Both houses of Congress passed a 5,600-page omnibus spending package Monday night to fund numerous programs that included the Departments of Agriculture and Interior along with COVID-19 relief. It the bill is signed by the President it will fund the agencies during the fiscal year that began October 1, 2020.

There are no major changes in the appropriations for wildland fire activities that employ approximately 15,000 forestry and range technicians whose primary duties are fighting wildfires. But there are some interesting issues that were highlighted, not in the text of the bill itself, but in the “explanatory statement” that elaborates on Congress’ oversight of the fire programs in the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Firefighting Technologies

Congress reminded the five agencies that the John D. Dingell, Jr. Natural Resources Management Act that passed overwhelmingly in both houses almost two years ago requires that by March 12, 2021 they develop and operate a tracking system to remotely locate the positions of fire resources. According to a press release by Senator Maria Cantwell at the time, by the 2021 fire season all firefighting crews – regardless of whether they are federal, state, or local – working on large wildfires will be equipped with GPS locators. By September 8, 2019 they were also supposed to develop plans for providing real-time maps of the location of fires. We have referred to knowing the real time location of both the fire and firefighters working on the fire as the “Holy Grail of Wildland Firefighter Safety.”

Apparently worried that the five agencies may be dragging their feet in following the requirements in the bill (which became law), Congress very, very politely issued a reminder in the explanatory statement:

The Committee encourages increased investment in these technologies within the funds provided for Forest and Rangeland Research and for preparedness activities in Wildland Fire Management. The Committee encourages prioritizing the use of commercial, off-the-shelf solutions, including mobile MESH networking technology, that provide situational awareness and interoperable communications between federal, state, and local firefighting agencies.

Longer contracts for firefighting aircraft?

The explanatory statement has a surprisingly lengthy section that directs the Forest Service and the DOI to submit a report within 90 days that lays out the considerations of awarding 10-year contracts for aircraft available for wildland fire suppression activities. If the President signs the bill today, the report would be due March 22, 2021.

The Next Generation 3.0 contracts for five large air tankers announced in October are for only one year with the possibility of up to four more years at the discretion of the FS.

Fire Aviation has more details about the possibility of longer contracts.

Move the Forest Service Fire and Aviation section out of State and Private Forestry

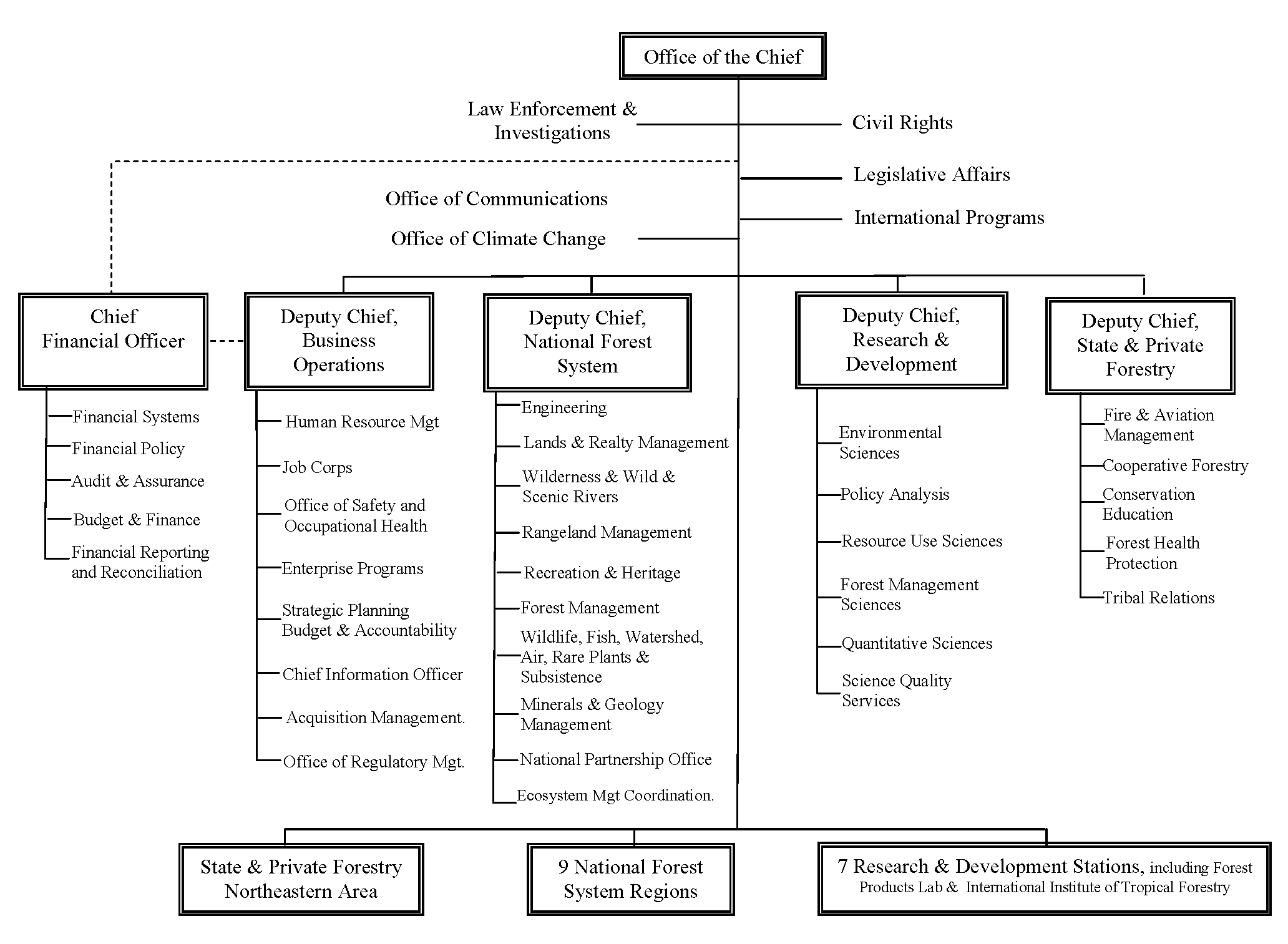

More than half of the entire budget of the Forest Service goes to Fire and Aviation Management (FAM). But if you were trying to find FAM on the agency’s organization chart, it may take a while.

The first version of the appropriations bill introduced in the Senate required that FAM be moved out of State and Private Forestry and put in it’s own branch, with the Director of FAM becoming a Deputy Chief:

Commensurate with the modernized budget structure included in this Act, the Forest Service shall realign its Deputy Chief Areas to conform to the appropriations provided herein, including the creation of a Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation to administer the Wildland Fire Management appropriation, within one year of enactment of this Act.

In November the National Association of State Foresters wrote a letter to the House and Senate appropriations leadership opposing the concept:

While we agree more must be done to minimize the threat of catastrophic wildfire, we are concerned that establishing a Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation would divert valuable resources from land management activities that reduce the threat of wildfire, only to establish additional bureaucracy around wildfire suppression… Establishing a Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation is tantamount to building a “fire agency” and therefore contrary to the intent of the “Wildfire Funding Fix,” which Congress passed to free up funding for more active forest management.

The final version of the bill that passed Monday night eased off on that requirement, suggesting the agency just think about it:

The Committees are interested in data and recommendations relating to any changes that could be made to improve the representation of Wildland Fire Management leadership under this structure and the potential creation of a new Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation. The Committees recognize that wildland fire related activities touch every aspect of the agency and believe that providing the fire function with a senior leadership role at the Service will improve coordination and better represents the role fire plays in agency budgeting and decision making.

Last week before the new language became available Monday night I checked with some fire management folks, asking their thoughts about the requirement, at the time, of promoting FAM to be their own branch with a Deputy Chief for Fire and Aviation. Here are their responses, in some cases edited for brevity:

Tom Harbour, former Director of FAM for the Forest Service:

The language is controversial. Specific organizational language like this is not popular with any federal organization. Based on just budget, the FAM program has been “Deputy Chief eligible” for a couple decades, but more goes into significant organization change decisions than budget. Five different Chiefs (Bosworth, Kimball, Tidwell, Tooke, Christiansen) have had the budget facts in front of them and have decided NOT to make a change. The most obvious immediate question is what would happen with S&PF programs, and what happens with the important relationships with State Foresters?

Greg Greenhoe, former Deputy Director of Fire and Aviation Management for the Northern Region, USFS

I really don’t know enough about the issue to have an opinion. I can understand the concern of the State Foresters with Fire Management leaving State and Private. But even when I was still working I always thought it was strange that Fire was under State and Private. I can see that some folks would be concerned that the largest single budgeted function in the FS doesn’t have its own Deputy Chief.

Kelly Martin, former Fire Chief of Yosemite National Park, National Park Service

Due to the fact that the wildland fire budget for suppression and preparedness is an overwhelming part of the entire USFS budget, this new proposed Deputy Chief of Fire and Aviation Management (FAM) position reporting directly to the Chief of the USFS leads to better accountability between the Chief of the USFS and the Fire and Aviation program. Much needed modern reforms and developing a “National Fire Plan 2.0” will need to be closely linked between the Chief of the USFS and the Dep Chief of FAM. State and Private Forestry will continue to be an important part of the USFS overall program with or without the Fire Director working directly for the Deputy Chief of SPF.