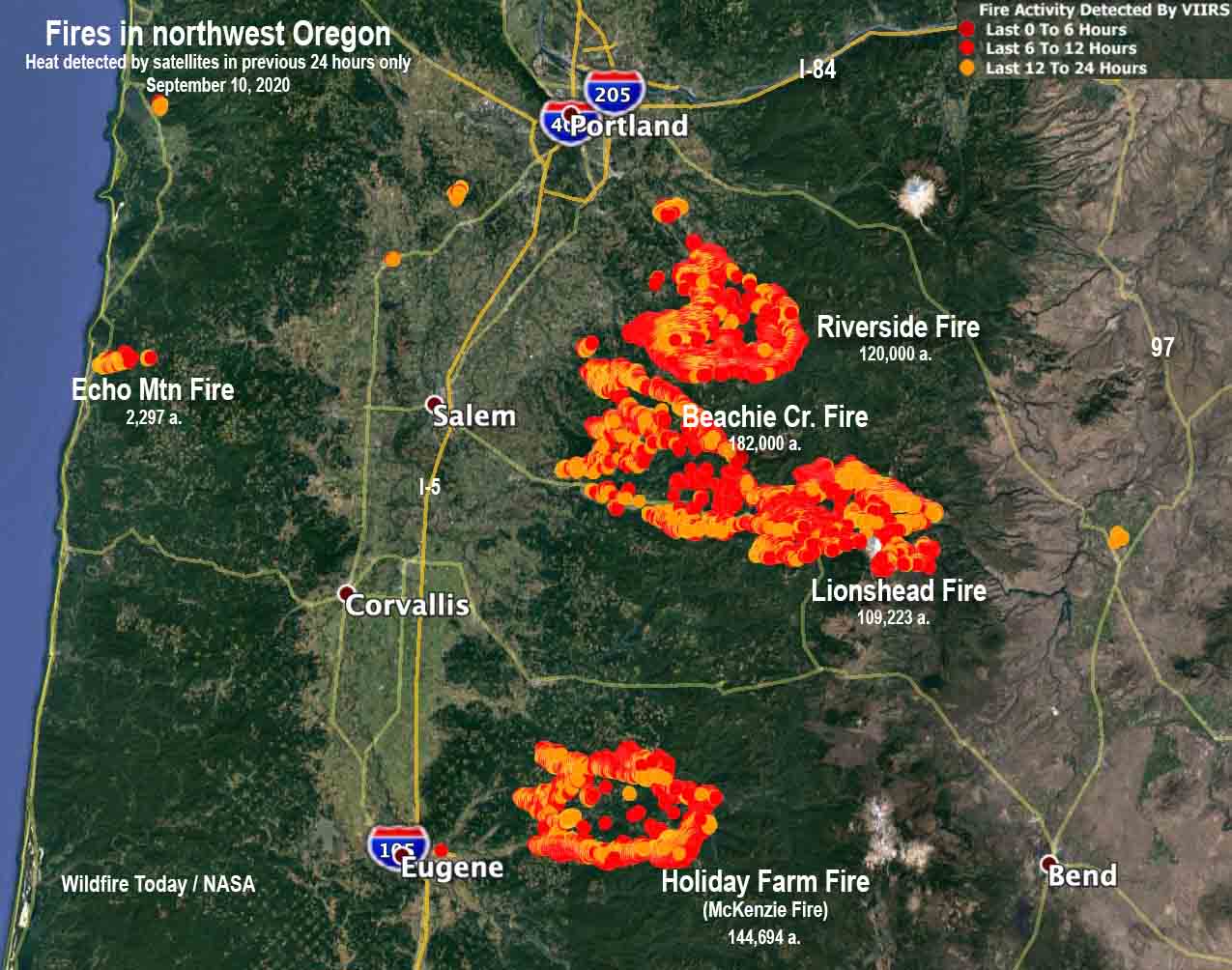

It could take some time to count all of the structures that have burned in western Oregon. What is known so far about the huge fires that have burned approximately a million acres in the state is the deaths of seven people have been documented according to state officials. Dozens more, they said, are unaccounted for, but many of those could be safe and are having difficulty communicating with friends and relatives.

The number of people that have evacuated has been fluctuating wildly. The Oregonian reported that the state in a news release Thursday night said an “estimated 500,000 Oregonians have been evacuated and that number continues to grow.” The half-million figure received widespread attention, but after an analysis by the newspaper determined that number could not be accurate, Gov. Kate Brown acknowledged Friday the true number to be far lower, about 40,000. She explained that the higher figure included everyone in some category of evacuation, including “Be Set,” and “Be Ready.”

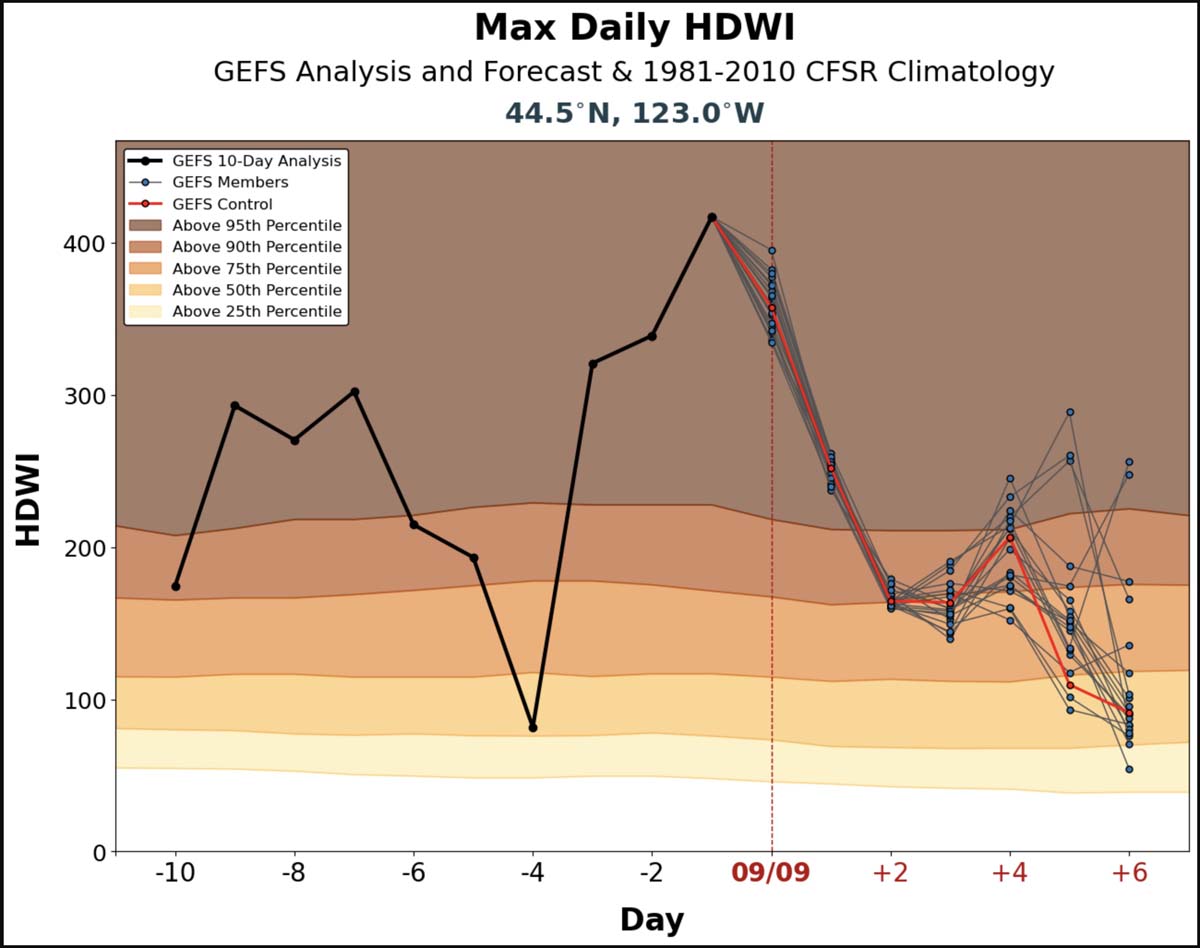

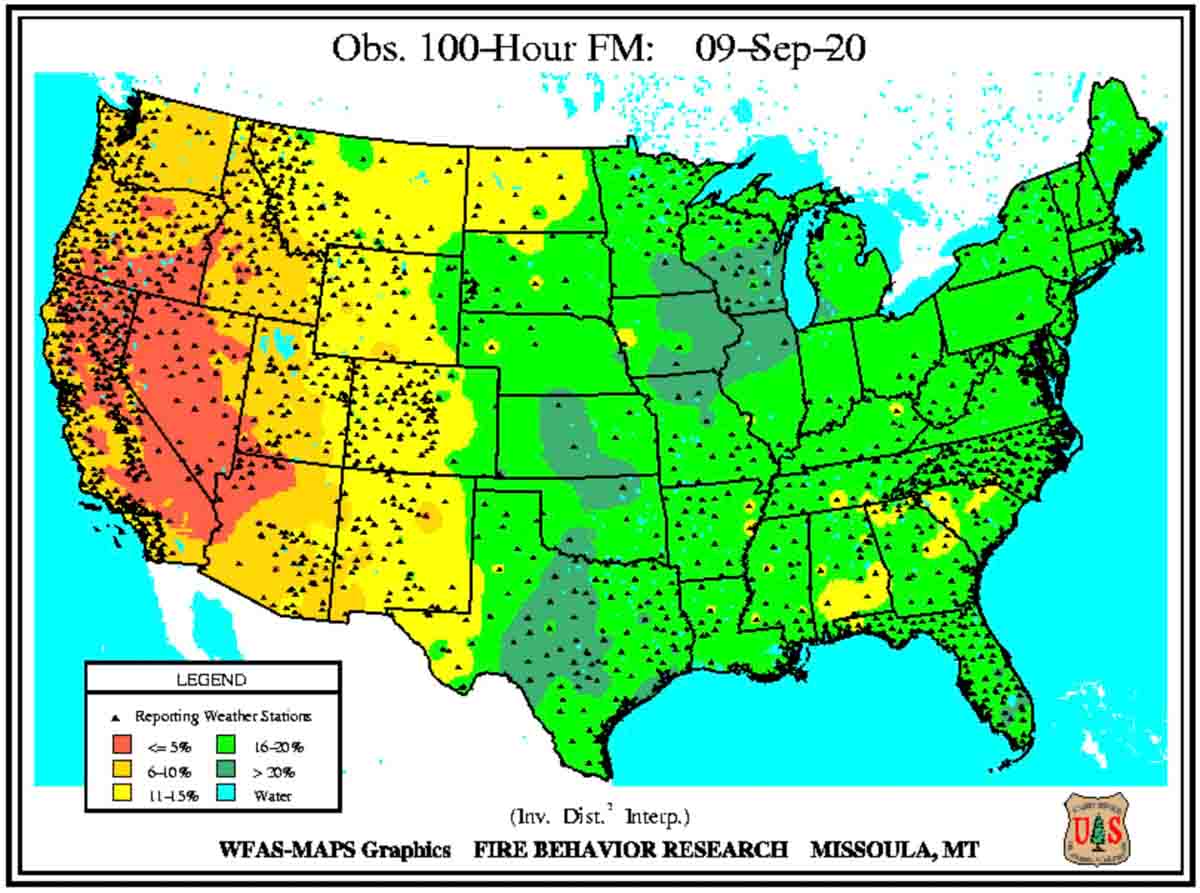

The weather next week is expected to be cooler, with decreasing winds and a slight chance of rain on Tuesday and Thursday. This should slow the spread of the blazes and enable firefighters to shift from evacuations to constructing fireline on the perimeters. Up until now, a very, very small percentage of the edges of the fires have containment line.

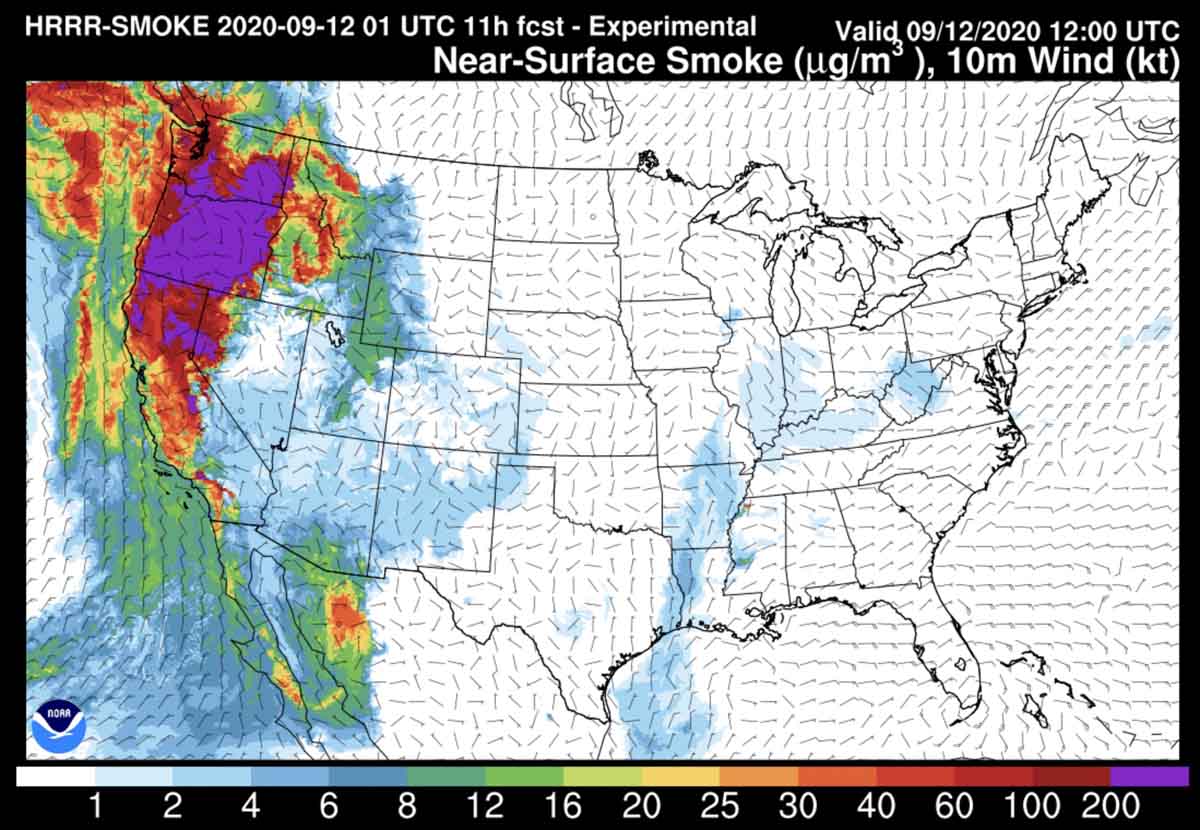

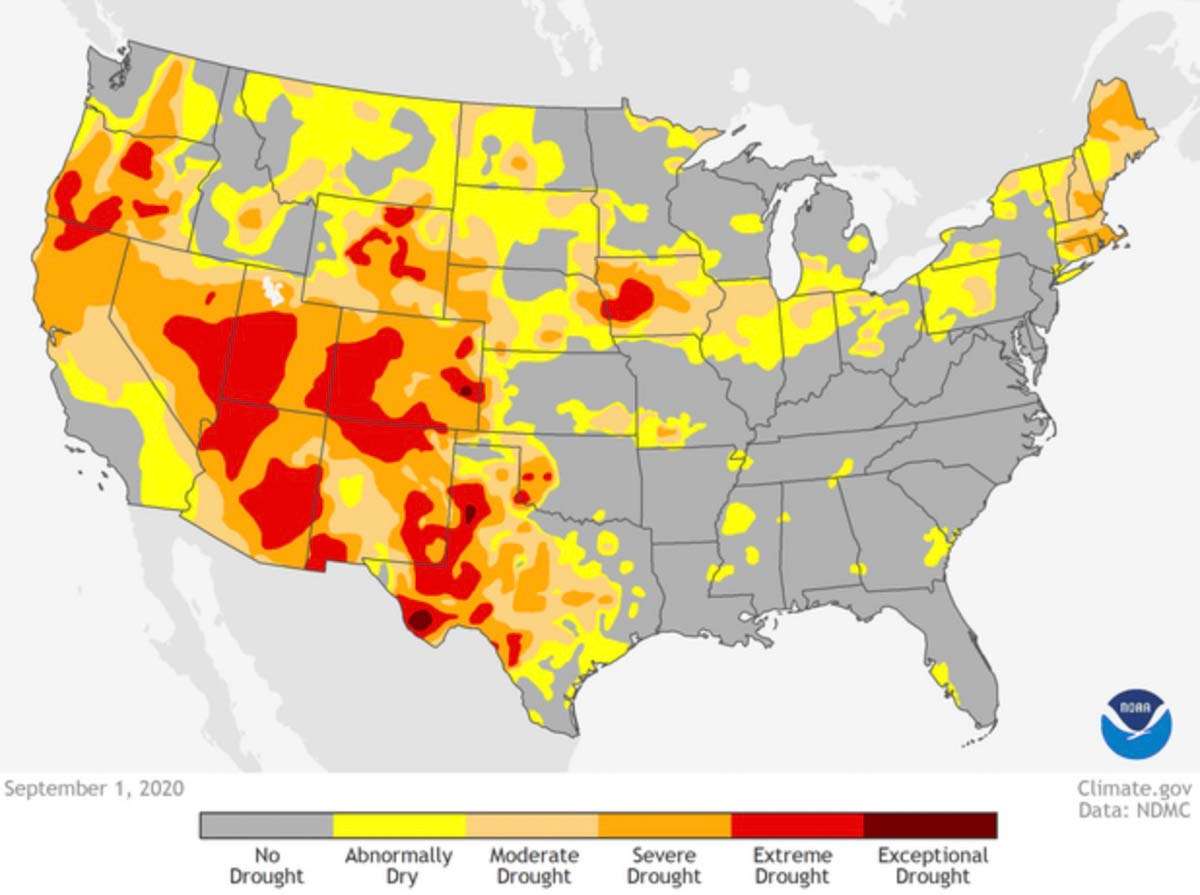

Doug Grafe, chief of fire protection at the Oregon Department of Forestry, said eight of the large fires “will be on our landscape until the winter rains fall. Those fires represent close to 1 million acres … We will see smoke and we will have firefighters on those fires up until the heavy rains.”

Three Area Command Teams (ACT) were mobilized Thursday to assist local units in suppressing the fires in the western states. One of them, led by Area Commander Joe Stutler, will be coordinating the efforts in northwest Oregon. The other two will be California.

Typically an ACT is used to oversee the management of large incidents or those to which multiple Incident Management Teams have been assigned. They can take some of the workload off the local administrative unit when they have multiple incidents going at the same time. Your typical Forest or Park is not usually staffed to supervise two or more Incident Management Teams fighting fire in their area. An ACT can provide decision support to Multi-Agency Coordination Groups for allocating scarce resources and help mitigate the span of control for the local Agency Administrator. They also ensure that incidents are properly managed, coordinate team transitions, and evaluate Incident Management Teams.