Six months ago we wrote about a project by the First Street Foundation which claimed to have developed a system for calculating the wildfire risk of 145 million properties in the United States.

We tested the system by entering property addresses for homes at two locations that were severely impacted by recent wildfires.

- The Marshall Fire near Boulder, Colorado last year destroyed 1,091 homes and damaged 179. We looked up the Risk Factor for three properties in a community that had total destruction. The result was that they all had a 3 of 10 “moderate fire factor”, and individually a 1.84, 2.0, 1.84 percent chance of being in a wildfire over the next 30 years.

- The Coastal Fire (see photo above) destroyed 20 homes in Laguna Niguel, California and damaged 11. The two we looked at in the zone with severe destruction received a 3 of 10 “moderate fire factor” with a 0.93 and 1.54 percent chance of being in a wildfire over the next 30 years. The homes were at the top of a steep brush-covered slope.

Another system

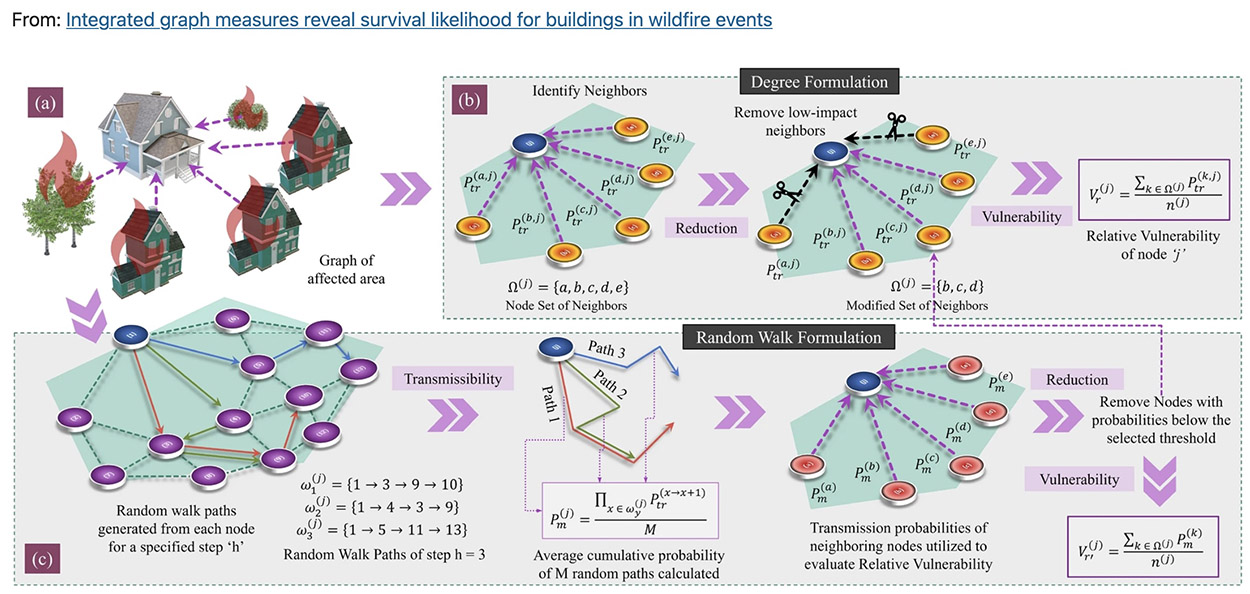

Colorado State University engineers have developed a model that they say can predict how wildfire will impact a community down to which buildings will burn. They say predicting damage to the built environment is essential to developing fire mitigation strategies and steps for recovery.

For years, Hussam Mahmoud, a Civil and Environmental Engineering professor, and postdoctoral fellow Akshat Chulahwat have been working on a model to measure the vulnerability of communities to wildfire. Most wildfire mitigation studies have focused on modeling fire behavior in the wildland; Mahmoud and Chulahwat’s model was the first to predict how a fire would progress through a community.

“We’re able to predict the most probable path the fire will take and how vulnerable each home is relative to the neighboring homes,” Mahmoud said. “We put a spin on the original model that allows us now to determine the level of damage in each building, whether the building will burn or survive.”

Using data from Technosylva, a wildfire science and technology company, Mahmoud and Chulahwat tested their model on the 2018 Camp Fire and 2020 Glass Fire in California. The model predicted which buildings burned and which survived with 58-64% accuracy. Since publishing their results in Scientific Reports, they have predicted which buildings burned with 86% accuracy for the Camp Fire by adjusting how the model weighs certain factors that contribute to damage.

Mahmoud says a holistic approach is needed to understand wildfire behavior and bolster resilience. Models that incorporate a community’s wildland and built environment features will give decision-makers the information needed to mitigate vulnerable areas.

Wildfire is like a disease

To develop their model, Mahmoud and Chulahwat employed graph theory, which is used to analyze networks. These methods also are used to study how diseases spread.

“Wildfire propagation in communities is similar to disease transmission in a social network,” Mahmoud said. Fire spreads from object to object in the same way contagions pass from one person to another.

Wildfire mitigation strategies are like the tactics used to control the spread of COVID-19, he said. A community’s immune system can be boosted by mapping a structure’s surroundings (contact tracing), clearing defensible space around structures (social distancing), reinforcing structures to be more fire resistant (immunization), and creating a buffer zone at the wildland-urban interface (closing borders).

Some homes are like super-spreaders — they are more at risk of fire and more likely to transmit fire to other homes. By targeting certain homes or areas for reinforcement, policymakers could maximize a community’s mitigation efforts, Mahmoud said.

As wildfire risk is compounded by more people moving to wildland-adjacent areas and climate change drying out the landscape in arid regions, the researchers hope their model will help protect communities from the devastating losses wrought by wildfires.

“Fire science is not rocket science—it’s way more complicated.” Robert Essenhigh, Professor Emeritus, Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Ohio State University.