(Originally published at 2:07 p.m. MT, April 5, 2013; updated at 4:30 p.m. MT, April 5, 2013)

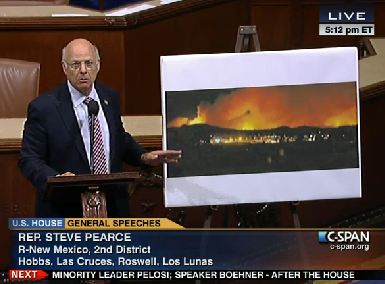

The City of Colorado Springs has released a second report about the disastrous Waldo Canyon fire that in June, 2012 killed two people, destroyed 347 homes, and burned 18,247 acres. The first report can be found HERE, and was called an “Initial After Action Report” considered preliminary. Wildfire Today covered that report on October 23, 2012. This new report on the City’s web site is described as the “Final After Action Report”. Unlike the first version, this one provides more information about what went well and what didn’t, and includes many recommendations along with the reasons for each one.

As a firefighter who worked on the 1975 Pacoima Fire where the Incident Command System was used for the first time, it is difficult to understand why 37 years later a large city with an extensive wildland/urban interface in a wildfire-prone area had not fully adopted the ICS by 2012. In reviewing these two reports, and an excellent exposé written for the Colorado Independent by Pam Zubeck, which in my mind deserves a Pulitzer Prize, roughly 75 percent of the problems identified could have been avoided if Colorado Springs had fully implemented the ICS.

The City’s reports claim ICS training has been conducted for some of their employees, but it is clear from the problems encountered during the Waldo Canyon Fire that it was poorly, if at all, implemented.

Even if extensive ICS training is given within the City, that is not enough. The system needs to be used daily. No one can receive the training and then instantly be qualified as a Logistics Section Chief, for example. Under the best of circumstances, it takes years, sometimes decades of experience and training to advance from an entry level ICS position to the highest ranks, so Colorado Springs needs to develop an aggressive mentoring program. Trainees need to be assigned on large incidents outside the City to shadow someone who can show them the ropes. Their freshly trained employees may not qualify for a Trainee position at the Unit Leader or Section Chief level, but I doubt if the City will worry much about qualifications for ICS positions, or how to move up the chain of command from position to position. The 310-1 Wildland Fire Qualification System Guide might only be a pipe dream for Colorado Springs.

This in no way should be considered as criticism of the Colorado Springs firefighters. Many of them are highly trained and some have had multiple assignments with Type 1 incident management teams on large wildfires. The organizational and policy problems rest with the city administrators and the leaders within the fire department.

The Colorado Springs Gazette published an article about the report on April 3, pulling no punches. Here is an excerpt:

“Obviously, going forward we need to learn from this. If this fire had started on Cheyenne Mountain we would have lost thousands of homes and probably many more people,” [Mayor Steve Bach] said Wednesday. “This is going to happen again.”

The report focused largely on the afternoon and night of June 26, when the fire destroyed 347 homes and killed two residents.

Colorado Springs firefighters raced into Mountain Shadows without plans to ensure they had food, water or rest breaks, the report said.

Capt. Steve Riker, the department’s incident commander on June 26, said he initially had his firefighters “well under control.” However, he said that control began to slip as units from neighboring fire departments rushed to help.

Supervisors operated under organizational charts that weren’t fully developed, the report said, and emergency plans were “underutilized.”

Communication lagged between city officials and first responders in the field — leading firefighters and police officers to work without full situational awareness.

The Colorado Springs city administration has been sensitive to criticism about they way they managed the fire. In a video that was shot at a press conference, Chief Rich Brown said:

The hypercritical view by some at times just gets a little old. Because of the fact that they weren’t there. They didn’t see what the decision maker at the time saw. Any public safety professional worth anything is always going to come back and say I would have done this differently if I had the same thing to do over again.

Thanks go out to Dick