employee who would eventually be diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis made the comment “It’d be nice to have some water…”, to which another within ear-shot replied “yeah… I know”. The “long, slow run” was followed by three rounds of relatively short uphill sprints interrupted by a “loop-run” within sight of the hot-shot base. This event lasted roughly forty-five minutes.

Although dehydration isn’t the leading cause of Rhabdomyolysis, which is a condition caused by exertion, it can be a contributing factor.

The crewmember did not inform the supervisors that he was having discomfort and cramping, but about an hour after the work day ended he drove himself 41 miles to seek treatment at a medical facility.

At 0745 on the [next] morning of May 3rd, the hotshot superintendent was notified by the injured employee’s family that he was in the hospital with dehydration and were awaiting additional test results. He was subsequently diagnosed with Rhabdomyolysis.

The FLA points out, and this should not be news to wildland firefighters, that Rhabdo and compartment syndrome are extremely rare and difficult for a physician to diagnose. Therefore it is imperative that wildland firefighters familiarize themselves with what can cause the condition and how to recognize the symptoms.

Not all past cases of rhabdo in wildland firefighters were correctly diagnosed during initial care. Heat illness and dehydration share common signs/symptoms and can lead to a missed diagnosis for rhabdo. In addition, rhabdomyolysis is a very rare occurrence in the general population. Many physicians will go their entire careers without seeing a single case of rhabdomyolysis. Since early detection and treatment can greatly reduce the severity and recovery time, it is important that medical providers understand and test for rhabdo.

If you are a wildland firefighter, and especially if you are a supervisor, read the entire report, make copies of the Handout for Medical Providers, and if someone exhibits the symptoms and needs treatment, accompany them to the medical facility and diplomatically talk to the physician about the possibility of Rhabdo while giving them a copy of the Handout.

In another injury involving early fire season physical training, on April 19 a wildland firefighter suffered a heat stroke on day 2 of their season. The employee was unconscious for several hours and spent four days in the hospital.

Above: the Brush! Fire Department in Brush, Colorado. Photo by Bill Gabbert.

I have driven through the town of Brush, Colorado several times and each time I thought about the name of the fire department. I casually looked along Highway 71 as I passed through hoping the FD would be on the main north-south road, but didn’t see it.

A couple of weeks ago as I drove through the town on the way to Colorado Springs I decided to hunt down the fire department. It didn’t take long to spot the Brush! Volunteer Fire Department on the west side of town on Edison Street/Highway 34. And I finally got the photo I wanted. After leaving it occurred to me that I should have knocked on the door and asked about the exclamation point — “Brush!”.

I wonder how many other cities are named after a type of vegetation, and thus have a (vegetation) Fire Department like Brush? There’s Forest, Mississippi and the Forest Fire Department. Anyone know of others?