A firefighter who had been assigned to a wildfire in Colorado in 2020 died today after battling COVID-19 in a hospital for six months.

From information released by Laramie County Fire District 2:

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of Charles “Chuck” Scottini. Chuck passed away peacefully with his family by his side on the morning of April 24th, 2021 after a long six-month battle with COVID-19. Chuck contracted COVID while on a wildland fire assignment in Colorado and was quickly moved to University of Utah hospital where he stayed for 6 long months trying to recover.

Chuck has been a Firefighter with Laramie County Fire District 2 since 1998, where he currently held the position of Assistant Chief. Chuck was our Mr. fix it, our mentor, and was a wealth of knowledge to the Fire service. He will be dearly missed by all. We will release information on a memorial service at a later time.

The Oil City News reported that earlier this week emergency personnel in Laramie and Cheyenne had honored Assistant Chief Scottini as he was transported from Utah to hospice care in Cheyenne.

Laramie County Fire District 2 was established in 1945 and protects about 1,100 square miles north of Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Our sincere condolences go out to the family, friends, and coworkers of Assistant Chief Scottini.

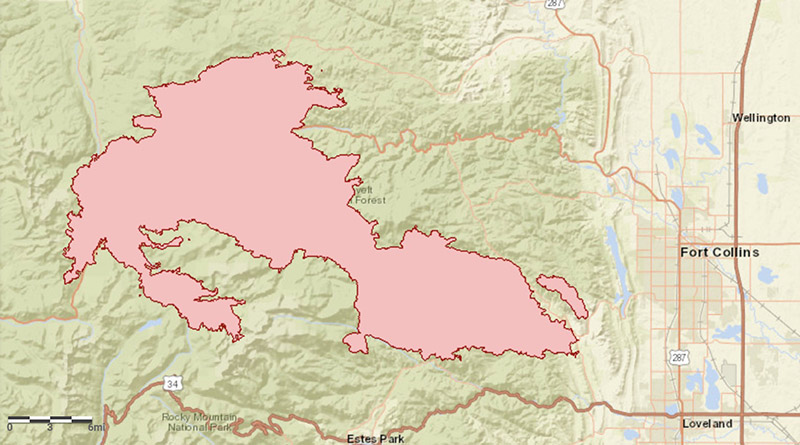

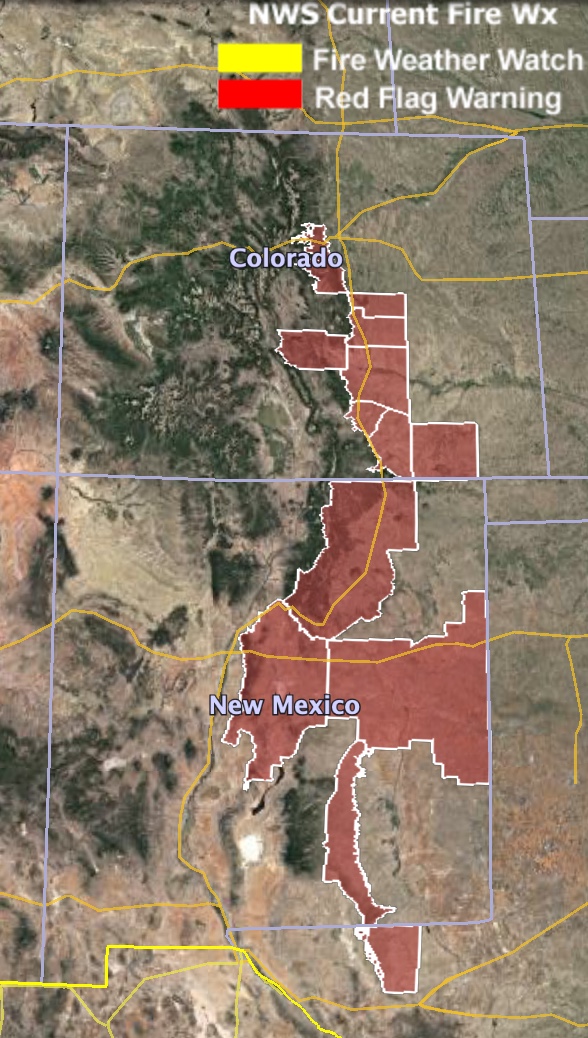

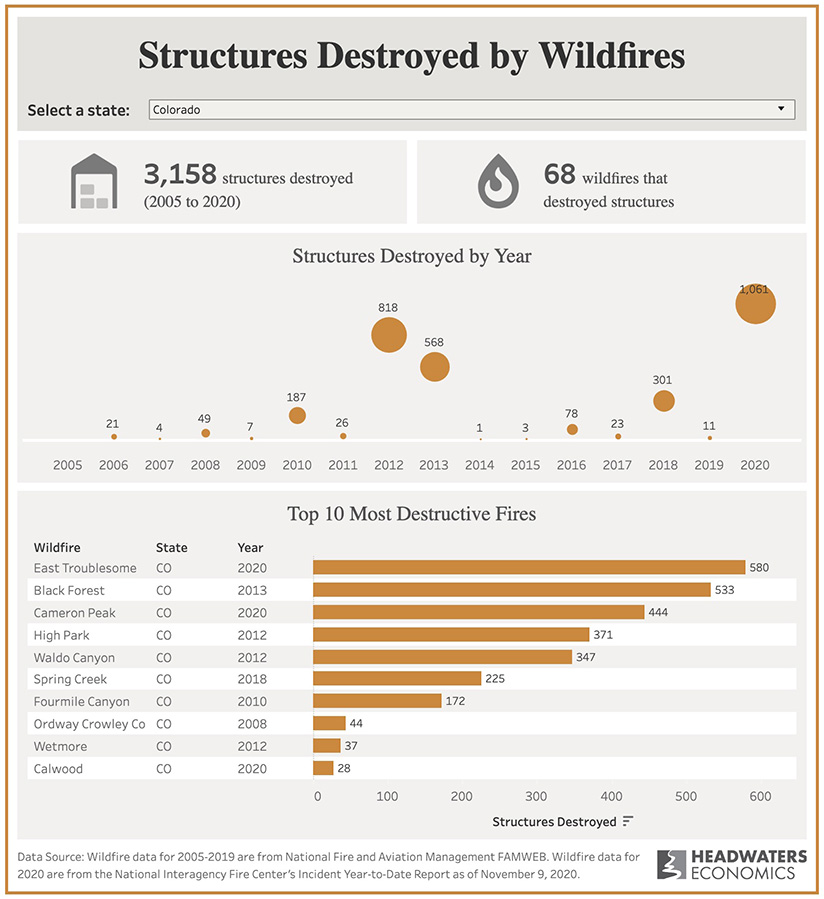

A Facilitated Learning Analysis (FLA) found that 76 workers at the Cameron Peak Fire west of Fort Collins, Colorado tested positive for the virus and 273 had to be quarantined at various times over the course of the fire. Two were hospitalized, the report said. One was admitted to a hospital near the fire on August 24 and by the 31st was placed on a ventilator. The machine breathed for him while in a medically induced coma until he was weaned off October 7. In December he was released to a rehab center.

The FLA did not provide any details about the second person on the fire that was hospitalized.

NBC News reported August 29 that one BLM employee in Alaska died August 13 shortly after testing positive while on the job. Another was in critical condition at that time.

The U.S. Forest Service confirmed that 643 FS wildland fire personnel had tested positive for coronavirus as of January 19, 2021, according to spokesperson Stanton Florea.

Of those, 569 had recovered by then, Mr. Florea said, but 74 had not yet fully recovered or returned to work as of January 19. At that time there had been no reported fatalities in the FS tied to coronavirus, he said.

When we asked in January, the Department of the Interior refused to release any statistics about COVID-19 positive tests, hospitalizations, or fatalities among their range or forestry technicians who have wildland fire duties. Spokesperson Richard Parker wrote in an email, “We respectfully decline to comment further on this topic at this time.”

Four land management agencies in the DOI employ fire personnel, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Indian Affairs, Fish & Wildlife Service, and National Park Service.