The National Institute of Standards and Technology has released a lengthy report on the Waldo Canyon Fire that burned 344 homes and killed two people in Colorado Springs, Colorado in June, 2012. (It can be downloaded here, but is a large file.)

The National Institute of Standards and Technology has released a lengthy report on the Waldo Canyon Fire that burned 344 homes and killed two people in Colorado Springs, Colorado in June, 2012. (It can be downloaded here, but is a large file.)

The 216-page document covers firefighting tactics, how structures ignited, defensible space, and how the fire spread, but does not address to any significant extent the management, planning, coordination, and cooperation between agencies, which were some of the largest issues.

The report was put together by five people, Alexander Maranghides, Derek McNamara, Robert Vihnanek, Joseph Restaino, and Carrie Leland.

At least three official reports have been written about the Waldo Canyon Fire, two from the city of Colorado Springs (here and here) and a third from the county sheriff’s office. However one of the most revealing was the result of an independent investigation by a newspaper, the Colorado Springs Independent, which revealed facts that were left out of the government-issued documents, including numerous examples of mismanagement by the city before and during the event.

The fire was first reported the evening of June 22, 2012 on the Pike National Forest. Due at least in part to the anemic response from the U.S. Forest Service, the fire was not located until after noon the following day. No aircraft were requested until firefighters were at the fire, more than 16 hours after the initial report.

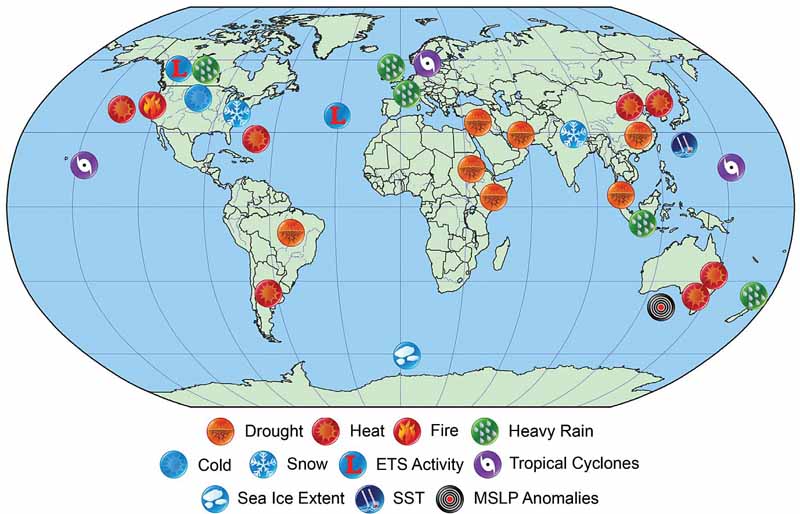

The day the fire started there were eight large fires burning in Colorado and 16 uncontained large fires in the country. Four days later on June 26 when the Waldo Canyon Fire moved into Colorado Springs burning 344 homes and killing two people, there were 29 uncontained large fires burning in the United States.

However there were only nine large air tankers in the United States on U.S. Forest Service exclusive use contracts, down from the 44 we had 10 years before.

The 7-page Executive Summary of this newest report lists 4 primary findings, 37 technical findings, and 13 primary recommendations.

Primary findings:

- Defensive actions were effective in suppressing burning structures and containing the Waldo Canyon fire.

- Pre-fire planning is essential to enabling safe, effective, and rapid deployment of firefighting resources in WUI fires. Effective pre-fire planning requires a better understanding of exposure and vulnerabilities. This is necessary because of the very rapid development of WUI fires.

- Current concepts of defensible space do not account for hazards of burning primary structures, hazards presented by embers and the hazards outside of the home ignition zone.

- During and/or shortly after an incident, with limited damage assessment resources available, the collection of structure damage data will enable the identification of structure ignition vulnerabilities.

Three of the technical recommendations:

- Fire departments should develop, plan, train and practice standard operating procedures for responding to WUI fires in their specific communities. These procedures should result from scientifically mapping a community’s high- and low-risk areas of exposure to both the fire and embers generated during WUI events (as will be possible using the WUI Hazard Scale).

- A “response time threshold” for WUI fires should be established for each community. Fire departments have optimal “time-to-response” standards for reaching urban fires. Similar thresholds can, and should be, set for WUI fires.

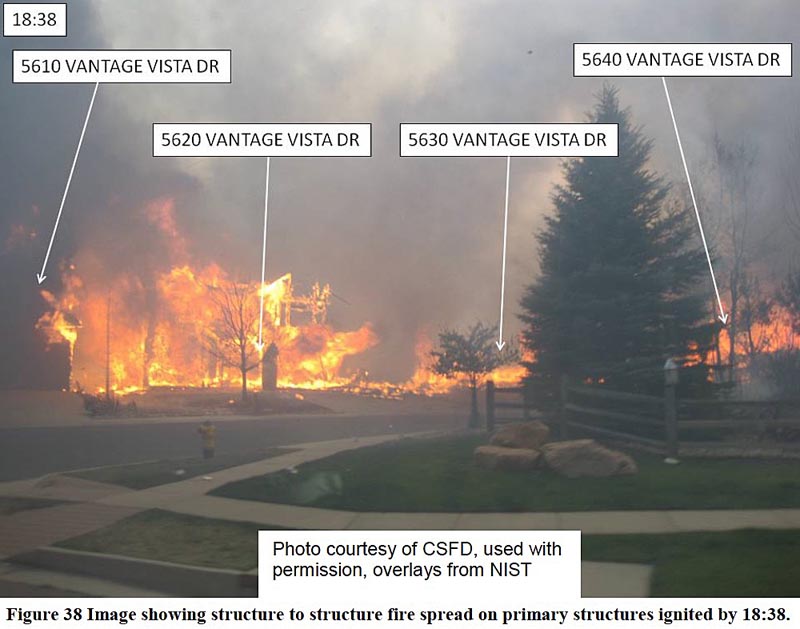

- High-density structure-to-structure spacing in a community should be identified and considered in WUI fire response plans. In the Waldo Canyon fire, the majority of homes destroyed were ignited by fire and embers coming from other nearby residences already on fire. Based on this observation, the researchers concluded that structure spatial arrangements in a community must be a major consideration when planning for WUI fires.

Primary recommendations: