The couple who ignited the huge 2020 El Dorado Fire in San Bernardino County, California by exploding a pyrotechnic device during a “gender-reveal party” was sentenced Friday after reaching a plea deal with prosecutors, according to a report by the Los Angeles Times.

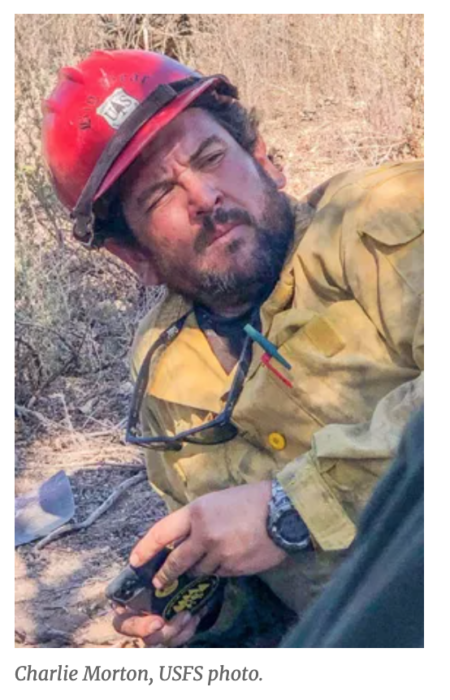

The couple accidentally started the 22,000-acre fire on a scorching hot day in a park in southern California with a device that was supposed to blow either blue or pink smoke. The fire killed USFS firefighter Charlie Morton, a squad boss with the Big Bear Hotshots, injured two other firefighters and 13 civilians, destroyed five homes, and forced hundreds of people to evacuate ahead of the fire.

The San Bernardino County district attorney’s office said Refugio Manuel Jimenez Jr. was sentenced to a year in county jail and two years of felony probation, plus community service — after he pleaded guilty to felony involuntary manslaughter (in Morton’s death) plus two felony counts of recklessly causing fire to an inhabited structure.

USA Today reported that besides jail time, Jimenez will owe 200 hours of community service and will also serve two years of felony probation.

“Resolving the case was never going to be a win,” San Bernardino County district attorney Jason Anderson said. “The Defendants’ reckless conduct had tremendous impact on land, properties, emergency response resources, and the displacement of entire communities — and resulted in the tragic death of Forest Service Wildland Firefighter Charles Morton.”

Angelina Jimenez pleaded guilty to three misdemeanor counts of recklessly causing a fire to another’s property; she was sentenced to a year’s probation and community service. The Jimenezes were ordered to pay victim restitution of $1,789,972.

Charlie Morton hired on with the San Bernardino National Forest in 2007 and worked on both the Front Country and Mountaintop Ranger Districts, for the Mill Creek Interagency Hotshots, Engine 31, Engine 19, and the Big Bear Interagency Hotshots. “Charlie is survived by his wife and daughter, his parents, two brothers, cousins, and friends,” wrote his family at that time. “He’s loved and will be missed. May he rest easy in heaven.”

A note from the Chief’s Office at the time said, “The loss of an employee in the line of duty is one of the hardest things we face in our Forest Service family. Our hearts go out to Charlie’s coworkers, friends and loved ones. Charlie was a well-respected firefighter and leader who was always there for his squad and his crew at the toughest times.”

RIP Charlie and all his brothers.

The couple who ignited the huge 2020 El Dorado Fire in San Bernardino County, California by exploding a pyrotechnic device during a “gender-reveal party” was sentenced Friday after reaching a plea deal with prosecutors, according to a report by the Los Angeles Times.

Charlie Morton, Big Bear Hotshots

The couple accidentally started the 22,000-acre fire on a scorching hot day in a park in southern California with a device that was supposed to blow either blue or pink smoke. The fire killed USFS firefighter Charlie Morton, a squad boss with the Big Bear Hotshots,