By Murry Taylor

The big man leaned across the table, folded his hands, thought for a moment, then said that he wanted to make one thing clear right from the beginning: What we did on our forest this summer was partly due to the specific character of our geography, our climate, our roads, our fuels, and about mitigating future risks. All new fires during fire season received a full-suppression, aggressive initial attack approach. The big man who made this statement was Merv George, Jr., Supervisor of the Rogue River–Siskiyou National Forest (RRSNF) in southwest Oregon. And the What-we-did Merv was referring to was to initial attack 60 fires and keep the total acres burned at a little over fifty for the year. Note that in the summer of 2020, they had the same number of fires and only burned 20 acres. That is not counting the Slater Fire that came onto their forest from the Klamath N.F. and burned way up into Oregon. No fault there given it was unstoppable right from the beginning. Sitting not far from Merv was Dan Quinones (RAC ’02)- a former Redmond smokejumper, and the FMO on the RR–Siskiyou. Note, I’m not using quotation marks with these statements unless I can remember exactly what was said. Words are important to these two men. I want to make sure that’s understood.

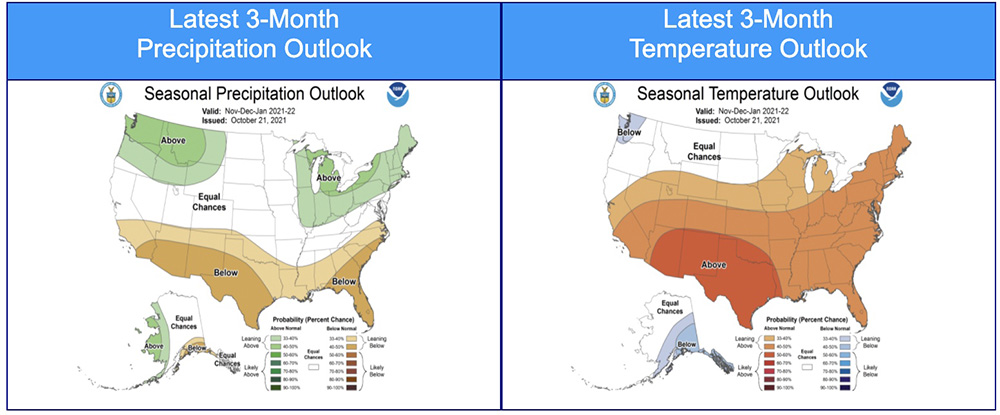

Given the heartbreaking news of Western fires during the 2021 fire season, it was a breath of fresh air when Chuck Sheley (Editor Smokejumper magazine) and I met with Merv and Dan last October. Many of us, including a lot of Smokejumper magazine readers, have been pushing for years to get the Forest Service back to rapid and aggressive initial attack. Chuck has led the charge and now that effort (in some areas) seems to be paying off. Bill Derr’s (USFS Ret.-Law Enforcement) email thread includes several retired Forest Supervisors, FMO’s, Type 1 IC’s, Operations Chiefs, Deputy Chiefs, and Air Resource Officers. The National Wildfire Institute based in Fort Jones, California has been steadily at it as well. Add in former Forest Service Deputy Chief, Michael Rains’ “The Call to Action,” and James Petersen’s “First Put Out the Fire,” and you have major voices calling for an immediate change in how the Forest Service deals with fire these days. As you would expect, among these people it’s fully acknowledged that fire plays an important role in forest health. But, given the longer fire seasons in the West, the massive forest fuel build-up due to less logging, and the critical low fuel moisture due to climate change, it’s clear that, for the time being, we need to put out all fires during fire season as quickly as possible. It’s also understood that some fires will (even with the best effort) escape containment and go big. So, for those concerned about getting fire back on the landscape, it’s likely that plenty of acres will end up in that category anyway.

That said, you can imagine how excited we were hearing from the Rogue-River Siskiyou N.F. about their IA success in the summers of 2020 and 2021. More on that later but now, some history.

In early summer 2019, Oregon Governor Kate Brown established The Oregon Wildfire Response Council (OWRC). It seemed a good idea. I felt that a state like Oregon might make real progress on the mega-fire issue plaguing the West. First, as a relatively small state, they are more politically agile—certainly more than California. Secondly, the timber industry has had–and still has–a strong influence in Oregon politics. And third, both private industry and the Oregon Department of Forestry (with its emphasis on strong initial attack) have historically leaned on the Forest Service to put stronger emphasis on more aggressive fire suppression.

So, I did some research and contacted Ken Cummings, Regional Manager at Hancock Natural Resources Group in Central Point, Oregon. He was on the OWR Council and put me in touch with Committee Chairman, Matt Donegan and concerned citizen, Guy McMahon in Brookings. Kate Brown’s office wrote back and put me in touch with an aide to Senator Jeff Merkley. Within a month Jim Klump (RDD ’64 – former Redding smokejumper and FMO on the Plumas N.F.) and I went to Salem to attend an Oregon Wildfire Response Council meeting. Senator Merkley’s aid was there. After speaking with both the aide and Matt Donegan about what might be done locally, I decided to contact my two local Forest Supervisors, Merv George Jr. on the Rogue River-Siskiyou and Rachel Smith on the Klamath.

When Merv George Jr. agreed to our first meeting (that was in June), I took a half-dozen copies of Smokejumper magazine to give to him. These were the ones in which Chuck beat the “strong initial attack and keep them small” drum hard. Early in the meeting, not long after I’d brought up the subject of strong IA, Merv leaned forward and told me straight-faced, you’re looking at one of the most aggressive IA Forest Supervisors you’ve ever met. He went on to explain that his Hoopa Native American heritage has helped him understand the difference between “good” fires and the devastation that “bad” fires can cause. He also understands the need to put fire back in the woods and, more importantly, the right times to put it there. He went on to explain that he raised his hand for the RRSNF position to try to “fix” the problem. The “problem” being the large fires of late on the forest—the Chetco Bar, (192,000 acres), the Klondike (175,258 acres), and the Taylor (53,000 acres) to mention three. That got me thinking that there could be a big success story if the Rogue River–Siskiyou could showcase that, with the right preparedness and IA effort, you could put out most all fires.

Then, while serving as Duzel Rock Fire Lookout (for Cal Fire) this summer, I got a call from Dan Quinones. That was late July. At that point, they had had 48 total fires, 31 lightning and 17 man-caused. Total acres burned, less than ten. Then he said the other thing (when added to Merv’s comment about being an aggressive IA Forest Supervisor) that made me want to write this article: “Our crews are going around with smiles on their faces. We’re having fun.” I thought to myself, this is it. This is what most old-time firedogs have been saying all along. If you encourage your crews to get out there and go after fires and put them out small, they will naturally become excited and connect with the passion of good firefighting.

Such passion comes directly from successful initial attack. It comes from those times when a crew hits a fire, works into the night, works until they feel tired and hungry and miserable but keep going, digging deep and finding that better part of themselves. That part they instinctively hoped was there. Then, once they catch their fire and walk off the mountain in the morning they feel like kings, and nothing can ever take that feeling away. It’s the tough times that build the kind of character that make great wildland firefighters. The tough times are transforming, and they are empowering. I think this point is not widely understood by many current wildland fire managers. Time after time I’ve heard from various crews, “Murry, they’re ruining firefighting. They’re holding us in camp too much. They’re not letting us do our job.”

I heard it again this past summer and not just from crews but from a Central California Type 1 Incident Commander, his Ops Chief and Plans Chief. Their take: Too many times effective work could have been done. Too many times crews and related resources were held back by the local forest. The IC told me straight out, “It’s this safety thing. The safety card is played too much. Too many times it’s too steep and it’s too rough. He went on to point out that by backing off and slacking off, these fires go way big and expose crews to thousands of miles of road trips—often when exhausted–thousands of helicopter rides into unimproved helispots and tens of thousands of miles of fireline with burning trees and snags.”