By Matt Vasilogambros

As wildfires continue to burn in parts of the United States, state public health officials and experts are increasingly concerned about residents’ chronic exposure to toxin-filled smoke.

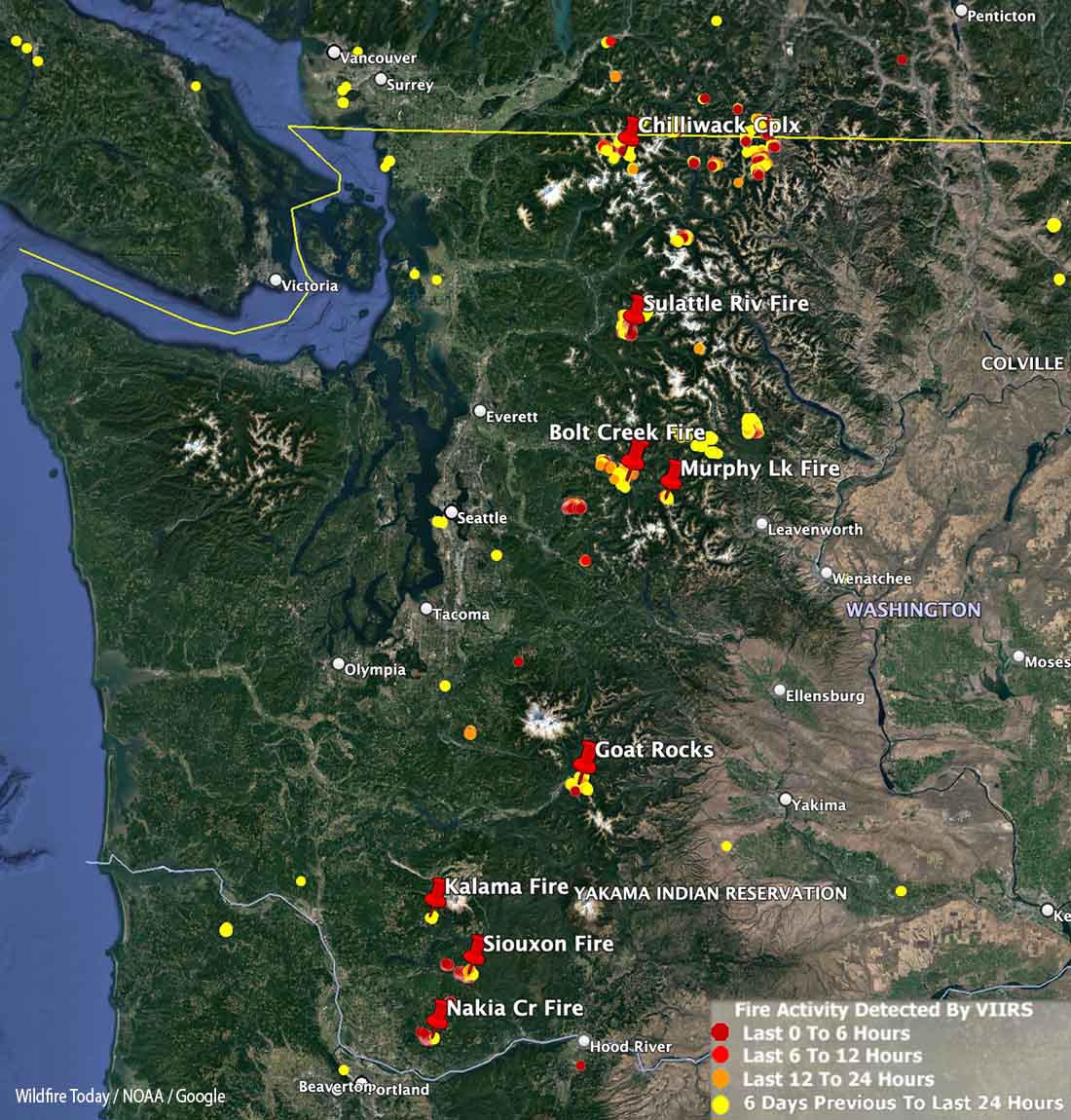

This year has seen the most wildfires of the past decade, with more than 56,000 fires burning nearly 7 million acres nationwide, according to the National Interagency Fire Center. While the total area burned is less than in some recent years, heavy smoke has still blanketed countless communities throughout the country.

Climate change is causing more frequent and severe wildfires, harming Americans’ health, pointed out Dr. Lisa Patel, deputy executive director at the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, which raises awareness about the health effects of climate change.

“The data we have is very scary,” she said. “We are living through a natural experiment right now — we’ve never had fires this frequently.”

Patel sees the effects of wildfires in her work as a practicing pediatrician at Stanford Medicine Children’s Health, treating more women and underweight and premature infants at the neonatal intensive care unit when wildfires rage in Northern California.

As researchers focus on the public health impact of wildfire smoke, state health and environmental officials across the country have had to issue more air quality notices and provide guidance and shelter for residents struggling during periods of heavy wildfire smoke. And as experts have found, this issue isn’t isolated to the West Coast — it hurts more residents in the Eastern U.S.

Studies show that chronic exposure to wildfire smoke can cause asthma and pneumonia, and increase the risk for lung cancer, stroke, heart failure and sudden death. The very old and very young are most vulnerable. Particulates in wildfire smoke are 10 times as harmful to children’s respiratory health as other air pollutants, according to a study in Pediatrics last year.

What concerns experts is particulate matter in the air smaller than 2.5 microns across; there are around 25,000 microns in an inch. People inhale these microscopic bits, which then can embed deep in their lungs, irritating the lining and inflaming tissue. The particles are small enough to get into a person’s bloodstream, which can lead to other short- and long-term health effects.

Particulates in wildfire smoke are even hindering national progress on reducing air pollution, after decades of improvement.

The federal Clean Air Act has substantially decreased the level of toxic particles from industrial and automotive pollution across the country since 1970, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency notes. But air pollution is expected to worsen in parts of the West because of wildfires, some researchers have found. A United Nations report earlier this year warned of a “global wildfire crisis,” saying the probability of catastrophic wildfires could increase 57% by the end of the century.

Researchers are trying to better understand how more frequent wildfires affect human biology.

Keith Bein, associate professional researcher at the University of California, Davis, created a rapid response mobile research unit in 2017 that he deploys when there are fires around the state. He’s like a storm chaser but for wildfires.

With his mobile unit, Bein can measure particulate matter in the air, take samples back to his lab and then determine their toxicology and chemical compositions. When near these fires, he said, the smoke is so bad that it feels like there’s no escaping it.

“The smoke rolls in, and you get that sinking feeling all over again,” he said.

Massive wildfires that tear through communities are becoming more common. The fires aren’t just burning trees but also synthetic materials in homes. And with repeated exposure to different particulates, health risks are more pronounced and can evolve into chronic conditions, Bein said.

Researchers are just beginning to understand how more frequent wildfires in residential areas impact human health, he added.

“It’s happening more frequently every summer,” he said. “The length of the fires is growing. The public exposure to the smoke is also growing. Once-in-a-lifetime events are happening every summer. This is a different kind of exposure.”

In 2020, a study in Environment International found that winter influenza seasons in Montana were four to five times worse after bad wildfire seasons, which typically last from July until September. The findings shocked study lead author Erin Landguth, an associate professor at the University of Montana.

“We know that hospitalizations for asthma and other respiratory conditions spike within days or weeks of wildfires,” she said. “The thought that this could potentially lead to effects later and how that can affect our immune system is really scary.”

Landguth is currently expanding her study to all Western states. She expects to find a similar trend throughout the Mountain West and Pacific Northwest. Monsoon season in Arizona and New Mexico may disrupt the trend there, she said, while air pollution is already so bad in California from smog and other pollutants that it might be difficult to pinpoint how wildfires are harming human health.

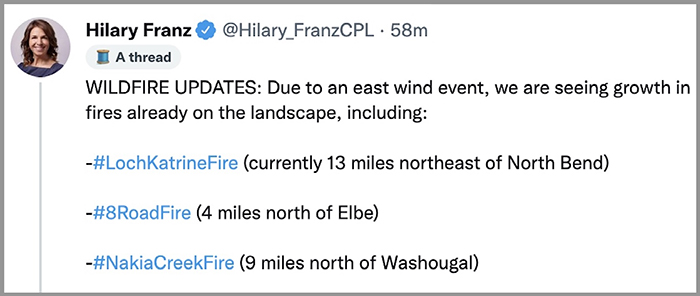

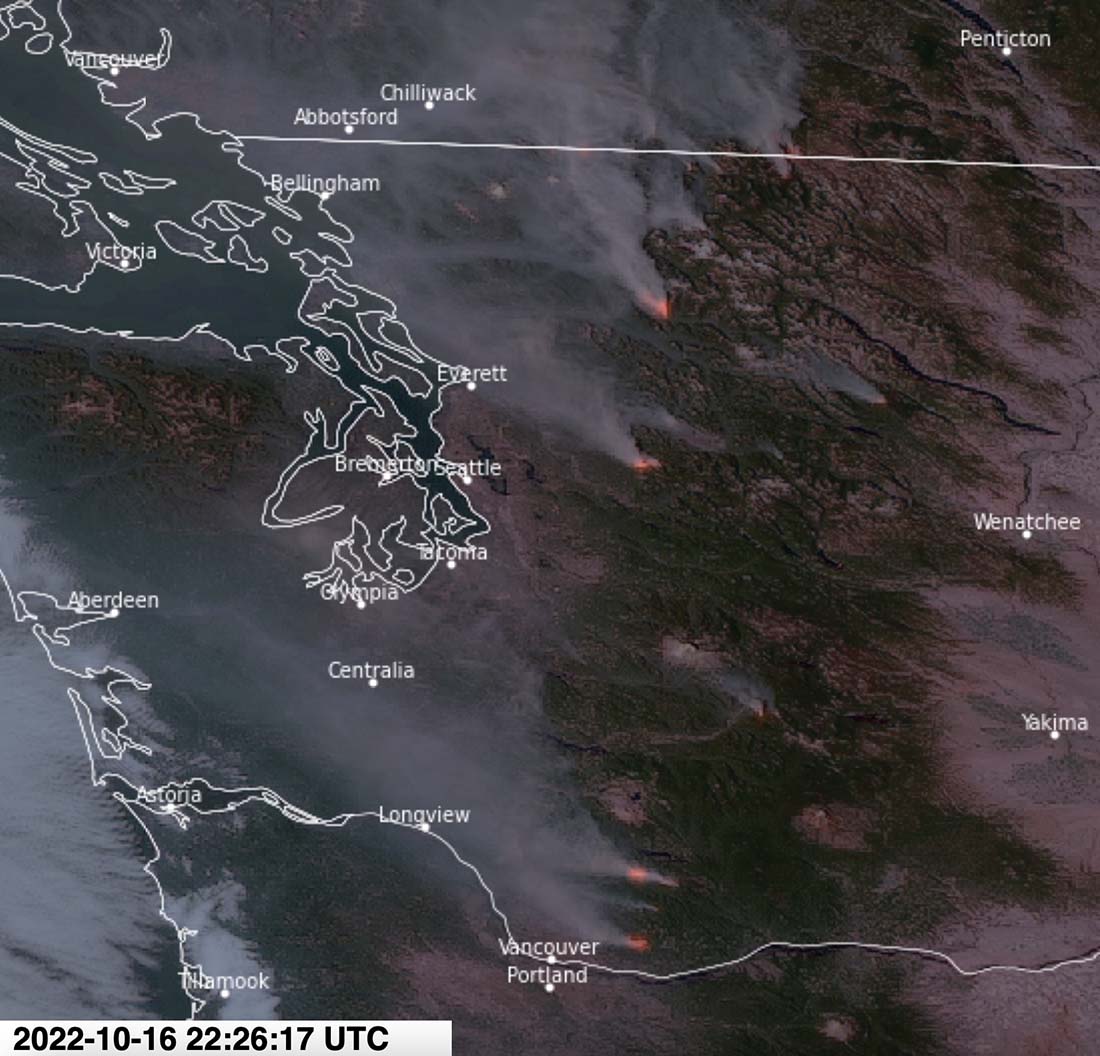

But wildfires are not just in the West, nor is their health impact geographically isolated. Some fires burn so intensely at such high temperatures that smoke rises into the atmosphere, where strong winds can carry the smoke long distances.

This was glaringly apparent in 2021 when the sun glowed red, and the sky hazed over New York City and throughout the Northeast, as smoke drifted from massive wildfires in California, Oregon and other Western states.

That smoke is hurting the health of more people in the Eastern U.S. than it is in the West, said Katelyn O’Dell, a postdoctoral research scientist at George Washington University, who released that finding in a study in GeoHealth in 2021. Wildfire smoke contributed to more asthma-related deaths and hospital visits in Eastern communities than those in the West, she and other researchers found, in part because of higher population density.

The smoke hitting the Eastern U.S. doesn’t just come from the West; there are wildfires and prescribed burns throughout the country, said O’Dell.

“It’s sometimes easy to feel distant from fires and their impacts when you’re far from the flames of these large Western wildfires that are in the news,” she said. “But wildfires impact the health of the U.S.”

The next orange sunset people enjoy should be a moment to check an air quality mobile app, she said.

In Minnesota, the state has issued 46 air quality alerts since 2015, according to the state’s Pollution Control Agency. Of those, 34 were due to wildfire smoke, and 26 of those were issued last year.

That took state officials by surprise, said Kathy Norlien, a research scientist at the Minnesota Department of Health. The wildfire smoke risk is not just coming from the plumes that drift from the West Coast and Canada, but also from wildfires in the Boundary Waters — a lake-filled region in the northern stretches of the state. She expects the problem to worsen in the coming years.

“At this point, we’re planning for the worst-case scenario,” she said. “We have not had the extent that the Western states have had. But with climate change and concern over drought and the dry conditions, planning is of the utmost importance.”

She meets regularly with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and other state officials about how to get the message to state residents about the increasing wildfire risk to public health, encouraging residents to sign up for air quality alerts. State officials also have established larger community centers and buildings as safe air shelters.

The public plays an enormous role in both preventing (nearly 90% of wildfires are caused by humans, according to U.S. governmental data) and adapting to wildfires, many experts say.

For people living in fire-prone areas, there are nonflammable building materials for new homes and indoor air purifiers and upgraded HVAC systems. But these solutions may be too costly for some families, said Patel, of Stanford Medicine.

She counsels families about how to affordably stay safe during wildfire season, encouraging the use of N95 and KN95 masks, which were pivotal in combating the spread of the coronavirus. She also shares designs for do-it-yourself air filtration systems.

But she emphasized that wildfires will continue to rage across the country and cause adverse health effects unless climate change is reined in through serious public policy. Until then, climate change will continue to be the biggest threat to public health, she said.

“Summer used to be a time I’d look forward to,” she said, “but now I look at it with dread with the heat and wildfires.”

First published by Pew Charitable Trusts on Stateline. Used with permission.