Above: The new 40-foot fire lookout tower at Big Pocono State Park in Monroe County, PA is one of 16 that are replacing old towers. Penn. Dept. of Conservation and Natural Resources photo.

By Michael Guerin

Even in our technologically advanced age, most reports of fires are called in by observant folks, often using cellphones. The ubiquity of these devices means an increased ability to detect wildfire more quickly. But a fair portion of California still has poor or no cellular coverage. Utilities that shut down power as a wildfire-prevention measure in fire-danger zones also render cellphones in many areas unusable as cell towers lose power.

And as crowded as California can seem, large areas of the state are relatively unpopulated, not dense with residents or hikers who might quickly report a fire. Yet a key firefighting tool that existed in the pre-cellphone era is missing — watchers who were paid to scan the horizon for fires.

At one point, there were more than 9,000 lookout towers in the United States, placed atop hills and mountains where individuals — also referred to as lookouts — worked alone each summer to watch for and report fires. They were adept at recognizing a tiny puff of color against the backdrop of trees, hills or brush for what it can be — the start of what may be the next big fire. An estimated 500 are still staffed across the nation.

California once had about 600 such towers, under federal, state and local control, scattered around forest and wildland ridges and high points, placed specifically for the broad field of view each site afforded. In the Angeles National Forest and surrounding county wildland areas, 24 lookouts watched for our safety.

The state alone employed watchers in as many as 77 towers at one time. The California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection now operates 38 towers, and they are only staffed by employees on occasion. None of these is in Southern California.

In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a growing belief that air pollution had decreased visibility at some sites, and the creep of suburbia and population into the hills and valleys made these watchers seem less necessary. Then there were the cost savings, however modest.

To help address California’s 2003 budget shortfall, the agency that became CAL FIRE offered up the remaining state lookout staffing for a whopping saving of $750,000. By then most towers in the southern national forests and those operated locally by counties or CAL FIRE were gone, repurposed or used as museum pieces.

Today, the U.S. Forest Service mainly hires lookouts for towers in its far northern forests.

Enter the volunteers, including me. Each summer day we staff 11 towers in the Angeles, Cleveland and San Bernardino national forests. Volunteers also watch from at least 16 Forest Service and CAL FIRE towers in Central and Northern California.

We spend thousands of hours each fire season watching over the wildland — and the wildland-urban interface in which many of us live. We constantly scan the landscape with binoculars, watchful humans in constant touch with the dispatcher who can immediately send in the firefighting cavalry. As I scan for “smokes” I often gaze at the peaks that used to have staffed towers, and calculate how much more land we watchers could help protect.

Given our increasingly devastating fire seasons in California, the state should consider reintroducing a wider system of lookout towers, staffed by both paid personnel and volunteers. While budgets may be stretched, staffing an existing tower is not prohibitively expensive.

U.S. Forest Service seasonal lookouts make about $16,000 per summer. By comparison, the valuable Boeing 747 Air Tanker often seen dropping water and fire-retardant substances on California’s devastating fires costs $16,500 an hour to operate.

Many states have ended their lookout programs, but Pennsylvania decided to refurbish its lookout towers and invest in new ones. The state recently built 16 new towers for $6 million, each to be staffed during periods of high danger.

Other detection technologies such as satellite and automated camera systems that might sense a smoke plume could be vital in detecting these seemingly endless fires. But the technology is not infallible.

For instance, the fire-detection camera that may have been closest to the origin of last year’s deadly and destructive Camp Fire in Northern California’s Butte County might have been able to provide an early alert, but its alarm had been turned off as a result of many false alarms, according to news reports.

Few first reports of fires come from cameras, a CAL FIRE spokesman said. They are most often used to monitor fires already reported. Volunteers from the Forest Fire Lookout Assn. are working with researchers to refine these capabilities, and California Gov. Gavin Newsom has allocated $1.6 million for a prototype system for satellite-based detection.

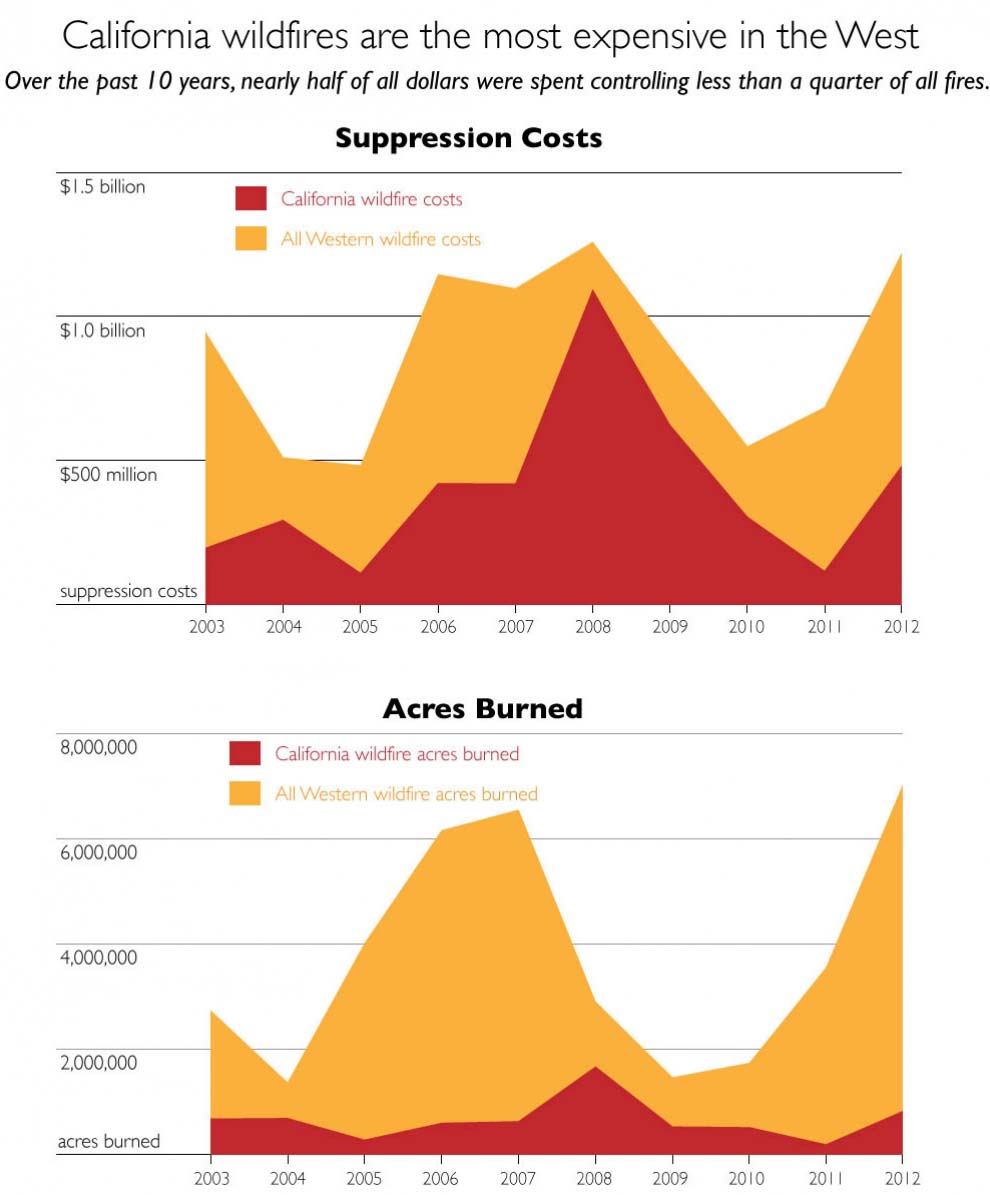

Lookouts and their towers should not be regarded as a sentimental anachronism. They are a critical tool awaiting California’s renewed investment — and might help reduce the state’s fire-suppression costs, which reached $635 million during the 2018-19 fiscal year.

Automation may get to a point where it can more easily detect small fires, but it is not there yet. We still need to rely on old-fashioned human lookouts who are trained to “catch them small.”

Michael Guerin had a 38-year career in public safety and emergency management. While never a firefighter, he worked for the California Office of Emergency Services for 15 years, advancing to the post of Assistant Director for Emergency Operations, Plans and Training. For the past several years he has been a volunteer fire Lookout with the San Bernardino National Forest, helping staff the Red Mountain tower in Riverside County.

The article is used here with Mr. Guerin’s permission. It first appeared in the Los Angeles Times.